Implementing e-procurement has the challenges of change management associated with any information system which are discussed in Chapter 10. If the implementation can mirror existing practices, then it will be most straightforward, but many of the benefits will not be gained and the use of new technology often forces new processes to be considered. CIPS (2008) forcefully make the case that some reengineering will be required when they state:

Organisations should not simply automate existing procurement processes and systems but should consider improving ways of working and re-engineering business processes prior to the implementation of eSourcing / eProcurement. Purchasing and supply management professionals should challenge established procurement practices to test whether these have evolved around a paper-based system and as such can be replaced. CIPS strongly recommends that, wherever possible, processes should be re-engineered prior to implementing ePurchasing.

Hildebrand (2002) illustrates the challenges of implementing e-procurement when he cites a 2002 Forrester Research poll of 50 global 3,500 companies. For these large, international companies, the biggest implementation ‘headache’ was rated as:

- Training/change management (32%)

- Supplier relationship management (30%)

- Catalogue management (10%)

- Project management (4%).

These problems are also indicated by Carrie Ericson, consultant at e-procurement supplier AT Kearney (www.ebreviate.com) in an interview (logistics.about, 2003). She says that in her experience:

Challenges often come down to our classic change management dilemmas: getting folks to change the way they conduct business, disrupting long standing supplier agreements, issues around politics and control.

In addition, the up front cost is often a challenge and the ROI [return on investment] can be perceived to be risky. I’m sure we’ve all heard a lot of stories about costly eprocure- ment implementations. Finally, the buyers are often nervous about perception. Will the new tools reflect that they have been doing a poor job in the past?

To introduce e-procurement the IS manager and procurement team must work together to find a solution that links together the different people and tasks of procurement shown in Figure 7.1. Historically, it has been easier to introduce systems that only cover some parts of the procurement cycle. Figure 7.4 shows how different types of information system cover different parts of the procurement cycle. The different type of systems are as follows.

- Stock control system – this relates mainly to production-related procurement; the system highlights when reordering is required when the number in stock falls below reorder thresholds.

- CD or web-based catalogue – paper catalogues have been replaced by electronic forms that make it quicker to find suppliers.

- E-mail- or database-based workflow systems integrate the entry of the order by the originator, approval by manager and placement by buyer. The order is routed from one person to the next and will wait in their in box for actioning. Such systems may be extended to accounting systems. Figure 7.5 shows an e-mail generated by an electronic procurement system as part of a workflow; it shows that a manager has approved the purchase requisition.

- Order-entry on web site – the buyer often has the opportunity to order directly on the supplier’s web site, but this will involve rekeying and there is no integration with systems for requisitioning or accounting.

- Accounting systems – networked accounting systems enable staff in the buying department to enter an order which can then be used by accounting staff to make payment when the invoice arrives.

- Integrated e-procurement or ERP systems – these aim to integrate all the facilities above and will also include integration with suppliers’ systems. Figure 7.6 shows document management software as an integrated part of an e-procurement system. Here a paper invoice from a supplier (on the left) has been scanned into the system and is compared to the original electronic order information (on the right).

Companies face a difficult choice in achieving full-cycle e-procurement since they have the option of trying to link different systems or purchasing a single new system that integrates the facilities of the previous systems. Purchasing a new system may be the simplest technical option, but it may be more expensive than trying to integrate existing systems and it also requires retraining in the system.

1. The growth in adoption of web-enabled e-procurement

Conspectus (2006) research showed that many UK organizations have now invested in web- enabled e-procurement. However, a mix of systems is used, with 92% using the web for some aspects of procurement, but with 85% still using fax and 65% traditional EDI. The transition from EDI to web EDI is continuing with 82% stating they plan to increase their use of the web between 2006 and 2007. In the survey the main benefits of the e-procurement approach are reduced costs (77%), along with improved service (63%), greater responsiveness (63%), improved supplier relationships (63%) and better collaboration with suppliers (55%).

