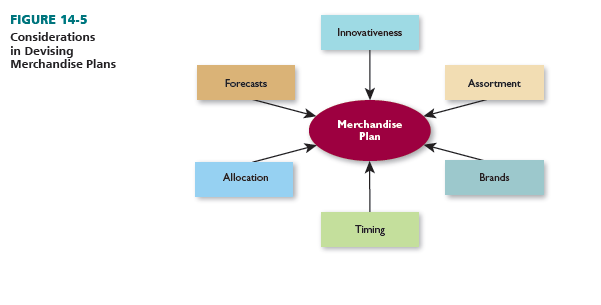

There are several factors to consider in devising merchandise plans, as discussed next. See Figure 14-5.

1. Forecasts

Forecasts are projections of expected retail sales for given periods. They are the foundation of merchandise plans and include overall company projections, product category projections, item- by-item projections, and store-by-store projections (if a chain). Consider L.L. Bean, a privately held apparel and outdoor retailer located in Freeport, Maine. L.L. Bean’s reputation for outstanding customer service and speed of delivery for more than 140,000 products in various sizes, colors, and textures—some unchanged since 1928, others redesigned each year—is an important goal but a formidable task to achieve. Every year, L.L. Bean faces the strategic challenge of inventory and demand forecasting to invest in the right products for the coming year for its multiple channels worldwide. These include catalogs (50 different versions in every U.S. state and in 170 countries); retail stores (28 stores and 10 outlets in the United States, 23 stores and outlets in Japan); Web sites (in 200 countries); Outdoor Adventures Programs (more than 150,000 U.S. customers); and corporate sales. L.L. Bean uses JDA Software’s supply and demand optimization solutions, JDA Demand, to get a read on market trends and develop scalable, integrated multiyear plans for product design, assortment planning, logistics, and enterprise planning.

In this section, forecasting is examined from a general planning perspective. In Chapter 16, the financial dimensions of forecasting are reviewed. When preparing forecasts, it is essential to distinguish among different types of merchandise. Staple merchandise consists of the regular products carried by a retailer. For a supermarket, staples include milk, bread, canned soup, and facial tissues. For a department store, staples include everyday watches, jeans, glassware, and housewares. Because these items have relatively stable sales (sometimes seasonal) and their nature may not change much over time, a retailer can clearly outline the quantities for these items. A basic stock list specifies the inventory level, color, brand, style category, size, package, and so on for every staple item carried by the retailer.

Assortment merchandise consists of apparel, furniture, autos, and other products for which the retailer must carry a variety of products in order to give customers a proper selection. These goods are harder to forecast than staples due to demand variations, style changes, and the number of sizes and colors carried. Decisions are two-pronged: (1) Product lines, styles, designs, and colors are projected. (2) A model stock plan is used to project specific items, such as the number of green, red, and blue pullover sweaters of a certain design by size. With a model stock plan, many items are ordered for popular sizes and colors, and small amounts of less popular sizes and colors fill out the assortment.

Fashion merchandise consists of products that may have cyclical sales due to changing tastes and lifestyles. For these items, forecasting can be hard because styles may change from year to year. “Hot” colors often change back and forth. Seasonal merchandise consists of products that sell well over nonconsecutive time periods. Items such as ski equipment and air-conditioner servicing have excellent sales during one season per year. Because the strongest sales of seasonal items usually occur at the same time each year, forecasting is straightforward.

With fad merchandise, high sales are generated for a short time. Often, toys and games are fads, such as Star Wars toys that flew off store shelves each time a related movie was released. It is hard to forecast whether such products will reach specific sales targets and how long they will be popular. Sometimes, fads turn into extended fads—and sales continue for a long period at a fraction of earlier sales. Trivial Pursuit board games are in the extended fad category.

In forecasting for best-sellers, many retailers use a never-out list to determine the amount of merchandise to purchase for resale. The goal is to purchase enough of these products so they are always in stock. Products are added to and deleted from the list as their popularity changes. Before a new James Patterson novel is released, stores order large quantities to be sure they meet anticipated demand. After it disappears from best-seller lists, smaller quantities are kept. It is a good strategy to use a combination of a basic stock list, a model stock plan, and a never-out list. These lists may overlap.

