Those who launch or found an entrepreneurial venture have an important role to play in shaping the firm’s business model. Stated even more directly, it is widely known that a well-conceived business plan, one that flows from the firm’s previously established business model, cannot get off the ground un- less a firm has the leaders and personnel to carry it out. As some experts put it, “People are the one factor in production … that animates all the others.”3

Often, several start-ups develop what is essentially the same idea at the same time. When this happens, the key to success is not the idea but rather the abil- ity of the initial founder or founders to assemble a team that can execute the idea better than anyone else.

The way a founder builds a new-venture team sends an important signal to potential investors, partners, and employees. Some founders like the feeling of control and are reluctant to involve themselves with partners or hire managers who are more experienced than they are. In contrast, other founders are keenly aware of their own limitations and work hard to find the most experienced peo- ple to bring on board. Similarly, some new firms never form an advisory board, whereas others persuade the most important (and influential) people they can find to provide them with counsel and advice. In general, the way to impress potential investors, partners, and employees is to put together as strong a team as possible.4 Investors and others know that experienced personnel and access to good-quality advice contribute greatly to a new venture’s success.

The elements of a new-venture team are shown in Figure 9.1. It’s important to carefully think through each element. Miscues regarding whether team mem- bers are compatible, whether the team is properly balanced in terms of areas of expertise, and how the permanent members of the team will physically work together can be fatal. Conversely, careful attention in each of these areas can help a firm get off to a good start and provide it an advantage over competitors.

There is a common set of mistakes to avoid when putting together a new- venture team. These mistakes raise red flags when a potential investor, employee, or business partner evaluates a new venture. The most common mistakes are shown in Table 9.1.

In the reminder of this chapter, we examine each element shown in Figure 9.1. While reading these descriptions, remember that entrepreneurial ventures vary in how they use the elements.

1. The founder or founders

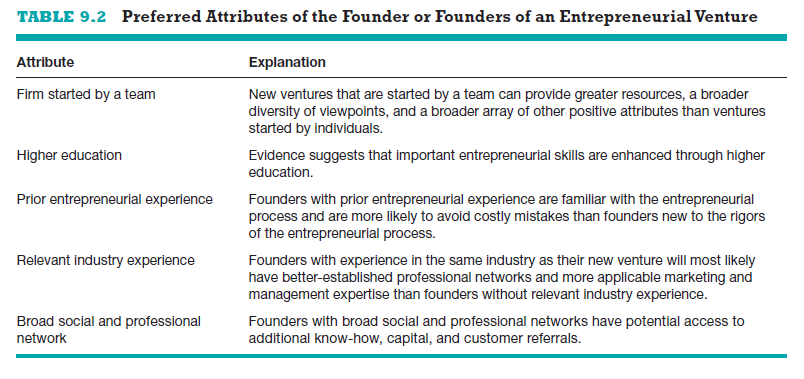

Founders’ characteristics and their early decisions significantly affect the way an entrepreneurial venture is received and the manner in which the new-ven- ture team takes shape. The size of the founding team and the qualities of the founder or founders are the two most important issues in this matter.

Size of the Founding Team The first decision that most founders face is whether to start a firm on their own or whether to build an initial found- ing team. Studies show that 50 to 70 percent of all new firms are started by more than one individual.5 However, experts disagree about whether new ventures started by a team have an advantage over those started by a sole entrepreneur. Teams bring more talent, resources, ideas, and professional contacts to a new venture than does a sole entrepreneur.6 In addition, the psychological support that co-founders of a business can offer one another can be an important element in a new venture’s success.7 Conversely, a lot can go wrong in a partnership—particularly one that’s formed between peo- ple who don’t know each other well. Team members can easily differ in terms of work habits, tolerances for risk, levels of passion for the business, ideas on how the business should be run, and similar key issues.8 If a new-venture team isn’t able to reach consensus on these issues, it may be handicapped from the outset.

