1. Bond Terms

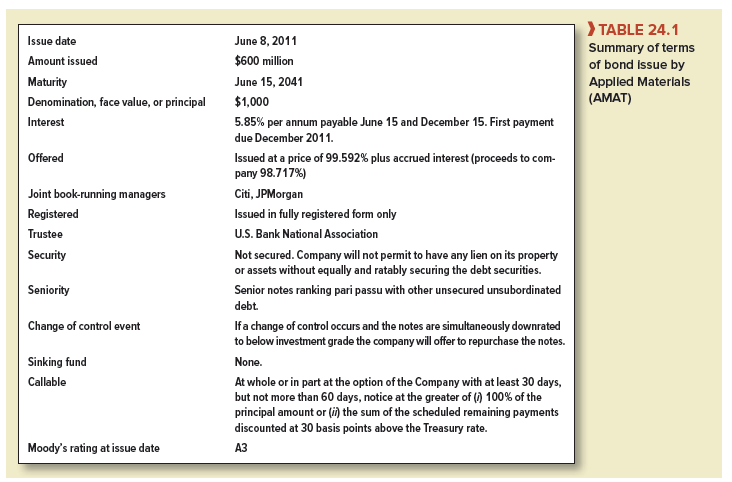

Applied Materials (AMAT) supplies equipment and software for the manufacture of semiconductors. In 2011, AMAT issued 30-year bonds to help finance an acquisition. The bond was a plain-vanilla issue; in other words, it was pretty well standard in every way. To give you some feel for the bond contract (and for some of the language in which it is couched), we have summarized in Table 24.1 the terms of the issue. We will look in turn at its principal features.

The AMAT bond was issued in 2011 and is due to mature 30 years later in 2041. It was issued in denominations of $1,000. So, at maturity, the company will repay the principal amount of $1,000 to the holder of each bond.

The annual interest or coupon payment on the bond is 5.85% of $1,000, or $58.50. This interest is payable semiannually, so every six months the bondholder receives interest of 58.50/2 = $29.25. Most U.S. bonds pay interest semiannually, but in many other countries it is common to pay interest annually.

The regular interest payment on a bond is a hurdle that the company must keep jumping. If AMAT ever fails to make the payment, lenders can demand their money back instead of waiting until matters deteriorate further.[2] Thus, regular interest payments provide added protection for lenders.

Sometimes bonds are sold with a lower coupon payment but at a significant discount on their face value, so investors receive much of their return in the form of capital appreciation.[3] The ultimate is the zero-coupon bond, which pays no interest at all; in this case, the entire return consists of capital appreciation.[4]

The AMAT interest payment is fixed for the life of the bond, but in some issues the payment varies with the general level of interest rates. For example, the payment may be set at 1% over the U.S. Treasury bill rate or (more commonly) over the London interbank offered rate (LIBOR), which is the rate at which international banks borrow from one another. Sometimes these floating-rate notes specify a minimum (or floor) interest rate, or they may specify a maximum (or cap) on the rate.[5] You may also come across “collars,” which stipulate both a maximum and a minimum payment.

The AMAT bonds have a face value of $1,000 and were sold to investors at 99.592% of face value. In addition, buyers had to pay any accrued interest. This is the amount of any future interest that has accumulated by the time of the purchase. For example, investors who bought bonds for delivery on (say) October 15, would have only two months to wait before receiving their first interest payment. Therefore, the four months of accrued interest would be (120/360) x 5.85 = 1.95%, and the investor would need to pay the purchase price of the bond plus 1.95%.7

Although the AMAT bonds were offered to the public at a price of 99.592%, the company received only 98.717%. The difference represents the underwriters’ spread. Of the $597.6 million raised, $592.3 million went to the company and $5.3 million (or about .9%) went to the underwriters.

Moving down Table 24.1, you see that the AMAT’s bonds are registered. This means that the company’s registrar records the ownership of each bond and the company pays the interest and final principal amount directly to each owner. Almost all bonds in the United States are issued in registered form, but in many countries, companies may issue bearer bonds. In this case, the bond certificate constitutes the primary evidence of ownership, so the bondholder must return the certificate to the company to claim the final repayment of principal.

