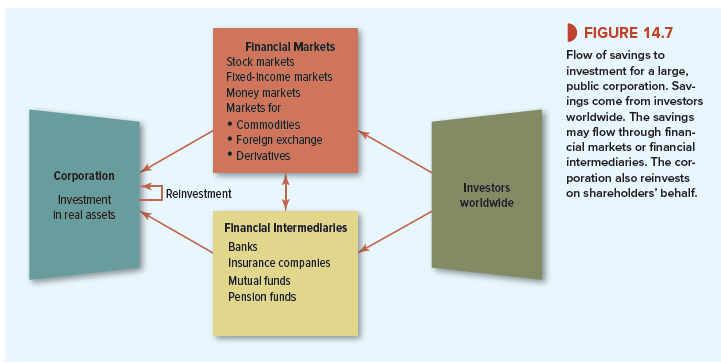

The flow of savings to large public corporations is shown in Figure 14.7. Notice that the savings travel from investors worldwide through financial markets, financial intermediaries, or both. Suppose, for example, that Bank of America raises $300 million by a new issue of shares. An Italian investor buys 6,000 of the new shares for $10 per share. Now Bank of America takes that $60,000, along with money raised by the rest of the issue, and makes a $300 million loan to ExxonMobil. The Italian investor’s savings end up flowing through financial markets (the stock market), to a financial intermediary (Bank of America), and finally to Exxon.

Of course, our Italian friend’s $60,000 doesn’t literally arrive at Exxon in an envelope marked “From L. DaVinci.” Investments by the purchasers of the Bank of America’s stock issue are pooled, not segregated. Sr. DaVinci would own a share of all of Bank of America’s assets, not just one loan to Exxon. Nevertheless, investors’ savings are flowing through the financial markets and then the bank to finance Exxon’s capital investments.

Suppose that another investor decides to open a checking account with Bank of America. The bank can take the money in this checking account and also lend it on to ExxonMobil. In this case, the savings bypass the financial markets and flow directly to a financial intermediary and from there to Exxon.

We now need to flesh out Figure 14.7 by looking at the main financial markets and intermediaries.

1. Financial Markets

A financial market is a market where financial assets are issued and traded. In our example, Bank of America used the financial markets to raise money from investors by a new issue of shares. Such issues are known as primary issues. But in addition to helping companies to raise cash, financial markets also allow investors to trade stocks or bonds among themselves. For example, Mr. Rosencrantz might decide to raise some cash by selling his Bank of America stock at the same time that Mr. Guildenstern invests his savings in the stock. So they make a trade. The result is simply a transfer of ownership from one person to another, which has no effect on the company’s cash, assets, or operations. Such purchases and sales are known as secondary transactions.

Some financial assets have less active secondary markets than others. For example, when a bank lends money to a company, it acquires a financial asset (the company’s promise to repay the loan with interest). Banks do sometimes sell packages of these loans to other banks, but generally they retain the loan until it is repaid by the borrower. Other financial assets are regularly traded. Some, such as shares of stock, are traded on organized exchanges like the New York, London, or Hong Kong stock exchanges. In other cases, there is no organized exchange, and the assets are traded by a network of dealers. Such markets are known as over-the-counter (OTC) markets. For example, in the United States, most government and corporate bonds are traded OTC.

Some financial markets are not used to raise cash but, instead, help firms to manage their risks. In these markets firms can buy or sell derivatives, whose payoffs depend on the prices of other securities or commodities. For example, if a chocolate producer is worried about rising cocoa prices, it can use the derivatives markets to fix the price at which it buys its future cocoa requirements.

2. Financial Intermediaries

A financial intermediary is an organization that raises money from investors and provides financing for individuals, companies, and other organizations. Banks, insurance companies, and investment funds are all intermediaries. These intermediaries are important sources of financing for corporations. They are a stop on the road between savings and real investment.

Why is a financial intermediary different from a manufacturing corporation? First, it may raise money in different ways, for example, by taking deposits or selling insurance policies. Second, it invests that money in financial assets, for example, in stocks, bonds, or loans to businesses or individuals. In contrast, a manufacturing company’s main investments are in plant, equipment, or other real assets.

