The pecking-order theory starts with asymmetric information—a fancy term indicating that managers know more about their companies’ prospects, risks, and values than do outside investors.

Managers obviously know more than investors. We can prove that by observing stock price changes caused by announcements by managers. For example, when a company announces an increased regular dividend, stock price typically rises because investors interpret the increase as a sign of management’s confidence in future earnings. In other words, the dividend increase transfers information from managers to investors. This can happen only if managers know more in the first place.

Asymmetric information affects the choice between internal and external financing and between new issues of debt and equity securities. This leads to a pecking order, in which investment is financed first with internal funds (reinvested earnings primarily), then by new issues of debt, and finally with new issues of equity. New equity issues are a last resort when the company runs out of debt capacity, that is, when the threat of costs of financial distress brings regular insomnia to existing creditors and to the financial manager.

We will take a closer look at the pecking order in a moment. First, you must appreciate how asymmetric information can force the financial manager to issue debt rather than common stock.

1. Debt and Equity Issues with Asymmetric Information

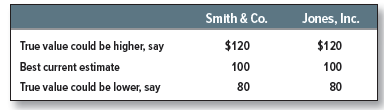

To the outside world, Smith & Company and Jones Inc., our two example companies, are identical. Each runs a successful business with good growth opportunities. The two businesses are risky, however, and investors have learned from experience that current expectations are frequently bettered or disappointed. Current expectations price each company’s stock at $100 per share, but the true values could be higher or lower:

Now suppose that both companies need to raise new money from investors to fund capital investment. They can do this either by issuing bonds or by issuing new shares of common stock. How would the choice be made? One financial manager—we will not tell you which one—might reason as follows:

Sell stock for $100 per share? Ridiculous! It’s worth at least $120. A stock issue now would hand a free gift to new investors. I just wish those skeptical shareholders would appreciate the true value of this company. Our new factories will make us the world’s lowest-cost producer. We’ve painted a rosy picture for the press and security analysts, but it just doesn’t seem to be working. Oh well, the decision is obvious: We’ll issue debt, not underpriced equity. A debt issue will save underwriting fees too.

The other financial manager is in a different mood:

Beefalo burgers were a hit for a while, but it looks like the fad is fading. The fast-food division’s gotta find some good new products or it’s all downhill from here. Export markets are OK for now, but how are we going to compete with those new Siberian ranches? Fortunately the stock price has held up pretty well—we’ve had some good short-run news for the press and security analysts. Now’s the time to issue stock. We have major investments underway, and why add increased debt service to my other worries?

Of course, outside investors can’t read the financial managers’ minds. If they could, one stock might trade at $120 and the other at $80.

Why doesn’t the optimistic financial manager simply educate investors? Then the company could sell stock on fair terms, and there would be no reason to favor debt over equity or vice versa.

This is not so easy. (Note that both companies are issuing upbeat press releases.) Investors can’t be told what to think; they have to be convinced. That takes a detailed layout of the company’s plans and prospects, including the inside scoop on new technology, product design, marketing plans, and so on. Getting this across is expensive for the company and also valuable to its competitors. Why go to the trouble? Investors will learn soon enough, as revenues and earnings evolve. In the meantime the optimistic financial manager can finance growth by issuing debt.

Now suppose there are two press releases:

Jones Inc. will issue $120 million of five-year senior notes.

Smith & Co. announced plans today to issue 1.2 million new shares of common stock. The company expects to raise $120 million.

As a rational investor, you immediately learn two things. First, Jones’s financial manager is optimistic and Smith’s is pessimistic. Second, Smith’s financial manager is also naive to think that investors would pay $100 per share. The attempt to sell stock shows that it must be worth less. Smith might sell stock at $80 per share, but certainly not at $100.[1]

Smart financial managers think this through ahead of time. The end result? Both Smith and Jones end up issuing debt. Jones Inc. issues debt because its financial manager is optimistic and doesn’t want to issue undervalued equity. A smart, but pessimistic, financial manager at Smith issues debt because an attempt to issue equity would force the stock price down and eliminate any advantage from doing so. (Issuing equity also reveals the manager’s pessimism immediately. Most managers prefer to wait. A debt issue lets bad news come out later through other channels.)

The story of Smith and Jones illustrates how asymmetric information favors debt issues over equity issues. If managers are better informed than investors and both groups are rational, then any company that can borrow will do so rather than issuing fresh equity. In other words, debt issues will be higher in the pecking order.

Taken literally, this reasoning seems to rule out any issue of equity. That’s not right because asymmetric information is not always important and there are other forces at work. For example, if Smith had already borrowed heavily, and would risk financial distress by borrowing more, then it would have a good reason to issue common stock. In this case, announcement of a stock issue would not be entirely bad news. The announcement would still depress the stock price—it would highlight managers’ concerns about financial distress—but the fall in price would not necessarily make the issue unwise or infeasible.