The AMAT bonds were sold publicly to investors. Before it could sell the bonds, it needed to file a registration statement for approval of the SEC and to prepare a prospectus. The bond was issued under an indenture, or trust deed, between the company and a trustee. U.S. Bank National Association, which is the trust company for the issue, represents the bondholders. It must see that the terms of the indenture are observed and look after the bondholders in the event of default. The bond indenture is a turgid legal document that is bedtime reading only for insomniacs.8 However, the main provisions are described in the prospectus to the issue.

2. Security and Seniority

Sometimes a company sets aside particular assets for the protection of the bondholder. For example, utility company bonds are often secured. In this case, if the company defaults on its debt, the trustee or lender may take possession of the relevant assets. If these are insufficient to satisfy the claim, the remaining debt will have a general claim, alongside any unsecured debt, on the other assets of the firm.

Unsecured bonds maturing in 10 years or fewer are usually called notes, while longer-term issues may be called bonds (as in the case of the AMAT bond) or debentures.9 Like most bond issues by industrial and financial companies, the AMAT bonds are unsecured. In that case, it is common for the issue to include a so-called negative pledge clause that promises that the company will not issue any secured bonds without offering the same security to its unsecured bonds.

The majority of secured bonds are mortgage bonds. These sometimes provide a claim against a specific building, but they are more often secured on all of the firm’s property.

Of course, the value of any mortgage depends on the extent to which the property has alternative uses. A custom-built machine for producing buggy whips will not be worth much when the market for buggy whips dries up.

Companies that own securities may use them as collateral for a loan. For example, holding companies are firms whose main assets consist of common stock in a number of subsidiaries. So, when holding companies wish to borrow, they generally use these investments as collateral. In such cases, the problem for the lender is that the stock is junior to all other claims on the assets of the subsidiaries, and so these collateral trust bonds usually include detailed restrictions on the freedom of the subsidiaries to issue debt or preferred stock.

A third form of secured debt is the equipment trust certificate. This is most frequently used to finance new railroad rolling stock but may also be used to finance trucks, aircraft, and ships. Under this arrangement, a trustee obtains formal ownership of the equipment. The company makes a down payment on the cost of the equipment, and the balance is provided by a package of equipment trust certificates with different maturities that might typically run from 1 to 15 years. Only when all these debts have finally been paid off does the company become the formal owner of the equipment. Bond rating agencies such as Moody’s or Standard & Poor’s usually rate equipment trust certificates one grade higher than the company’s regular debt.

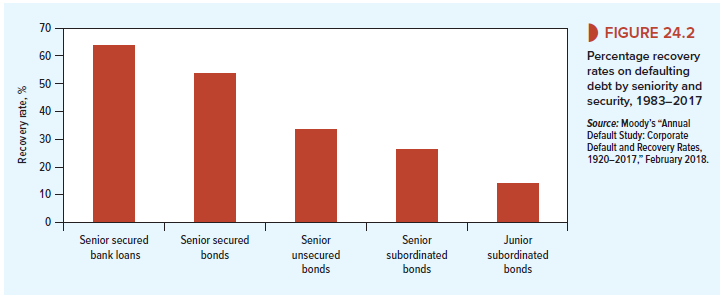

Bonds may be senior claims or they may be subordinated to the senior bonds or to all other creditors.11 If the firm defaults, the senior bonds come first in the pecking order. The subordinated lender gets in line behind the general creditors but ahead of the preferred stockholders and the common stockholders.

As you can see from Figure 24.2, if default does occur, it pays to hold senior secured bonds. On average, investors in these bonds can expect to recover over 50% of the amount of the loan. At the other extreme, recovery rates for junior unsecured bondholders are only 14% of the face value of the debt.

3. Asset-Backed Securities

Instead of borrowing money directly, companies sometimes bundle up a group of assets and then sell the cash flows from these assets. This issue is known as an asset-backed security, or ABS. The debt is secured, or backed, by the underlying assets.

Suppose your company has made a large number of mortgage loans to buyers of homes or commercial real estate. However, you don’t want to wait until the loans are paid off; you would like to get your hands on the money now. Here is what you do. You establish a separate, special-purpose company that buys a package of the mortgage loans. To finance this purchase, the company sells mortgage-backed securities. The holders of these bonds simply receive a share of the mortgage payments. For example, if interest rates fall and the mortgages are repaid early, holders of the bonds are also repaid early. That is not generally popular with these holders because they get their money back just when they don’t want it—when interest rates are low.