When a new venture is started by a team, several issues affect the value of the team. First, teams that have worked together before, as opposed to teams that are working together for the first time, have an edge.9 If people have worked together before and have decided to partner to start a firm together, it usu- ally means that they get along personally and trust one another.10 They also tend to communicate with one another more effectively than people who are new to one another.11 Second, if the members of the team are heterogeneous, meaning that they are diverse in terms of their abilities and experiences, rather than homogeneous, meaning that their areas of expertise are very similar to one another, they are likely to have different points of view about technology, hiring decisions, competitive tactics, and other important activities. Typically, these different points of view generate debate and constructive conflict among the founders, reducing the likelihood that decisions will be made in haste or without the airing of alternative points of view.12 A founding team can be too big, caus- ing communication problems and an increased potential for conflict. The sweet spot is two to three founders. A founding team larger than four people is typi- cally too large to be practical.13

There are three potential pitfalls associated with starting a firm as a team rather than as a sole entrepreneur. First, the team members may not get along. This is the reason investors favor teams consisting of people who have worked to- gether before. It is simply more likely that people who have gotten along with one another in the past will continue to get along in the future. Second, if two or more people start a firm as “equals,” conflicts can arise when the firm needs to estab- lish a formal structure and designate one person as the chief executive officer (CEO). If the firm has investors, the investors will usually weigh in on who should be appointed CEO. In these instances, it is easy for the founder that wasn’t cho- sen as the CEO to feel slighted. This problem is exacerbated if multiple founders are involved and they all stay with the firm. At some point, a hierarchy will have to be developed, and the founders will have to decide who reports to whom. Some of these problems can be avoided by developing a formal organizational chart from the beginning, which spells out the roles of each founder. Finally, as illus- trated in the “What Went Wrong?” feature, if the founders of a firm have similar areas of expertise, it can be problematic. The founders of Devver were both tech- nically oriented, leaving the firm without a leader on the business side.

Qualities of the Founders The second major issue pertaining to the founders of a firm is the qualities they bring to the table. In the previous sev- eral chapters, we described the importance investors and others place on the strength of the firm’s founders and initial management team. One reason the founders are so important is that in the early days of a firm, their knowledge, skills, and experiences are the most valuable resource the firm has. Because of this, new firms are judged largely on their “potential” rather than their current assets or current performance. In most cases, this results in people judging the future prospects of a firm by evaluating the strength of its founders and initial management team.

Several features are thought to be significant to a founder’s success. The level of a founder’s education is important because it’s believed that entrepre- neurial abilities such as search skills, foresight, creativity, and computer skills are enhanced through obtaining a college degree. Similarly, some observers think that higher education equips a founder with important business-related skills, such as math and communications. In addition, specific forms of educa- tion, such as engineering, computer science, management information systems, physics, and biochemistry, provide the recipients of this education an advantage if they start a firm that is related to their area of expertise.14

Prior entrepreneurial experience, relevant industry experience, and net- working are other attributes that strengthen the chances of a founder’s suc- cess. Indeed, the results of research studies somewhat consistently suggest that prior entrepreneurial experience is one of the most consistent pre- dictors of future entrepreneurial performance.15 Because launching a new venture is a complex task, entrepreneurs with prior start-up experience have a distinct advantage. The impact of relevant industry experience on an entrepreneur’s ability to successfully launch and grow a firm has also been studied.16 Entrepreneurs with experience in the same industry as their cur- rent venture will have a more mature network of industry contacts and will have a better understanding of the subtleties of their respective industries.17

The importance of this factor is particularly evident for entrepreneurs who start firms in technical industries such as biotechnology. The demands of biotechnology are sufficiently intense that it would be virtually impossible for someone to start a biotech firm while at the same time learning biotechnology. The person must have an understanding of biotechnology prior to launching a firm through either relevant industry experience or an academic background. Some entrepreneurs, who come from a nonbusiness background, fear that a lack of business experience will be their Achilles’ heel. There are several steps, techniques, or approaches to business that entrepreneurs can utilize to overcome a lack of business experience. These steps and approaches are highlighted in the “Savvy Entrepreneurial Firm” feature.

A particularly important attribute for founders or founding teams is the presence of a mature network of social and professional contacts.18 Founders must often “work” their social and personal networks to raise money or gain access to critical resources on behalf of their firms.19 Networking is building and maintaining relationships with people whose interests are similar or whose relationship could bring advantages to a firm. The way this might play out in practice is that a founder calls a business acquaintance or friend to ask for an introduction to a potential investor, business partner, or customer. For some founders, networking is easy and is an important part of their daily routine. For others, it is a learned skill.

Table 9.2 shows the preferred attributes of a firm’s founder or founders. Start-ups that have founders or a team of founders with these attributes have the best chances of early success. If an individual is starting a company and is looking for a co-founder, there are several websites dedicated to matchmak- ing co-founders for start-ups. Two of the best sites are CofoundersLab (www. cofounderslab.com) and Founder2Be (www.founder2be.com).

