A hacker is an individual who intends to gain unauthorized access to a computer system. Within the hacking community, the term cracker is typically used to denote a hacker with criminal intent, although in the public press, the terms hacker and cracker are used interchangeably. Hackers gain unauthorized access by finding weaknesses in the security protections websites and computer systems employ. Hacker activities have broadened beyond mere system intrusion to include theft of goods and information as well as system damage and cybervandalism, the intentional disruption, defacement, or even destruction of a website or corporate information system.

1. Spoofing and Sniffing

Hackers attempting to hide their true identities often spoof, or misrepresent, themselves by using fake email addresses or masquerading as someone else. Spoofing may also involve redirecting a web link to an address different from the intended one, with the site masquerading as the intended destination. For example, if hackers redirect customers to a fake website that looks almost exactly like the true site, they can then collect and process orders, effectively stealing business as well as sensitive customer information from the true site. We will provide more detail about other forms of spoofing in our discussion of computer crime.

A sniffer is a type of eavesdropping program that monitors information traveling over a network. When used legitimately, sniffers help identify potential network trouble spots or criminal activity on networks, but when used for criminal purposes, they can be damaging and very difficult to detect. Sniffers enable hackers to steal proprietary information from anywhere on a network, including email messages, company files, and confidential reports.

2. Denial-of-Service Attacks

In a denial-of-service (DoS) attack, hackers flood a network server or web server with many thousands of false communications or requests for services to crash the network. The network receives so many queries that it cannot keep up with them and is thus unavailable to service legitimate requests. A distributed denial-of-service (DDoS) attack uses numerous computers to inundate and overwhelm the network from numerous launch points.

Although DoS attacks do not destroy information or access restricted areas of a company’s information systems, they often cause a website to shut down, making it impossible for legitimate users to access the site. For busy e-commerce sites, these attacks are costly; while the site is shut down, customers cannot make purchases. Especially vulnerable are small and midsize businesses whose networks tend to be less protected than those of large corporations.

Perpetrators of DDoS attacks often use thousands of zombie PCs infected with malicious software without their owners’ knowledge and organized into a botnet. Hackers create these botnets by infecting other people’s computers with bot malware that opens a back door through which an attacker can give instructions. The infected computer then becomes a slave, or zombie, serving a master computer belonging to someone else. When hackers infect enough computers, they can use the amassed resources of the botnet to launch DDoS attacks, phishing campaigns, or unsolicited spam email.

Ninety percent of the world’s spam and 80 percent of the world’s malware are delivered by botnets. A recent example is the Mirai botnet, which infected numerous IoT devices (such as Internet-connected surveillance cameras) in October 2016 and then used them to launch a DDoS attack against Dyn, whose servers monitor and reroute Internet traffic. The Mirai botnet overwhelmed the Dyn servers, taking down Etsy, GitHub, Netflix, Shopify, SoundCloud, Spotify, Twitter, and a number of other major websites. A Mirai botnet variant attacked financial firms in January 2018.

3. Computer Crime

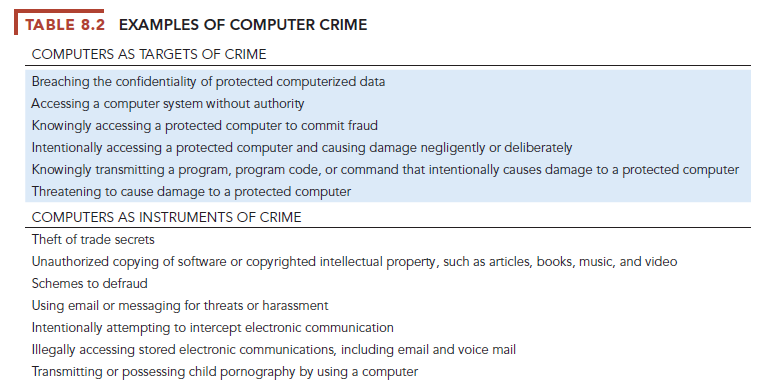

Most hacker activities are criminal offenses, and the vulnerabilities of systems we have just described make them targets for other types of computer crime as well. Computer crime is defined by the U.S. Department of Justice as “any violations of criminal law that involve a knowledge of computer technology for their perpetration, investigation, or prosecution.” Table 8.2 provides examples of the computer as both a target and an instrument of crime.