High-tech, high-growth companies can also be credible issuers of common stock. Such companies’ assets are mostly intangible, and bankruptcy or financial distress would be especially costly. This calls for conservative financing. The only way to grow rapidly and keep a conservative debt ratio is to issue equity. If investors see equity issued for these reasons, problems of the sort encountered by Smith’s financial manager become much less serious.

With such exceptions noted, asymmetric information can explain the dominance of debt financing over new equity issues, at least for mature public corporations. Debt issues are frequent; equity issues, rare. The bulk of external financing comes from debt, even in the United States, where equity markets are highly information-efficient. Equity issues are even more difficult in countries with less well-developed stock markets.

None of this says that firms ought to strive for high debt ratios—just that it’s better to raise equity by plowing back earnings than issuing stock. In fact, a firm with ample internally generated funds doesn’t have to sell any kind of security and thus avoids issue costs and information problems completely.

2. Implications of the Pecking Order

The pecking-order theory of corporate financing goes like this.

- Firms prefer internal finance.

- They adapt their target dividend payout ratios to their investment opportunities, while trying to avoid sudden changes in dividends.

- Sticky dividend policies, plus unpredictable fluctuations in profitability and investment opportunities, mean that internally generated cash flow is sometimes more than capital expenditures and other times less. If it is more, the firm pays off debt or invests in marketable securities. If it is less, the firm first draws down its cash balance or sells its holdings of marketable securities.

- If external finance is required, firms issue the safest security first. That is, they start with debt, then possibly hybrid securities such as convertible bonds, then perhaps equity as a last resort.

In this theory, there is no well-defined target debt-equity mix because there are two kinds of equity, internal and external, one at the top of the pecking order and one at the bottom. Each firm’s observed debt ratio reflects its cumulative requirements for external finance.

The pecking order explains why the most profitable firms generally borrow less—not because they have low target debt ratios but because they don’t need outside money. Less profitable firms issue debt because they do not have internal funds sufficient for their capital investment programs and because debt financing is first on the pecking order of external financing.

In the pecking-order theory, the attraction of interest tax shields is assumed to be second- order. Debt ratios change when there is an imbalance of internal cash flow, net of dividends, and real investment opportunities. Highly profitable firms with limited investment opportunities work down to low debt ratios. Firms whose investment opportunities outrun internally generated funds are driven to borrow more and more.

This theory explains the inverse intraindustry relationship between profitability and financial leverage. Suppose firms generally invest to keep up with the growth of their industries. Then rates of investment will be similar within an industry. Given sticky dividend payouts, the least profitable firms will have less internal funds and will end up borrowing more.

3. The Trade-Off Theory vs. the Pecking-Order Theory-Some Evidence

In 1995, Rajan and Zingales published a study of debt versus equity choices by large firms in Canada, France, Germany, Italy, Japan, the United Kingdom, and the United States. Rajan and Zingales found that the debt ratios of individual companies seemed to depend on four main factors:[2]

- Size. Large firms tend to have higher debt ratios.

- Tangible assets. Firms with high ratios of fixed assets to total assets have higher debt ratios.

- Profitability. More profitable firms have lower debt ratios.

- Market to book. Firms with higher ratios of market-to-book value have lower debt ratios.

These results convey good news for both the trade-off and pecking-order theories. Trade-off enthusiasts note that large companies with tangible assets are less exposed to costs of financial distress and would be expected to borrow more. They interpret the market-to-book ratio as a measure of growth opportunities and argue that growth companies could face high costs of financial distress and would be expected to borrow less. Pecking-order advocates stress the importance of profitability, arguing that profitable firms use less debt because they can rely on internal financing. They interpret the market-to-book ratio as just another measure of profitability.

It seems that we have two competing theories, and they’re both right! That’s not a comfortable conclusion. So recent research has tried to run horse races between the two theories in order to find the circumstances in which one or the other wins. It seems that the pecking order works best for large, mature firms that have access to public bond markets. These firms rarely issue equity. They prefer internal financing but turn to debt markets if needed to finance investment. Smaller, younger, growth firms are more likely to rely on equity issues when external financing is required.[3]

There is also some evidence that debt ratios incorporate the cumulative effects of market timing.[4] Market timing is an example of behavioral corporate finance. Suppose that investors are sometimes irrationally exuberant (as in the late 1990s) and sometimes irrationally despondent. If the financial manager’s views are more stable than investors’, then he or she can take advantage by issuing shares when the stock price is too high and switching to debt when the price is too low. Thus lucky companies with a history of buoyant stock prices will issue less debt and more shares, ending up with low debt ratios. Unfortunate and unpopular companies will avoid share issues and end up with high debt ratios.

Market timing could explain why companies tend to issue shares after run-ups in stock prices and also why aggregate stock issues are concentrated in bull markets and fall sharply in bear markets.