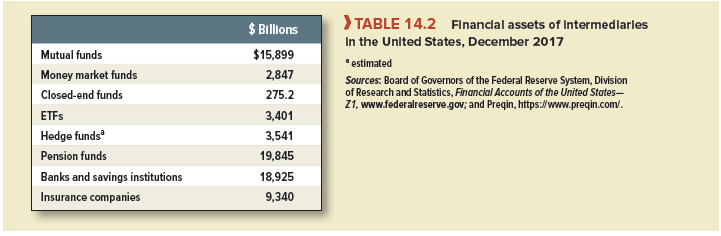

Look at Table 14.2, which shows the financial assets of the different types of intermediaries in the United States. It gives you an idea of the relative importance of different intermediaries. Of course, these assets are not all invested in nonfinancial businesses. For example, banks make loans to individuals as well as to businesses.[1]

3. Investment Funds

We look first at investment funds, such as mutual funds, hedge funds, and pension funds. Mutual funds raise money by selling shares to investors. This money is then pooled and invested in a portfolio of securities.[2] Investors in a mutual fund can increase their stake in the fund’s portfolio by buying additional shares, or they can sell their shares back to the fund if they wish to cash out. The purchase and sale prices depend on the fund’s net asset value (NAV) on the day of purchase or redemption. If there is a net flow of cash into the fund, the manager will use it to buy more stocks or bonds; if there is a net outflow, the fund manager will need to raise the money by selling some of the fund’s investments.

There are just over 8,000 equity and bond mutual funds in the United States. In fact, there are more mutual funds than public companies! The funds pursue a wide variety of investment strategies. Some funds specialize in safe stocks with generous dividend payouts. Some specialize in high-tech growth stocks. Some “balanced” funds offer mixtures of stocks and bonds. Some specialize in particular countries or regions. For example, the Fidelity Investments mutual fund group sponsors funds for Canada, Japan, China, Europe, and Latin America.

Mutual funds offer investors low-cost diversification and professional management. For most investors, it’s more efficient to buy a mutual fund than to assemble a diversified portfolio of stocks and bonds. Most mutual fund managers also try their best to “beat the market”—that is, to generate superior performance by finding the stocks with better-than-average returns. Whether they can pick winners consistently is another question, which we addressed in Chapter 13. In exchange for their services, the fund’s managers take out a management fee. There are also the expenses of running the fund. For mutual funds that invest in stocks, fees and expenses typically add up to nearly 1% per year.

Most mutual funds invest in shares or in a mixture of shares and bonds. However, one particular type of mutual fund, called a money market fund, invests only in short-term safe securities, such as Treasury bills or bank certificates of deposit. Money market funds offer individuals and small- and medium-sized businesses a convenient home in which to park their spare cash. There are nearly 400 money market funds in the United States. Some of these funds are huge. For example, the JPMorgan U.S. Government Money Market Fund had $140 billion in assets in 2017.

Mutual funds are open-end funds—they stand ready to issue new shares and to buy back existing shares. In contrast, a closed-end fund has a fixed number of shares that are traded on an exchange. If you want to invest in a closed-end fund, you cannot buy new shares from the fund; you must buy existing shares from another stockholder in the fund.

If you simply want low-cost diversification, one option is to buy a mutual fund that invests in all the stocks in a stock market index. For example, the Vanguard Index Fund holds all the stocks in the Standard & Poor’s Composite Index. An alternative is to invest in an exchange traded fund, or ETF, which is a portfolio of stocks that can be bought or sold in a single trade. These include Standard & Poor’s Depository Receipts (SPDRs, or “spiders”), which are portfolios matching Standard & Poor’s stock market indexes. You can also buy DIAMONDS, which track the Dow Jones Industrial Average; QUBES or QQQs, which track the Nasdaq 100 index; and Vanguard ETFs that track the U.S. Total Stock Market index, which is a basket of almost all of the stocks traded in the United States. You can also buy ETFs that track foreign stock markets, bonds, or commodities.

ETFs are, in some ways, more efficient than mutual funds. To buy or sell an ETF, you simply make a trade, just as if you bought or sold shares of stock. In this respect, ETFs are like closed-end investment funds. But, with rare exceptions, ETFs do not have managers with the discretion to try to “pick winners.” ETF portfolios are tied down to indexes or fixed baskets of securities. ETF issuers make sure that the ETF price tracks the price of the underlying index or basket.

Like mutual funds, hedge funds also pool the savings of different investors and invest on their behalf. But they differ from mutual funds in at least three ways. First, because hedge funds usually follow complex investment strategies, access is restricted to knowledgeable investors such as pension funds, endowment funds, and wealthy individuals. Don’t try to send a check for $3,000 or $5,000 to a hedge fund; most hedge funds are not in the “retail” investment business. Second, hedge funds are generally established as limited partnerships. The investment manager is the general partner and the investors are the limited partners. Third, hedge funds try to attract the most talented managers by compensating them with potentially lucrative, performance-related fees.[3] In contrast, mutual funds usually charge a fixed percentage of assets under management.

Hedge funds follow many different investment strategies. Some try to make a profit by identifying overvalued stocks or markets that they then sell short. Some hedge funds take bets on firms involved in merger negotiations, others look for mispricing of convertible bonds, and some take positions in currencies and interest rates. “Vulture funds” specialize in the securities of distressed corporations. Hedge funds manage less money than mutual funds, but they sometimes take very big positions and have a large impact on the market.