Within SMEs, as would be expected, use of e-procurement is low. FT.com (2006) reported that within SMEs, the use of online procurement is low. A postal survey of 167 SMEs by the Chartered Institute of Purchasing and Supply found that only 37% had used the web to tender for business despite 73% having an Internet connection. The main reason given by those who had not tendered for contracts online was a belief that ‘the industry does not use online tendering (31%), lack of skills (17%), complexity (14%), lack of opportunity (12%) and mistrust of the process (11%). The benefits cited by SMEs currently selling goods and services online include speed of process (52%), cost savings (26%), reduced paperwork (26%), increased customer satisfaction (18%) and increased productivity (16%).

The results from these surveys suggest that e-procurement is undertaken for some activities, but not all. This is backed up by an earlier survey conducted by AT Kearney, quoted in logistics.about (2003). This showed that although 96% of US companies surveyed were engaged in some form of e-procurement, typically these activities only covered a limited portion, on average 11% of the spend base. While it tends to be higher for indirect materials (up to 15%), it is lower for services (4% on average). However, where e-procurement is used it delivers savings of as much as 40%. These savings come from purchased cost reduction as well as decreased order cycle time and headcount reduction.

2. Integrating company systems with supplier systems

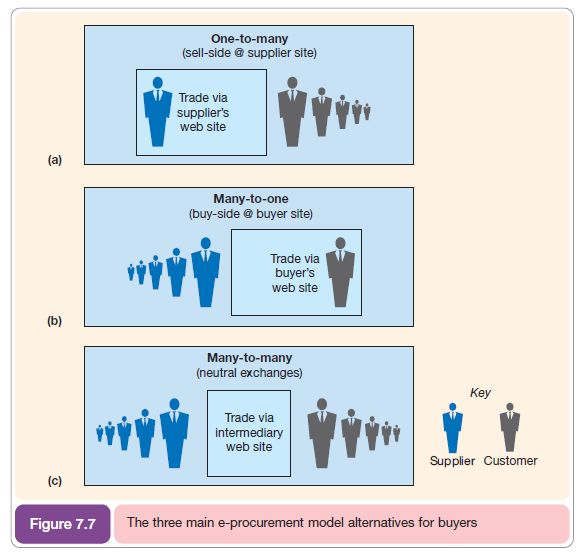

We saw from the Shell case study in Chapter 6, the cost and cycle-time benefits that a company can achieve through linking its systems with those of its suppliers. If integrating systems within a company is difficult, then linking with other companies’ systems is more so. This situation arises since suppliers will use different types of systems and different models for integration. As explained in Chapter 2, there are three fundamental models for location of B2B e-commerce: sell-side, buy-side and marketplace-based. These alternative options for procurement links with suppliers are summarized in Figure 7.7 and the advantages and disadvantages of each are summarized in Table 7.8.

Chapter 2 explained that companies supplying products and services had to decide which combination of these models would be used to distribute their products. From the buyer’s point of view, they will be limited by the selling model their suppliers have adopted.

Figure 7.8 shows options for integration for a buyer who is aiming to integrate an internal system such as an ERP system with external systems. Specialized e-procurement software may be necessary to interface with the ERP system. This could be a special e-procurement application or it could be middleware to interface with an e-procurement component of an ERP system. How does the e-procurement system access price catalogues from suppliers? There are two choices shown on the diagram. Choice (a) is to house electronic catalogues from different suppliers inside the company and firewall. This traditional approach has the benefit that the data are housed inside the company and so can be readily accessed. However, electronic links beyond the firewall will be needed to update the catalogues, or this is sometimes achieved via delivery of a CD with the updated catalogue. Purchasers will have a single integrated view of products from different suppliers as shown in Figure 7.9. Choice (b) is to punch out through the firewall to access catalogues either on a supplier site or at an intermediary site. One of the benefits of linking to an intermediary site such as a B2B exchange is that this has done the work of collecting data from different suppliers and producing it in a consistent format. However, this is also done by suppliers of aggregated data.

Source: Dave Chaffey (2010), E-Business and E-Commerce Management: Strategy, Implementation and Practice, Prentice Hall (4th Edition).

Woah! I’m really enjoying the template/theme of this blog. It’s simple, yet effective. A lot of times it’s hard to get that “perfect balance” between usability and visual appeal. I must say you’ve done a amazing job with this. In addition, the blog loads extremely fast for me on Opera. Exceptional Blog!