Instead of issuing one class of bonds, a pool of mortgages can be bundled and then split into different slices (or tranches), known as collateralized debt obligations, or CDOs. For example, mortgage payments might be used first to pay off one class of security holders and only then will other classes start to be repaid. The senior tranches have first claim on the cash flows and therefore may be attractive to conservative investors such as insurance companies or pension funds. The riskiest (or equity) tranche can then be sold to hedge funds or mutual funds that specialize in low-quality debt.

Real estate lenders are not unique in wanting to turn future cash receipts into up-front cash. Automobile loans, student loans, and credit card receivables are also often bundled and remarketed as an asset-backed security. Indeed, investment bankers seem able to repackage any set of cash flows into a loan. In 1997, David Bowie, the British rock star, established a company that then purchased the royalties from his current albums. The company financed the purchase by selling $55 million of 10-year notes. The royalty receipts were used to make the principal and interest payments on the notes. When asked about the singer’s reaction to the idea, his manager replied, “He kind of looked at me cross-eyed and said ‘What?’”[10]

The process of bundling a number of future cash flows into a single security is called securitization. You can see the arguments for securitization. As long as the risks of the individual loans are not perfectly correlated, the risk of the package is less than that of any of the parts. In addition, securitization distributes the risk of the loans widely and, because the package can be traded, investors are not obliged to hold it to maturity.

In the years leading up to the financial crisis, the proportion of new mortgages that were securitized expanded sharply, while the quality of the mortgages declined. By 2007, more than half of the new issues of CDOs involved exposure to subprime mortgages. Because the mortgages were packaged together, investors in these CDOs were protected against the risk of default on an individual mortgage. However, even the senior tranches were exposed to the risk of an economywide slump in the housing market. For this reason, the debt has been termed “economic catastrophe debt.”

Economic catastrophe struck in the summer of 2007, when the investment bank Bear Stearns revealed that two of its hedge funds had invested heavily in nearly worthless CDOs. Bear Stearns was rescued with help from the Federal Reserve, but it signaled the start of the credit crunch and the collapse of the CDO market. By 2009, issues of CDOs had effectively disappeared.

Did this collapse reflect a fundamental flaw in the practice of securitization? A bank that packages and resells its mortgage loans spreads the risk of those loans. However, the danger is that when a bank can earn juicy fees from securitization, it might not worry so much if the loans in the package are junk.

4. Call Provisions

Back to our AMAT bond. The bond includes a call option that allows the company to repay the debt early. This can be a valuable option if AMAT wishes to reduce its leverage or tidy up its outstanding debt. The price at which companies could call their bonds used to be set at a fixed number. In this case, issuers had an incentive to call the bonds whenever they were worth more than the call price. This was not popular with investors. These days, it is more common to link the call price to an estimate of the bond’s value. Thus, if interest rates fall and the bond increases in value, AMAT must pay more than face value to buy back its bonds. The formula for determining this price seeks to ensure that AMAT can never buy back the bond for less than it is worth.

Very occasionally you come across bonds that give investors the repayment option. Extendible bonds give them the option to extend the bond’s life, while retractable (or puttable) bonds give investors the right to demand early repayment. Puttable bonds exist largely because bond indentures cannot anticipate every action the company may take that could harm the bondholder. If the value of the bonds is reduced, the put option allows the bondholders to demand repayment.

Puttable loans can sometimes get their issuers into BIG trouble. During the 1990s, many loans to Asian companies gave their lenders a repayment option. Consequently, when the Asian crisis struck in 1997, these companies were faced by a flood of lenders demanding their money back.

5. Sinking Funds

The AMAT bond must be repaid in its entirety in 2041. But in many cases, a bond issue is repaid on a regular basis before maturity. To do this, the company makes a series of payments into a sinking fund. If the payment is in the form of cash, the trustee selects bonds by lottery and uses the cash to redeem them at their face value.[14] Alternatively, the company can choose to buy bonds in the marketplace and pay these into the fund. This is a valuable option for the company. If the bond price is low, the firm will buy the bonds in the market and hand them to the sinking fund; if the price is high, it will call the bonds by lottery.

Generally, there is a mandatory fund that must be satisfied and an optional fund that can be satisfied if the borrower chooses. We saw earlier that interest payments provide a regular test of solvency. A sinking fund provides an additional hurdle that the firm must keep jumping. If it cannot pay the cash into the sinking fund, the lenders can demand their money back. That is why long-dated, lower-quality issues involve larger sinking funds. Higher-quality bonds generally have a lighter sinking fund requirement if they have one at all.

