After a retail strategy is devised and enacted, it must be continuously assessed and necessary adjustments made. A vital evaluation tool is the retail audit, which systematically examines and evaluates a firm’s total retailing effort or a specific aspect of it. The purpose of an audit is to study what a retailer is presently doing, appraise performance, and make recommendations for the future. An audit investigates a retailer’s objectives, strategy, implementation, and organization. Goals are reviewed and evaluated for their clarity, consistency, and appropriateness. The strategy and the methods for deriving it are analyzed. Also, the application of the strategy and how it is received by customers are reviewed. The organizational structure is analyzed with regard to lines of command and other factors.

Good auditing includes these elements: (1) Audits are conducted regularly. (2) In-depth analysis is involved. (3) Data are amassed and analyzed systematically. (4) An open-minded, unbiased perspective is maintained. (5) There is a willingness to uncover weaknesses to be corrected, as well as strengths to be exploited. (6) After an audit is completed, decision makers are responsive to the recommendations made in the audit report.

1. Undertaking an Audit

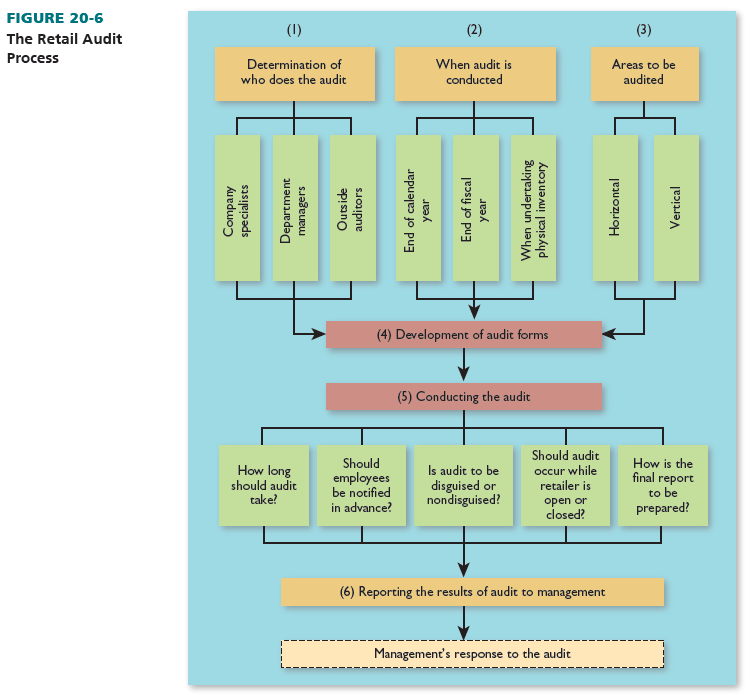

There are six steps in retail auditing. See Figure 20-6 for an overview of the retail auditing process, which is described next: (1) Determine who does an audit. (2) Decide when and how often an audit is done. (3) Establish the areas to be audited. (4) Develop audit form(s). (5) Conduct the audit. (6) Report to management.

DETERMINING WHO DOES THE AUDIT One or a combination of three parties can be involved: a company audit specialist, a company department manager, and/or an outside auditor.

A company audit specialist is an internal employee whose prime responsibility is the retail audit. The advantages of this person include the auditing expertise, thoroughness, level of knowledge about the firm, and ongoing nature (no time lags). Disadvantages include the costs (especially for retailers that do not need full-time auditors) and the auditor’s limited independence.

A company department manager is an internal employee whose prime job is operations management; that manager may also be asked to participate in the retail audit. The advantages are that there are no added personnel expenses and that the manager is knowledgeable about the firm and its operations. Disadvantages include the manager’s time away from the primary job, the potential lack of objectivity, time pressure, and the complexity of companywide audits.

An outside auditor is not a retail employee but a paid consultant. Advantages are the auditor’s experience, objectivity, and thoroughness. Disadvantages are the high costs per day or hour (for some retailers, it may be cheaper to hire per-diem consultants than full-time auditors; the opposite is true for larger firms), the time lag while a consultant gains familiarity with the firm, the failure of some firms to use outside specialists continuously, and some employees’ reluctance to cooperate.

DETERMINING WHEN AND HOW OFTEN THE AUDIT IS CONDUCTED Logical times for auditing are the end of the calendar year, the end of the retailer’s annual reporting year (fiscal year), or when a complete physical inventory is conducted. Each of these is appropriate for evaluating a retailer’s operations during the previous period. An audit must be done at least annually, although some retailers desire more frequent analysis. It is important that the same period(s), such as January-December, be studied to make meaningful comparisons, projections, and adjustments.