There are other behavioral explanations for corporate financing policies. For example, Bertrand and Schoar tracked the careers of individual CEOs, CFOs, and other top managers. Their individual “styles” persisted as they moved from firm to firm.[5] For example, older CEOs tended to be more conservative and pushed their firms to lower debt. CEOs with MBA degrees tended to be more aggressive. In general, financial decisions depended not just on the nature of the firm and its economic environment, but also on the personalities of the firm’s top management.

4. The Bright Side and the Dark Side of Financial Slack

Other things equal, it’s better to be at the top of the pecking order than at the bottom. Firms that have worked down the pecking order and need external equity may end up living with excessive debt or passing by good investments because shares can’t be sold at what managers consider a fair price.

In other words, financial slack is valuable. Having financial slack means having cash, marketable securities, readily salable real assets, and ready access to debt markets or to bank financing. Ready access basically requires conservative financing so that potential lenders see the company’s debt as a safe investment.

In the long run, a company’s value rests more on its capital investment and operating decisions than on financing. Therefore, you want to make sure your firm has sufficient financial slack so that financing is quickly available for good investments. Financial slack is most valuable to firms with plenty of positive-NPV growth opportunities. That is another reason why growth companies usually aspire to conservative capital structures.

Of course, financial slack is only valuable if you’re willing to use it. Take a look at the nearby box, which describes how Ford used up all of its financial slack in one enormous debt issue.

There is also a dark side to financial slack. Too much of it may encourage managers to take it easy, expand their perks, or empire-build with cash that should be paid back to stockholders. In other words, slack can make agency problems worse.

Michael Jensen has stressed the tendency of managers with ample free cash flow (or unnecessary financial slack) to plow too much cash into mature businesses or ill-advised acquisitions. “The problem,” Jensen says, “is how to motivate managers to disgorge the cash rather than investing it below the cost of capital or wasting it in organizational inefficiencies.”36

If that’s the problem, then maybe debt is an answer. Scheduled interest and principal payments are contractual obligations of the firm. Debt forces the firm to pay out cash. Perhaps the best debt level would leave just enough cash in the bank, after debt service, to finance all positive-NPV projects, with not a penny left over.

We do not recommend this degree of fine-tuning, but the idea is valid and important. Debt can discipline managers who are tempted to invest too much. It can also provide the pressure to force improvements in operating efficiency. We pick up this theme again in Chapter 32.

5. Is There a Theory of Optimal Capital Structure?

No. That is, there is no one theory that can capture everything that drives thousands of corporations’ debt versus equity choices. Instead, there are several theories, each more or less helpful, depending on each particular corporation’s assets, operations, and circumstances.

In other words, relax: Don’t waste time searching for a magic formula for the optimal debt ratio. Remember too that most value comes from the left side of the balance sheet—that is, from the firm’s operations, assets, and growth opportunities. Financing is less important. Of course, financing can subtract value rapidly if you screw it up, but you won’t do that.

In practice, financing choices depend on the relative importance of the factors discussed in this chapter. In some cases, reducing taxes will be the primary objective. Thus, high debt ratios are found in the lease-financing business (see Chapter 25). Long-term leases are often tax-driven transactions. High debt ratios are also found in developed commercial real estate. For example, modern downtown office buildings can be safe, cash-cow assets if the office space is rented to creditworthy tenants. Bankruptcy costs are small, so it makes sense to lever up and save taxes.

For smaller growth companies, interest tax shields are less important than preserving financial slack. Profitable growth opportunities are valuable only if financing is available when it comes time to invest. Costs of financial distress are high, so it’s no surprise that growth companies try to use mostly equity financing.

There’s another reason why growth companies borrow less. Their growth opportunities are real options, that is, options to invest in real assets. The options contain lots of hidden financial risk. We will see in Chapters 20 through 22 that an option to buy a real asset is equivalent to a claim on a fraction of the asset’s value, minus an implicit debt obligation. The implicit debt obligation is usually larger than the net value of the option itself.

A growth company therefore bears financial risk even if it does not borrow a dime explicitly. It makes sense for such a company to offset the financial risk created by growth options by reducing the amount of debt on its balance sheet. The implicit debt in its growth options ends up displacing explicit debt.

Growth options are less important for mature corporations. Such companies can and usually do borrow more. They often end up following the pecking order. Information problems deter large equity issues, so such firms prefer to finance investment with retained earnings.

They issue more debt when investments outrun retained earnings, and pay down debt when earnings outpace investment.

Sooner or later, a corporation’s operations age to the point where growth opportunities evaporate. In that case, the firm may issue large amounts of debt and retire equity, to constrain investment and force payout of cash to investors. The higher debt ratio may come voluntarily or be forced by a takeover.

These examples are not exhaustive, but they give some flavor of how a thoughtful CEO can set financing strategy.

Awsome article and straight to the point. I don’t know if this is actually the best place to ask but do you people have any thoughts on where to get some professional writers? Thanks in advance 🙂