Unfortunately, a sinking fund is a weak test of solvency if the firm is allowed to repurchase bonds in the market. Since the market value of the debt declines as the firm approaches financial distress, the sinking fund becomes a hurdle that gets progressively lower as the hurdler gets weaker.

6. Bond Covenants

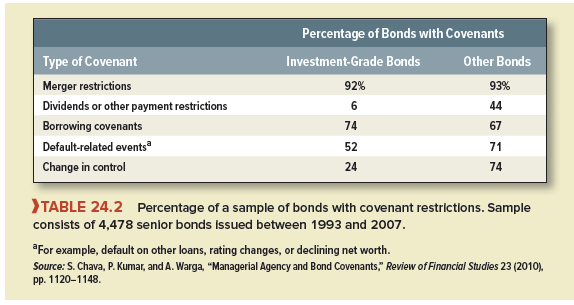

Investors in corporate bonds know that there is a risk of default. But they still want to make sure that the company plays fair. They don’t want it to gamble with their money. Therefore, the loan agreement usually includes a number of debt covenants that prevent the company from purposely increasing the value of its default option.[15] These covenants may be relatively light for blue-chip companies but more restrictive for smaller, riskier borrowers.

Lenders worry that after they have made the loan, the company may pile up more debt and so increase the chance of default. They protect themselves against this risk by prohibiting the company from making further debt issues unless the ratio of debt to equity is below a specified limit.

Not all debts are created equal. If the firm defaults, the senior debt comes first in the pecking order and must be paid off in full before the junior debtholders get a cent. Therefore, when a company issues senior debt, the lenders will place limits on further issues of senior debt. But they won’t restrict the amount of junior debt that the company can issue. Because the senior lenders are at the front of the queue, they view the junior debt in the same way that they view equity: They would be happy to see an issue of either. Of course, the converse is not true. Holders of the junior debt do care both about the total amount of debt and the proportion that is senior to their claim. As a result, an issue of junior debt generally includes a restriction on both total debt and senior debt.

All bondholders worry that the company may issue more secured debt. An issue of mortgage bonds often imposes a limit on the amount of secured debt. This is not necessary when you are issuing unsecured debentures. As long as the debenture holders are given an equal claim, they don’t care how much you mortgage your assets. Therefore, unsecured bonds usually include a so-called negative-pledge clause, in which the unsecured holders simply say, “Me too.”[16] We saw earlier that the AMAT bonds include a negative pledge clause.

Instead of borrowing money to buy an asset, companies may enter into a long-term agreement to rent or lease it. For the debtholder, this is very similar to secured borrowing. Therefore, debt agreements also include limitations on leasing.

We have talked about how an unscrupulous borrower can try to increase the value of the default option by issuing more debt. But this is not the only way that such a company can exploit its existing bondholders. For example, the value of the default option is increased when the company pays out some of its assets to stockholders. In the extreme case a company could sell all its assets and distribute the proceeds to shareholders as a bumper dividend. That would leave nothing for the lenders. To guard against such dangers, debt issues may restrict the amount that the company may pay out in the form of dividends or repurchases of stock.[17]

Take a look at Table 24.2, which summarizes the principal covenants in a large sample of senior bond issues. These covenants prevent the company from taking certain actions that would reduce the value of their bonds. Notice that investment-grade bonds tend to have fewer restrictions than high-yield bonds. For example, restrictions on the amount of any dividends or repurchases are less common in the case of investment-grade bonds.

These debt covenants do matter. Asquith and Wizman, who studied the effect of leveraged buyouts on the value of the company’s debt, found that when there were no restrictions on further debt issues, dividend payments, or mergers, the buyout led to a 5.2% fall in the value of existing bonds. Those bonds that were protected by strong covenants against excessive borrowing increased in price by 2.6%.

Unfortunately, it is not easy to cover all loopholes, as the bondholders of Marriott Corporation discovered in 1992. They hit the roof when the company announced plans to divide its operations into two separate businesses. One business, Marriott International, would manage Marriott’s hotel chain and receive most of the revenues, while the other, Host Marriott, would own all the company’s real estate and be responsible for servicing essentially all of the old company’s $3 billion of debt. As a result, the price of Marriott’s bonds plunged nearly 30%, and investors began to think about how they could protect themselves against such event risks. It is now more common for bondholders to insist on clauses that oblige the borrower to repay the debt if there is a change of control and the bonds are downrated. You can see that the AMAT bond included such a clause.