2. The management team and key employees

Once the decision to launch a new venture has been made, building a man- agement team and hiring key employees begins. Start-ups vary in terms of how quickly they need to add personnel. In some instances, the founders work alone for a period of time while the business plan is being written and the venture begins taking shape. In other instances, employees are hired immediately.

One technique available to entrepreneurs to help prioritize their hiring needs is to maintain a skills profile. A skills profile is a chart that depicts the most important skills that are needed and where skills gaps exist. A skills profile for New Venture Fitness Drinks, the fictitious company introduced in Chapter 3, is shown in Figure 9.2. Along with depicting where a firm’s most important skills gaps exist, a skills profile should explain how current skills gaps are being dealt with. For example, two of New Venture Fitness Drink’s skills gaps are being covered (on a short-term basis) by members of the board of advisors and the third skills gap does not need to be filled until the firm initiates a franchising program, which is still three to five years in the future.

Evidence suggests that finding good employees (and certainly good key em- ployees) today is not an easy task. According to a 2013 Wells Fargo/Gallop Small Business Index Survey, when it comes to finding qualified employees, 53 percent of small business owners said it is very difficult to do so, 30 percent said it is difficult, and 23 percent said it is somewhat difficult.20 Similarly, a 2011 sur-vey conducted by the University of Maryland’s School of Business and Network Solutions asked small business owners how well they competed with larger com- panies for good employees; only 46 percent said they were successful with these efforts. Respondents also said that recruiting workers who were comfortable in a small business setting is difficult.21

To save money, increase flexibility, and mitigate the difficulty in finding good employees, new ventures use four different sources of labor to get their work done. These are shown in Table 9.3. The first is employees. An employee is someone who works for a business, at the business’s location or virtually, utilizing the business’s tools and equipment and according to the business’s policies and procedures.22 These rules can vary somewhat, particularly as it pertains to working at the business’s location. Most businesses bring on employees fairly slowly because of the costs involved. While employees are valuable, they are expensive. An employee who makes $50,000 a year costs a business more than $50,000 a year. Along with an employee’s base salary, the employer pays a portion of the employee’s Social Security (FICA) and Medicare taxes, provides workers’ compensation insurance, pays into an unemployment fund, and provides benefits (such as health insurance and paid vacation) if benefits are part of the job. A general rule of thumb for an employer that offers benefits is that the benefits and taxes cost 33 percent of the base pay. As a result, a $50,000 per year employee would cost the business $66,500 per year.

The second resource that businesses utilize to get their work done is interns. An intern is a person who works for a business as an apprentice or trainee for the purpose of obtaining practical experience. For example, TOMS (the focal firm in Case 4.2), used many interns in getting its business up and running and still relies heavily on interns today. Many tech companies, in particular, have formal internship programs. Facebook runs a 12-week internship program (this pro- gram is described at www.facebook.com/careers/university). Google sponsors a variety of internship programs, which are detailed at www.google.com/about/ careers/students. Many firms run internship programs not only to utilize the help, but as a recruiting tool. It provides them a chance to “look” at a potential hire before making a formal commitment to that person. Many companies also enjoy having interns around because of their vigor, enthusiasm, and tech-savvy skills. For example, a start-up founded by two 50-year-old individuals may learn a lot from college-aged interns about how to use social media platforms such as Facebook and Twitter more effectively in their business.

The third resource that firms utilize to get their work done is freelancers (also called contractors). A freelancer is a person who is in business for themselves, works on their own time with their own tools and equipment, and performs ser- vices for a number of different clients.23 For example, a business may hire a free-

lancer to manage the search engine optimization (SEO) for its website, and pay the freelancer an hourly or monthly fee. Businesses typically find freelancers via word of mouth or through websites such as Odesk or Elance. Odesk and Elance, as explained in the “Partnering for Success” feature in Chapter 4, specialize in matching freelancers with businesses that are looking for specific types of help.

The fourth resource that businesses draw upon to complete their work is virtual assistants. A virtual assistant is a freelancer who provides adminis- trative, technical, or creative assistance to clients remotely from a home office.

Businesses use virtual assistants for everything from making customer service calls, to data entry in accounting or bookkeeping platforms, to sending out thank you notes to clients. Similar to freelancers, virtual assistants can be lo- cated on online platforms like Odesk and Elance. As of June 2014, Odesk.com had over 17,000 virtual assistants listed that were looking for additional work.