DETERMINING AREAS TO BE AUDITED A retail audit typically includes more than financial analysis; it reviews various aspects of a firm’s strategy and operations to identify strengths and weaknesses. There are two types of audits. They should be used in conjunction with one another because a horizontal audit often reveals areas that merit further investigation by a vertical audit.

A horizontal retail audit analyzes a firm’s overall performance, from the organizational mission, to goals, to customer satisfaction, to the basic retail strategy mix and its implementation in an integrated, consistent way. It is also known as a “retail strategy audit.” A vertical retail audit analyzes—in depth—a firm’s performance in one area of the strategy mix or operations, such as the credit function, customer service, merchandise assortment, or interior displays. A vertical audit is focused and specialized.

DEVELOPING AUDIT FORMS To be systematic, a retailer should use detailed audit forms. An audit form lists the area(s) to be studied and guides data collection. It usually resembles a questionnaire and is completed by the auditor. Without audit forms, analysis is more haphazard and subjective. Key questions may be omitted or poorly worded. Auditor biases may appear. Most significantly, questions may differ from one audit period to another, which limits comparisons. Examples of retail audit forms are presented shortly.

CONDUCTING THE AUDIT Next, the audit itself is undertaken. Management specifies how long the audit will take. Prior notification of employees depends on management’s perception of two factors: the need to compile some data in advance to save time versus the desire to get an objective picture and not a distorted one (which may occur if employees have too much notice). With a disguised audit, employees are unaware that it is taking place. It is useful if the auditor investigates an area such as personal selling and acts as a customer to elicit employee responses. With a nondisguised audit, employees know an audit is being conducted. This is desirable if employees are asked specific operational questions and to help in gathering data.

Some audits should be done while the retailer is open, such as assessing parking adequacy, in-store customer traffic patterns, the use of vertical transportation, and customer relations. Others should be done when the firm is closed, such as analyses of the condition of fixtures, inventory levels and turnover, financial statements, and employee records.

An audit report can be formal or informal, brief or long, oral or written, and a statement of findings or a statement of findings plus recommendations. It has a better chance of acceptance if presented in the format desired by management.

REPORTING AUDIT FINDINGS AND RECOMMENDATIONS TO MANAGEMENT The last auditing step is to present findings and recommendations to management. It is the role of management— not the auditor—to see what adjustments (if any) to make. Decision makers must read the report thoroughly, consider each point, and enact the needed strategic changes. They should treat each audit seriously and react accordingly. No matter how well an audit is done, it is not a worthwhile activity if management fails to enact recommendations.

2. Responding to an Audit

After management studies audit findings, appropriate actions are taken. Areas of strength are continued and areas of weakness are revised. The actions must be consistent with the retail strategy and noted in the firm’s retail information system (for further reference).

Retailers with multiple Web sites and/or a large number of brands or stores are dependent on many interconnected processes to ensure optimal customer experience and successful performance. The best way of acting upon the results of retail audits is to tailor actions to local market conditions and demographics, incorporate variations in product assortment as necessary, engage in retail consolidation if appropriate, better handle a new or mature distributor and wholesaler network, and tweak go-to-market approaches if appropriate.18

3. Possible Difficulties in Conducting a Retail Audit

Several obstacles may occur in doing a retail audit. A retailer should be aware of them:

- An audit may be costly.

- It may be quite time consuming.

- Performance measures may be inaccurate.

- Employees may feel threatened and not cooperate as much as desired.

- Incorrect data may be collected.

- Management may not be responsive to the findings.

At present, many retailers—particularly small ones—still do not understand or perform systematic retail audits. But this must change if they are to assess themselves properly and plan correctly for the future.