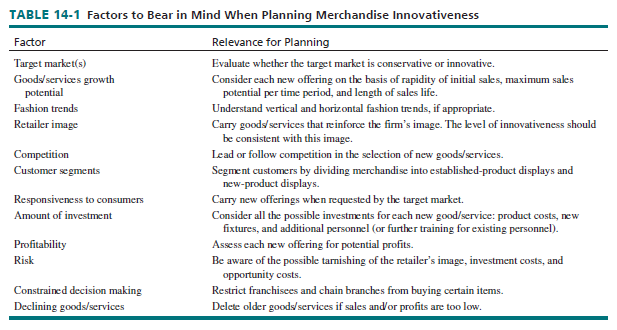

2. Innovativeness

The innovativeness of a merchandise plan depends on a number of factors. See Table 14-1. An innovative retailer has a great opportunity—distinctiveness (by being first to market) and a great risk (possibly misreading customers and being stuck with large inventories). By assessing each factor in Table 14-1 and preparing a detailed plan for merchandising new goods and services, a firm can better capitalize on opportunities and reduce risks. As shown in Figure 14-6, some apparel retailers take innovativeness quite seriously—so do firms such as Brookstone and 7-Eleven:

- Brookstone offers an eclectic mix of unique, functional, and distinctive consumer products— ranging from massage chairs to travel electronics to blood pressure monitors—through catalogs, Web sites, E-mail marketing, and its 200 retail stores in shopping malls, lifestyle centers, and airports. Brookstone provides a fun, interactive shopping experience and an opportunity to discover new and ingenious items where customers are encouraged to try products out for hands-on shopping.

- The convenience store format is quite innovative, as shown by 7-Eleven, which began as Southland Ice Company in 1927, selling milk, eggs, and bread. Today, 7-Eleven introduces new goods and services virtually every week based on the preferences of guests at each locale. Stores vary in size from 2,400 to 3,000 square feet and offer a selection of about 2,500 different goods and services, including food service offerings such as prepared-fresh-daily sandwiches; coffee and its popular Big Gulp fountain soft drink; a wide assortment of fruit, salads, and baked goods; wine; and automated money orders, automatic teller machines, phone cards and, where available, lottery tickets, 24 hours a day, 7 days a week at 7,800 U.S. stores.14

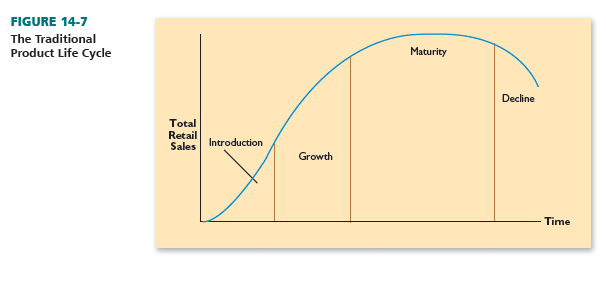

Retailers should assess the growth potential for each new good or service they carry: How fast will a new item generate significant sales? What are the most sales (dollars and units) to be reached in a season or year? Over what period will an item continue selling? One tool to assess potential is the product life cycle, which shows the expected behavior of a good or service over its life. The basic cycle comprises introduction, growth, maturity, and decline stages—shown in Figure 14-7 and described next.

During the introduction stage, a retailer should anticipate a limited target market. The good or service will probably be supplied in one basic version. The manufacturer (supplier) may limit distribution to “finer” stores. Yet, new convenience items such as food and housewares products are normally mass distributed. Items initially distributed selectively tend to have high prices. Mass-distributed products tend to involve low prices to foster faster consumer acceptance. Early promotion must be explanatory, geared to informing shoppers. At this stage, there are few possible suppliers.

As innovators buy a new product and recommend it to friends, sales increase rapidly and the growth stage begins. The target market includes middle-income consumers who are more innovative than average. The assortment expands, as do the retailers carrying a product. Price discounting is not widely used, but competitors offer a range of prices and customer service. Promotion is more persuasive and aimed at acquainting shoppers with availability and services. There are more suppliers.

In the maturity stage, sales reach their maximum, the largest part of the target market is attracted, and shoppers select from broad product offerings. All types of retailers (discount to upscale) carry a good or service in some form. Prestige retailers stress brand names and customer service, while others use active price competition. Price is more often cited in ads. Competition is intense.

Decline is brought on by a shrinking market (due to product obsolescence, newer substitutes, and boredom) and lower profit margins. The target market may be the lowest-income consumers and laggards. Some retailers cut back on the assortment; others drop the good or service. For retailers still carrying the items, promotion is reduced and geared to price. There are fewer suppliers.