An advantage businesses have in using freelancers and virtual assistants is that they are considered to be “independent contractors.” As a result, a business is not responsible for costs (such as Social Security and Medicare taxes, work- ers’ compensation insurance, paying into an unemployment fund, and benefits) beyond their hourly or contracted pay. Businesses have to be careful, however, to not incorrectly categorize an employee as an independent contractor to save money on taxes and benefits. The IRS looks closely at the distinction and can levy severe penalties if workers are misclassified.

Many founders worry about hiring the wrong person for a key role, regard- less of whether the person is an employee, an intern, a freelancer, or a virtual assistant. Because most new firms are strapped for cash, everyone who is hired must make a valuable contribution. It’s not good enough to hire someone who is well intended but who doesn’t precisely fit the job. On some occasions, key hires work out perfectly and fill the exact roles that a firm’s founders need. For example, Dave Olsen was one of the first employees hired by Starbucks founder Howard Schultz. At the time of his hiring, Olsen was the owner of a popular coffeehouse in the university district of Seattle, the city where Starbucks was launched. In his autobiography, Schultz recalls the following about the hiring of Olsen:

On the day of our meeting, Dave and I sat on my office floor and I started spread- ing the plans and blueprints out and talking about my idea. Dave got it right away. He had spent ten years in an apron, behind a counter, serving espresso drinks. He had experienced firsthand the excitement people can develop about espresso, both in his café and in Italy. I didn’t have to convince him that this idea had big potential. He just knew it in his bones. The synergy was too good to be true. My strength was looking outward: communicating the vision, inspiring investors, raising money, finding real estate, designing the stores, building the brand, and planning for the future. Dave understood the inner workings: the nuts and bolts of operating a retail café, hiring and training baristas (coffee brewers), ensuring the best quality coffee.24

The fear that an employee will not work out as well as Dave Olsen did for Starbucks is one of the attractions for hiring interns, freelancers, and virtual assistants. These individuals work on strictly an “as needed” basis, or on fairly short-term contracts, and a business can simply move on if the person doesn’t work out. In contrast, separating from a full-time or even a part-time employee can be much more difficult.

2. The roles of the Board of Directors

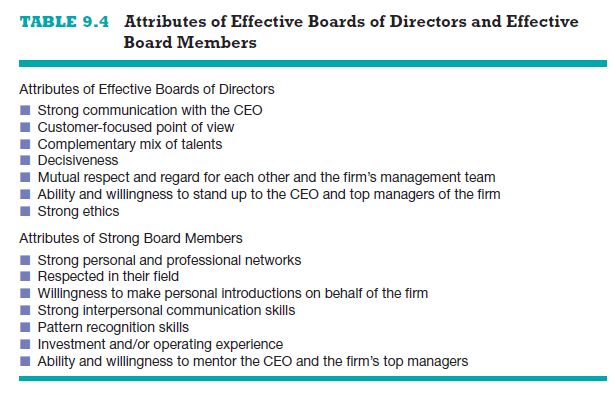

If a new venture organizes as a corporation, it is legally required to have a board of directors—a panel of individuals who are elected by a corporation’s shareholders to oversee the management of the firm.25 A board is typically made up of both inside and outside directors. An inside director is a person who is also an officer of the firm. An outside director is someone who is not employed by the firm. A board of directors has three formal responsibilities: (1) appoint the firm’s officers (the key managers), (2) declare dividends, and (3) oversee the affairs of the corporation. In the wake of corporate scandals such as Enron, WorldCom, and others, there is a strong emphasis on the board’s role in making sure the firm is operating ethically. One outcome of this move- ment is a trend toward putting more outsiders on boards of directors, because people who do not work for the firm are usually more willing to scrutinize the behavior of management than insiders who work for the company. Most boards meet formally three or four times a year. Large firms pay their directors for their service. New ventures are more likely to pay their directors in company stock or ask them to serve without direct compensation—at least until the company is profitable. The boards for publicly traded companies are required by law to have audit and compensation committees. Many boards also have nominating committees to select stockholders to run for vacant board positions. A list of the most desirable qualities in a board of directors and the most desirable qualities in individual board members is provided in Table 9.4.