No one knows the magnitude of computer crime-how many systems are invaded, how many people engage in the practice, or the total economic damage. According to the Ponemon Institute’s 2017 Annual Cost of Cyber Crime Study, the average annualized cost of cybercrime security for benchmarked companies in seven different countries was $11.7 million (Ponemon Institute, 2017a). Many companies are reluctant to report computer crimes because the crimes may involve employees or that publicizing vulnerability will hurt their reputations. The most economically damaging kinds of computer crime are DoS attacks, activities of malicious insiders, and web-based attacks.

4. Identity Theft

With the growth of the Internet and electronic commerce, identity theft has become especially troubling. Identity theft is a crime in which an imposter obtains key pieces of personal information, such as social security numbers, driver’s license numbers, or credit card numbers, to impersonate someone else. The information may be used to obtain credit, merchandise, or services in the name of the victim or to provide the thief with false credentials. Identity theft has flourished on the Internet, with credit card files a major target of website hackers (see the chapter-ending case study). According to the 2018 Identity Fraud Study by Javelin Strategy & Research, identity fraud affected 16.7 million U.S. consumers in 2017, and they lost nearly $17 billion to identity fraud that year (Javelin, 2018).

One increasingly popular tactic is a form of spoofing called phishing. Phishing involves setting up fake websites or sending email messages that look like those of legitimate businesses to ask users for confidential personal data. The email message instructs recipients to update or confirm records by providing social security numbers, bank and credit card information, and other confidential data, either by responding to the email message, by entering the information at a bogus website, or by calling a telephone number. eBay, PayPal, Amazon.com, Walmart, and a variety of banks have been among the top spoofed companies. In a more targeted form of phishing called spear phishing, messages appear to come from a trusted source, such as an individual within the recipient’s own company or a friend.

Phishing techniques called evil twins and pharming are harder to detect. Evil twins are wireless networks that pretend to offer trustworthy Wi-Fi connections to the Internet, such as those in airport lounges, hotels, or coffee shops. The bogus network looks identical to a legitimate public network. Fraudsters try to capture passwords or credit card numbers of unwitting users who log on to the network.

Pharming redirects users to a bogus web page, even when the individual types the correct web page address into his or her browser. This is possible if pharming perpetrators gain access to the Internet address information Internet service providers (ISPs) store to speed up web browsing and flawed software on ISP servers allows the fraudsters to hack in and change those addresses.

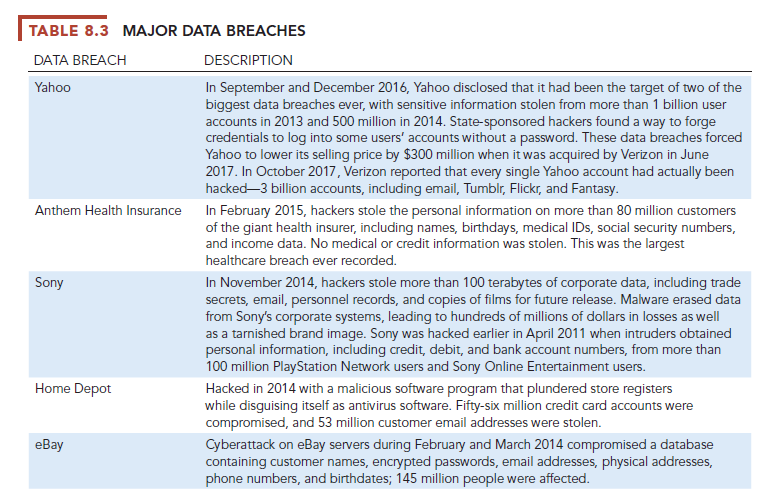

According to the Ponemon Institute’s 2017 Cost of a Data Breach Study, the average cost of a data breach among the 419 companies it surveyed globally was $3.62 million (Ponemon, 2017b). Moreover, brand damage can be significant although hard to quantify. In addition to the data breaches described in case studies for this chapter, Table 8.3 describes other major data breaches.

The U.S. Congress addressed the threat of computer crime in 1986 with the Computer Fraud and Abuse Act, which makes it illegal to access a computer system without authorization. Most states have similar laws, and nations in Europe have comparable legislation. Congress passed the National Information Infrastructure Protection Act in 1996 to make malware distribution and hacker attacks to disable websites federal crimes.