There are other ways to pool and invest savings. Consider a pension plan set up by a corporation or other organization on behalf of its employees. The most common type of plan is the defined-contribution plan. In this case, a percentage of the employee’s monthly paycheck is contributed to a pension fund. (The employer and employee may each contribute 5%, for example.) Contributions from all participating employees are pooled and invested in securities or mutual funds. (Usually, the employees can choose from a menu of funds with different investment strategies.) Each employee’s balance in the plan grows over the years as contributions continue and investment income accumulates. The balance in the plan can be used to finance living expenses after retirement. The amount available for retirement depends on the accumulated contributions and on the rate of return earned on the investments.[4]

Pension funds are designed for long-run investment. They provide professional management and diversification. They also have an important tax advantage: Contributions are tax-deductible, and investment returns inside the plan are not taxed until cash is finally withdrawn.[5]

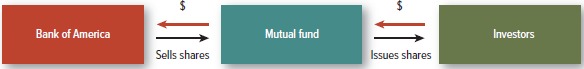

All these investment funds provide a stop on the road from savings to corporate investment. For example, suppose your mutual fund purchases part of that new issue of shares by Bank of America. The orange arrows show the flow of savings to investment:

4. Financial Institutions

Banks and insurance companies are financial institutions.[6] A financial institution is an intermediary that does more than just pool and invest savings. Institutions raise financing in special ways, for example, by accepting deposits or selling insurance policies, and they provide additional financial services. Unlike most investment funds, they not only invest in securities but also lend money directly to individuals, businesses, or other organizations.

Commercial Banks There are just under 5,000 commercial banks in the United States. They vary from giants such as JPMorgan Chase with $2.6 trillion of assets to dwarves like the Emigrant Mercantile Bank with under $4 million.

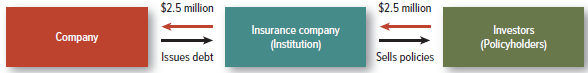

Commercial banks are major sources of loans for corporations. (In the United States, they are generally not allowed to make equity investments in corporations, although banks in most other countries can do so.) Suppose that a local forest products company negotiates a nine- month bank loan for $2.5 million. The flow of savings is

The bank provides debt financing for the company and, at the same time, provides a place for depositors to park their money safely and withdraw it as needed.

We will have plenty more to say about bank loans in Chapter 24.

Investment Banks We have discussed commercial banks, which raise money from depositors and other investors and then make loans to businesses and individuals. Investment banks are different.[7] Investment banks do not take deposits, and they do not usually make loans to companies. Instead, they advise and assist companies in raising financing. For example, investment banks underwrite stock offerings by purchasing the new shares from the issuing company at a negotiated price and reselling the shares to investors. Thus, the issuing company gets a fixed price for the new shares, and the investment bank takes responsibility for distributing the shares to thousands of investors. We discuss share issues in more detail in Chapter 15.

Investment banks also advise on takeovers, mergers, and acquisitions. They offer investment advice and manage investment portfolios for individual and institutional investors. They run trading desks for foreign exchange, commodities, bonds, options, and derivatives.

Investment banks can invest their own money in start-ups and other ventures. For example, the Australian Macquarie Bank has invested in airports, toll highways, electric transmission and generation, and other infrastructure projects around the world.

The largest investment banks are financial powerhouses. They include Goldman Sachs, Morgan Stanley, Lazard, Nomura (Japan), and Macquarie Bank.[8] In addition, the major commercial banks, including Bank of America and Citigroup, all have investment banking operations.[9]

Insurance Companies Insurance companies are more important than banks for the long-term financing of business. They are massive investors in corporate stocks and bonds, and they often make long-term loans directly to corporations.

Suppose a company needs a loan of $2.5 million for nine years, not nine months. It could issue a bond directly to investors, or it could negotiate a nine-year loan with an insurance company:

The money to make the loan comes mainly from the sale of insurance policies. Say you buy a fire insurance policy on your home. You pay cash to the insurance company and get a financial asset (the policy) in exchange. You receive no interest payments on this financial asset, but if a fire does strike, the company is obliged to cover the damages up to the policy limit. This is the return on your investment. (Of course, a fire is a sad and dangerous event that you hope to avoid. But if a fire does occur, you are better off getting a return on your investment in insurance than not having insurance at all.)

The company will issue not just one policy but thousands. Normally the incidence of fires “averages out,” leaving the company with a predictable obligation to its policyholders as a group. Of course the insurance company must charge enough for its policies to cover selling and administrative costs, pay policyholders’ claims, and generate a profit for its stockholders.

It’s really a nice and useful piece of information. I am glad that you shared this helpful information with us. Please keep us up to date like this. Thanks for sharing.