If handled properly, a company’s board of directors can be an important part of the new-venture team.26 Providing expert guidance and legitimacy in the eyes of others (e.g., customers, investors, and even competitors) are two ways a board of directors can help a new firm get off to a good start and develop what, it is hoped, will become a sustainable competitive advantage.

Provide expert guidance Although a board of directors has formal gov- ernance responsibilities, its most useful role is to provide guidance and sup- port to the firm’s managers.27 Many CEOs interact with their board members frequently and obtain important input. The key to making this happen is to pick board members with needed skills and useful experiences who are willing to give advice and ask insightful and probing questions. The extent to which an effective board can help shape a firm and provide it a competitive advan- tage in the marketplace is expressed by Ram Charan, an expert on the role of boards of directors in corporations:

They (effective boards) listen, probe, debate, and become engaged in the com- pany’s most pressing issues. Directors share their expertise and wisdom as a mat- ter of course. As they do, management and the board learn together, a collective wisdom emerges, and managerial judgment improves. The on-site coaching and consulting expand the mental capacity of the CEO and the top management team and give the company a competitive edge out there in the marketplace.28

Because managers rely on board members for counsel and advice, the search for outside directors should be purposeful, with the objective of filling gaps in the experience and background of the venture’s executives and the other directors. For example, if two computer programmers started a software firm and neither one of them had any marketing experience, it would make sense to place a marketing executive on the board of directors. Indeed, a board of direc- tors has the foundation to effectively serve its organization when its members represent many important organizational skills (e.g., manufacturing, human resource management, and financing) involved with running a company.

Lend legitimacy Providing legitimacy for the entrepreneurial venture is an- other important function of a board of directors. Well-known and respected board members bring instant credibility to the firm. For example, just imagine the posi- tive buzz a firm could generate if it could say that Blake Mycoskie of TOMS or Drew Houston of Dropbox had agreed to serve on its board of directors. This phe- nomenon is referred to as signaling. Without a credible signal, it is difficult for potential customers, investors, or employees to identify high-quality start-ups. Presumably, high-quality individuals would be reluctant to serve on the board of a low-quality firm because that would put their reputation at risk. So when a high-quality individual does agree to serve on a firm’s board, the individual is in essence “signaling” that the company has potential to be successful.29

Achieving legitimacy through high-quality board members can result in other positive outcomes. Investors like to see new-venture teams, including the board of directors, that have people with enough clout to get their foot in the door with potential suppliers and customers. Board members are also often instrumental in helping young firms arrange financing or funding. As we will discuss in Chapter 10, it’s almost impossible for an entrepreneurial venture’s founders to get an investor’s attention without a personal introduction. One way firms deal with this challenge is by placing individuals on their boards that are acquainted with people in the investment community.

Potbelly, which is a restaurant chain that specializes in low-cost sandwiches, cookies, and shakes, is an example of a company with a well-designed board of directors. Its nine-member board consists of two inside directors and seven outsiders. The board members are listed below. Note that the outside members include individuals with backgrounds in real estate, restaurant chain devel- opment, hospitality management, finance, and consumer products. Potbelly, which launched an IPO in 2013 and has aggressive growth plans, will benefit from guidance in each of the areas the different board members represent.30

- Aylwin lewis CEo and President of Potbelly

- Bryant Keil Founding Chairman of Potbelly; 2007 Ernst & Young Entrepreneur of the Year Award Recipient

- Vann Avedisian President of Highgate Holdings, a fully-integrated real estate investment firm

- Peter Bassi Retired Chairman of Yum! Restaurants International

- Susan Chapman-Hughes Senior Vice President of American Express

- Gerald Gallagher Venture Capitalist, oak Investment Partners

- Maria Gottschalk CEo of Pampered Chief

- Dan levitan Venture Capitalist and Cofounder of Maveron llC, a VC firm that invests strictly in consumer companies

- Dan Ginsberg CEo of Dermalogica, a U.S.-based skincare brand

Source: Barringer Bruce R, Ireland R Duane (2015), Entrepreneurship: successfully launching new ventures, Pearson; 5th edition.

Its like you read my thoughts! You seem to grasp a lot about this, such as you wrote the e-book in it or something. I think that you just can do with a few p.c. to drive the message house a bit, but instead of that, this is great blog. An excellent read. I will definitely be back.

I?¦ve read several just right stuff here. Certainly value bookmarking for revisiting. I surprise how so much effort you place to create this type of excellent informative web site.