U.S. legislation, such as the Wiretap Act, Wire Fraud Act, Economic Espionage Act, Electronic Communications Privacy Act, CAN-SPAM Act, and Protect Act of 2003, covers computer crimes involving intercepting electronic communication, using electronic communication to defraud, stealing trade secrets, illegally accessing stored electronic communications, using email for threats or harassment, and transmitting or possessing child pornography. A proposed federal Data Security and Breach Notification Act would mandate organizations that possess personal information to put in place “reasonable” security procedures to keep the data secure and notify anyone affected by a data breach, but it has not been enacted.

5. Click Fraud

When you click an ad displayed by a search engine, the advertiser typically pays a fee for each click, which is supposed to direct potential buyers to its products. Click fraud occurs when an individual or computer program fraudulently clicks an online ad without any intention of learning more about the advertiser or making a purchase. Click fraud has become a serious problem at Google and other websites that feature pay-per-click online advertising.

Some companies hire third parties (typically from low-wage countries) to click a competitor’s ads fraudulently to weaken them by driving up their marketing costs. Click fraud can also be perpetrated with software programs doing the clicking, and botnets are often used for this purpose. Search engines such as Google attempt to monitor click fraud and have made some changes to curb it.

6. Global Threats: Cyberterrorism and Cyberwarfare

The cyber criminal activities we have described—launching malware, DoS attacks, and phishing probes—are borderless. Attack servers for malware are now hosted in more than 200 countries and territories. The leading sources of malware attacks include the United States, China, Brazil, India, Germany, and Russia. The global nature of the Internet makes it possible for cybercriminals to operate—and to do harm—anywhere in the world.

Internet vulnerabilities have also turned individuals and even entire nation-states into easy targets for politically motivated hacking to conduct sabotage and espionage. Cyberwarfare is a state-sponsored activity designed to cripple and defeat another state or nation by penetrating its computers or networks to cause damage and disruption. One example is the efforts of Russian hackers to disrupt the U.S. elections described in the chapter-opening case. The infamous 2014 hack on Sony has been attributed to state actors from North Korea. In 2017, the WannaCry and Petya cyber attacks, masquerading as ransomware, caused large-scale disruptions in Ukraine as well as to the UK’s National Health Service, pharmaceutical giant Merck, and other organizations around the world. Russians were suspected of conducting a cyberattack on Ukraine during a period of political turmoil in 2014. Cyberwarfare also includes defending against these types of attacks.

Cyberwarfare is more complex than conventional warfare. Although many potential targets are military, a country’s power grids, dams, financial systems, communications networks, and even voting systems can also be crippled. Non-state actors such as terrorists or criminal groups can mount attacks, and it is often difficult to tell who is responsible. Nations must constantly be on the alert for new malware and other technologies that could be used against them, and some of these technologies developed by skilled hacker groups are openly for sale to interested governments.

Cyberwarfare attacks have become much more widespread, sophisticated, and potentially devastating. Between 2011 and 2015, foreign hackers stole source code and blueprints to the oil and water pipelines and power grid of the United States and infiltrated the Department of Energy’s networks 150 times. Over the years, hackers have stolen plans for missile tracking systems, satellite navigation devices, surveillance drones, and leading-edge jet fighters.

According to U.S. intelligence, more than 30 countries are developing offensive cyberattack capabilities, including Russia, China, Iran, and North Korea. Their cyberarsenals include collections of malware for penetrating industrial, military, and critical civilian infrastructure controllers; email lists and text for phishing attacks on important targets; and algorithms for DoS attacks. U.S. cyberwarfare efforts are concentrated in the United States Cyber Command, which coordinates and directs the operations and defense of Department of Defense information networks and prepares for military cyberspace operations. Cyberwarfare poses a serious threat to the infrastructure of modern societies, since their major financial, health, government, and industrial institutions rely on the Internet for daily operations.

Source: Laudon Kenneth C., Laudon Jane Price (2020), Management Information Systems: Managing the Digital Firm, Pearson; 16th edition.

Good write-up, I am normal visitor of one’s site, maintain up the nice operate, and It is going to be a regular visitor for a long time.