Many retailers pay a lot of attention to new-product additions but not enough to decide whether to drop existing items. Yet, because of limited resources and shelf space, some items have to be dropped when others are added. Instead of intuitively pruning products, a retailer should use structured guidelines:

- Select items for possible elimination on the basis of declining sales, prices, and profits, as well as the appearance of substitutes.

- Gather and analyze detailed financial and other data about these items.

- Consider nondeletion strategies such as cutting costs, revising promotion efforts, adjusting prices, and cooperating with other retailers.

- After making a deletion decision, do not overlook timing, parts and servicing, inventory, and holdover demand.

Sometimes, a seemingly obsolete good or service can be revived. An innovative retailer recognizes the potential in this area and merchandises accordingly. Direct marketers heavily promote “greatest hits” recordings featuring individual music artists and compilations of multiple artists.

Apparel retailers must be familiar with fashion trends. A vertical trend occurs when a fashion is first introduced to and accepted by upscale consumers and then undergoes changes in its basic form before it is sold to the general public. This type of fashion goes through three stages: (1) distinctive—original designs, designer stores, custom-made, worn by upscale shoppers; (2) emulation—modification of original designs, finer stores, alterations, worn by middle class; and (3) economic emulation—simple copies, discount stores, mass-produced, mass-marketed.

With a horizontal trend, a new fashion is marketed to a broad spectrum of people at its introduction while retaining its basic form. In any social class, there are innovative customers who are opinion leaders. New fashions must be accepted by them, who then convince other members of the same social class (who are more conservative) to buy the items. Fashion is sold across the class and not from one class to another. Figure 14-8 has a checklist for predicting fashion adoption.

3. Assortment

An assortment is the selection of merchandise a retailer carries. It includes both the breadth of product categories and the variety within each category.

A firm first chooses merchandise quality. Should it carry top-line, expensive items and sell to upper-income customers? Or should it carry middle-of-the-line, moderately priced items and cater to middle-income customers? Or should it carry lesser-quality, inexpensive items and attract lower-income customers? Or should it try to draw more than one segment by offering a variety, such as middle- and top-line items? The firm must also decide whether to carry promotional products (low-priced closeout items or special buys used to generate store traffic). Several factors must be reviewed in choosing merchandise quality. See Table 14-2.

Dollar Tree is the largest single-price-point ($1.00) retailer in North America. Its overall visual merchandising strategy encourages a “treasure hunt” orientation to shopping with a selection of high-value, low-cost merchandise in attractively designed stores that are conveniently located. Dollar Tree provides a balanced selection of everyday consumables such as candy and food, health and beauty care; basic consumables such as paper products and household chemicals; variety merchandise such as toys, stationery, gifts, party goods, greeting cards, an soft goods; seasonal (Valentine’s Day, Easter, Halloween, and Christmas merchandise); and closeout and promotional merchandise all for $1 each! Consumables and variety goods each account for 45 percent of merchandise. Consumables encourage frequent store return visits and increase traffic and sales.

After deciding on product quality, a retailer determines its width and depth of assortment. Width of assortment refers to the number of distinct goods/services categories (product lines) a retailer carries. Depth of assortment refers to the variety in any one goods/services category (product line) a retailer carries. As noted in Chapter 5, an assortment can range from wide and deep (department store) to narrow and shallow (box store). Figure 14-9 shows advantages and disadvantages for each basic strategy.

Assortment strategies vary widely. Web retailer Discount Art (www.discountart.com) says it is geared to “the artist who demands good-quality art materials, but also appreciates good prices.” But even small retailers with a narrow product assortment, like the one in Figure 14-10, need a good selection to draw shoppers. KFC’s thousands of worldwide outlets emphasize chicken and related products. They do not sell hamburgers, pizza, or many other popular fast-food items. Macy’s department stores feature thousands of general merchandise items, and Amazon.com is an online department store with millions of items for sale. This is the dilemma that retailers may face in determining how big an assortment to carry. Creating the right merchandise assortment that is frequently refreshed, accurately tailored to local market and E-commerce customer preferences, and seasonal market demand is essential to maximizing ROI and growing top-line sales.16

Retailers should take several factors into account in planning their assortment: If variety is increased, will overall sales go up? Will overall profits? How much space is required for each product category? How much space is available? Carrying 10 varieties of cat food will not necessarily yield greater sales or profits than stocking 4 varieties. The retailer must look at the investment costs that occur with a large variety. Because selling space is limited, it should be allocated to those goods and services generating the most customer traffic and sales. The inventory turnover rate should also be studied.