7. Privately Placed Bonds

The AMAT notes were registered with the SEC and sold publicly. However, bonds may also be placed privately with a few financial institutions, though the market for privately placed bonds is much smaller than the public market.

As we saw in Section 15-5, it costs less to arrange a private placement than to make a public debt issue. But there are other differences between a privately placed bond and its public counterpart.

First, if you place an issue privately with one or two financial institutions, it may be necessary to sign only a simple promissory note. This is just an IOU that lays down certain conditions that the borrower must observe. However, when you make a public issue of debt, you must worry about who is supposed to represent the bondholders in any subsequent negotiations and what procedures are needed for paying interest and principal. Therefore, the contract has to be more complicated.

The second characteristic of publicly issued bonds is that they are somewhat standardized products. They have to be—investors are constantly buying and selling without checking the fine print in the agreement. This is not so necessary in private placements, so the debt can be custom-tailored for firms with special problems or opportunities. The relationship between borrower and lender is much more intimate. Imagine a $200 million debt issue placed privately with an insurance company, and compare it with an equivalent public issue held by 200 anonymous investors. The insurance company can justify a more thorough investigation of the company’s prospects and, therefore, may be more willing to accept unusual terms or conditions.

These features of private placements give them a particular niche in the corporate debt market—namely, relatively low-grade loans to small- and medium-sized firms.[21] These are the firms that face the highest costs in public issues, that require the most detailed investigation, and that may require specialized, flexible loan arrangements.

Of course, the advantages of private placements are not free, for the lenders demand a higher rate of interest to compensate them for holding an illiquid asset. It is difficult to generalize about the difference in interest rates between private placements and public issues, but a typical differential is 50 basis points, or .50 percentage point.

8. Foreign Bonds and Eurobonds

AMAT’s bonds were registered with the SEC, denominated in dollars, and were marketed to investors in the United States and overseas. If the company had needed the cash for a project in another country, it might have preferred to issue debt in that country’s currency. For example, it could have sold sterling bonds in the U.K. or Swiss franc bonds in Switzerland. Foreign currency bonds that are sold to local investors in another country are known as foreign bonds. Many foreign companies issue their bonds in the United States, making it by far the largest market for foreign bonds. Japan and Switzerland are also substantial markets. Foreign bonds have a variety of nicknames. For example, a bond sold by a foreign company in the United States is known as a yankee bond, a bond sold by a foreign firm in Japan is a samurai, and one sold in Switzerland is an alpine.

Of course, any firm that raises money from local investors in a foreign country is subject to the rules of that country and oversight by its financial regulator. For example, when a foreign company issues publicly traded bonds in the United States, it must first register the issue with the SEC. However, as long as the bonds are not publicly traded, foreign firms borrowing in the United States can avoid registration by complying with the SEC’s Rule 144A. Rule 144A bonds can be bought and sold only by large financial institutions.

Instead of issuing a bond in a particular country’s market, a company may market a bond issue internationally. Issues that are denominated in one country’s currency but marketed internationally outside that country are known as eurobonds and are usually made in one of the major currencies, such as the U.S. dollar, the euro, or the yen. For example, AMAT could have issued a dollar bond just to overseas investors. As long as the issue is not marketed to U.S. investors, it does not need to be registered with the SEC. Eurobond issues are marketed by international syndicates of underwriters, such as the London branches of large U.S., European, and Japanese banks and security dealers. Be careful not to confuse a eurobond (which is outside the oversight of any domestic regulator and may be in any currency) with a bond that is marketed in a European country and denominated in euros.

The eurobond market arose during the 1960s because the U.S. government imposed a tax on the purchase of foreign securities and discouraged American corporations from exporting capital. Consequently, both European and American multinationals were forced to tap an international market for capital. The tax was removed in 1974. Since firms can now choose whether to borrow in New York or London, the interest rates in the two markets are usually similar. However, the eurobond market is not directly subject to regulation by the U.S. authorities, and therefore, the financial manager needs to be alert to small differences in the cost of borrowing in one market rather than another.

I have been checking out some of your posts and it’s pretty clever stuff. I will surely bookmark your website.