4. Illustrations of Retail Audit Forms

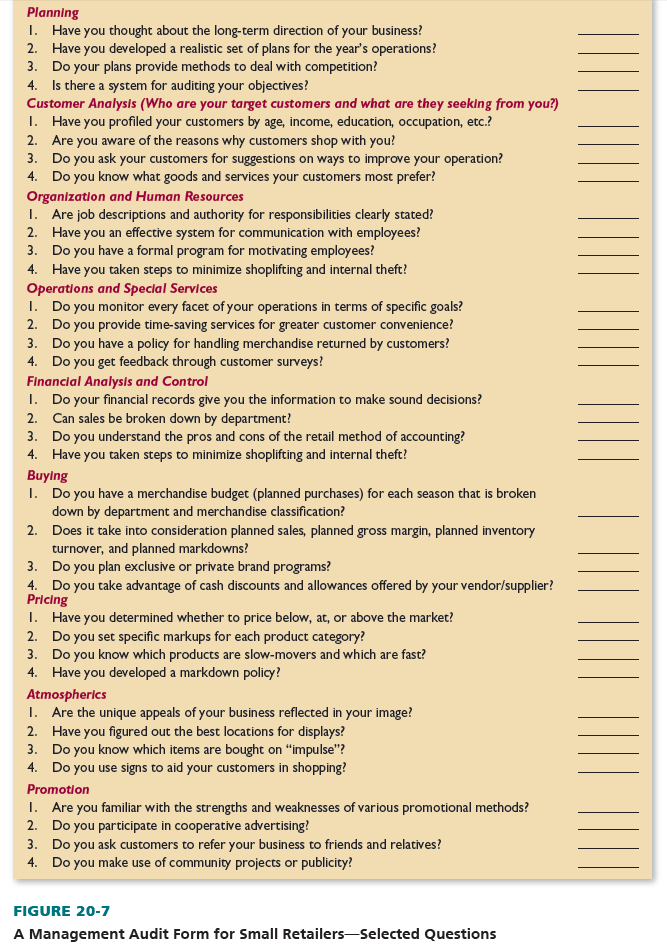

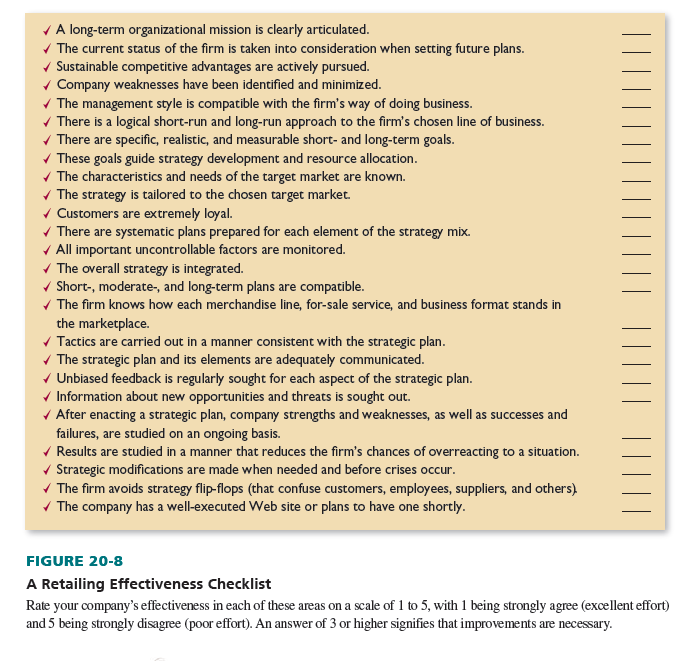

Here, we present a management audit form and a retailing effectiveness checklist to show how small and large retailers can inexpensively, yet efficiently, conduct retail audits. An internal or external auditor (or department manager) could periodically complete one of these forms and then discuss the findings with management. The examples noted are both horizontal audits. A vertical audit would involve an in-depth analysis of any one area in the forms.

A MANAGEMENT AUDIT FORM FOR SMALL RETAILERS Under the auspices of the U.S. Small Business Administration, a Marketing Checklist for Small Retailers was devised. Although written for small firms, it is a comprehensive horizontal audit applicable to all retailers. Figure 20-7 shows selected questions from this audit form. “Yes” is the desired answer to each question. For questions answered negatively, the firm must learn the causes and adjust its strategy.

A RETAILING EFFECTIVENESS CHECKLIST Figure 20-8 has another type of audit form to assess performance and prepare for the future: a retailing effectiveness checklist. It can be used by small and large firms alike. The checklist is more strategic than the Management Audit for Small Retailers—which is more tactical. Unlike the yes-no answers in Figure 20-7, the checklist lets a retailer rate its performance from 1 to 5 in each area; this provides more in-depth information. However, a total score should not be computed (unless items are weighted), because all items are not equally important. A simple summation would not be a meaningful score.

Source: Barry Berman, Joel R Evans, Patrali Chatterjee (2017), Retail Management: A Strategic Approach, Pearson; 13th edition.

28 May 2021

28 May 2021

28 May 2021

28 May 2021

28 May 2021

28 May 2021