A distinction should be made among scrambled merchandising, complementary goods and services, and substitute goods and services. With scrambled merchandising, a retailer adds unrelated items to generate more revenues and lift profit margins (such as a florist carrying umbrellas). Handling complementary goods and services lets the retailer sell both basic items and related offerings (such as stereos and CDs) via cross-merchandising. Although scrambled merchandising and cross-merchandising both increase overall sales, carrying too many substitute goods and services (such as competing brands of toothpaste) may shift sales from one brand to another and have little impact on overall retail sales.

These factors are also key as a retailer considers a wider, deeper assortment: (1) Risks, merchandise investments, damages, and obsolescence may rise dramatically. (2) Personnel may be spread too thinly over dissimilar products. (3) Both the positive and negative ramifications of scrambled merchandising may occur. (4) Inventory control may be difficult; overall turnover probably will slow down.

A retailer may not have a choice about stocking a full assortment within a product line if a powerful supplier insists that the retailer carry its entire line or it will not sell at all to that retailer. But large retailers—and smaller ones belonging to cooperative buying groups—are now standing up to suppliers, and many retailers stock their own brands next to those of the manufacturer.

4. Brands

As part of its assortment planning, a retailer chooses the proper mix of manufacturer, private, and generic brands—a challenge made more complex with the proliferation of brands. Manufacturer (national) brands are produced and controlled by manufacturers. They are usually well known, are supported by manufacturer ads, are somewhat pre-sold to consumers, require limited retailer investment in marketing, and often represent maximum quality to consumers.

Manufacturer brands dominate sales in many categories. Popular manufacturer brands include Apple, Coke, Gillette, Levi’s, Microsoft, Nike, Revlon, and Samsung. The retailers likely to rely most heavily on manufacturer brands are small firms, Web firms, discounters, and others that want the credibility associated with well-known brands or that have low-price strategies (so consumers can compare the prices of different retailers on name-brand items). Although they face extensive competition from private brands, manufacturer brands remain the dominant type of brand, accounting for more than 80 percent of all retail sales worldwide.17 See Figure 14-11.

Private (dealer or store) brands contain names designated by wholesalers or retailers. They are more profitable to retailers, are better controlled by retailers, are not sold by competing retailers, are less expensive for consumers, and lead to customer loyalty to retailers. With most private brands, retailers must line up suppliers, arrange for distribution and warehousing, sponsor ads, create displays, and absorb losses from unsold items. This is why retailer interest in private brands is growing:

- In dollar sales, private brands account for about 17 percent of U.S. retail revenues; they account for 20 percent of unit sales for consumer packaged goods.18 In Europe, the dollar sales figure for private brands at grocery stores ranges from 17 percent of retail store revenues in Italy to 53 percent in Switzerland.19

- Private brands are often priced 20 to 30 percent below manufacturer brands. This benefits consumers and retailers (whose costs are lower and whose revenues are shared by fewer parties). In general, gross profits are higher for private brands than manufacturer brands, despite their lower prices.

- At Gap, Old Navy, Limited, Uniqlo, McDonald’s, Aldi, Trader Joe’s, and many other retailers, private brands represent most or all of company revenues.

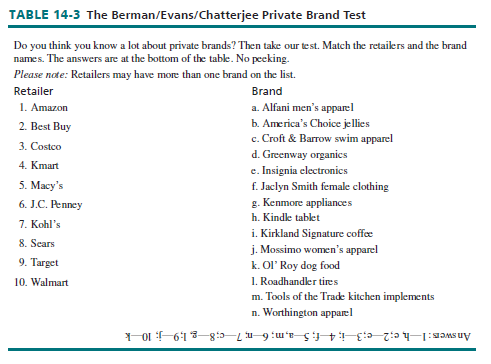

- At virtually all large retailers, both private brands and manufacturer brands are strong. Amazon.com has plans to sell private-label nuts, teas, spices, coffees, baby foods, and vitamins along with millions of manufacturer-branded items. It plans to use such brand names as Happy Belly, Wickedly Prime, Presto!, and Mama Bear for its private-label products and to restrict purchases to its Amazon Prime customers who pay $99 per year for the service.20 Take our private brand challenge in Table 14-3.

In the past, private brands were only discount versions of mid-tier products. Today, shoppers around the world are more conscious of value and increasingly read ingredient labels on products to impute quality. Recognizing that price is not the single differentiator for all shoppers, retailers have invested in developing a wider variety of competitive private-brand offerings. Multitiered private label brands target shoppers at the premium, standard, and value price points. In some categories, differentiated features of the higher-priced premium private label products make them the most expensive and innovative product.21

For example, a premium private brand offered by Harris Teeter (the supermarket chain) is H.T. Traders, which is exclusive to the chain. Harris Teeter applies global food and flavor trends to its premium private-label products such as olive oil and aromatic gourmet coffee to convey superior quality and to cater to consumers who seek quality, novelty, and adventure in their everyday grocery food purchases.22

Care must be taken in deciding how much to emphasize private brands. As previously noted, many consumers are loyal to manufacturer brands and would shop elsewhere if those brands are not stocked or their variety is pruned. See Figure 14-12.

Generic brands feature products’ generic names as brands (such as canned peas); they are a form of private, no-frills goods stocked by some retailers. These items usually get secondary shelf locations, have little or no promotion support, may be of less quality, are stocked in limited assortments, and have plain packages. Retailers control generics and price them well below other brands. In supermarkets, generics account for under 1 percent of sales. For prescription drugs, where the quality of manufacturer brands and generics is similar, generics provide 60 percent of sales.

The competition between manufacturers and retailers for shelf space and profits has led to a battle of the brands, whereby manufacturer, private, and generic brands fight each other for more space and control. Nowhere is this battle clearer than for mature product categories such as paper products at large grocery stores or office products retail chains.23

5. Timing

For new products, the retailer must decide when they are first purchased, displayed, and sold. For established products, the firm must plan the merchandise flow during the year. The retailer should take into account its forecasts and other factors: peak seasons, order and delivery time, routine versus special orders, stock turnover, discounts, and the efficiency of inventory procedures.

Some goods (e.g., winter coats) and services (snow plowing) have peak seasons. These items require large inventories in peak times and less stock during off seasons. Because some people like to shop during off seasons, the retailer should not eliminate the items.

With regard to order and delivery time, how long does it take the retailer to process an order request? After the order is sent to the supplier, how long does it take to receive merchandise? By adding these two periods together, the retailer can get a good idea of the lead time to restock shelves. If it takes a retailer 7 days to process an order and the supplier another 14 days to deliver goods, the retailer should begin a new order at least 21 days before the old inventory runs out.

Routine orders involve restocking staples and other regularly sold items. Deliveries are received weekly, monthly, and so on. Planning and problems are minimized. Special orders involve merchandise not sold regularly, such as custom furniture. They need more planning and cooperation between retailer and supplier. Specific delivery dates are usually arranged.

Stock turnover (how quickly merchandise sells) greatly influences how often items must be ordered. Convenience items such as milk and bread (which are also highly perishable) have a high turnover rate and are restocked quite often. Shopping items such as refrigerators and televisions have a lower turnover rate and are restocked less often.

In deciding when and how often to buy merchandise, the availability of quantity discounts should be considered. Large purchases may result in lower per-unit costs. Efficient inventory procedures, such as electronic data interchange and quick response planning procedures, also decrease costs and order times while raising merchandise productivity.

6. Allocation

The last part of merchandise planning is the allocation of products. A single-unit retailer chooses how much merchandise to place on the sales floor, how much to place in a stockroom, and whether to use a warehouse. A chain also apportions products among stores. Allocation is covered further in Chapter 15.

Some retailers rely on warehouses as distribution centers. Products are shipped from suppliers to these warehouses, and then they are assigned and shipped to individual stores. Other retailers, including many supermarket chains, do not rely as much on warehouses. They have at least some goods shipped directly from suppliers to individual stores.

It is vital for chains, whether engaged in centralized or decentralized merchandising, to have a clear store-by-store allocation plan. Even if merchandise lines are standardized across the chain, store-by-store assortments must reflect the variations in the size and diversity of the customer base, in store size and location, in the climate, and in other factors.

Source: Barry Berman, Joel R Evans, Patrali Chatterjee (2017), Retail Management: A Strategic Approach, Pearson; 13th edition.

I like this blog so much, saved to my bookmarks.