Hedging involves taking on one risk to offset another. It potentially removes all uncertainty, eliminating the chance of both happy and unhappy surprises. We explain shortly how to set up a hedge, but first we give some examples and describe some tools that are specially designed for hedging. These are forwards, futures, and swaps. Together with options, they are known as derivative instruments or derivatives because their value depends on the value of another asset.

1. A Simple Forward Contract

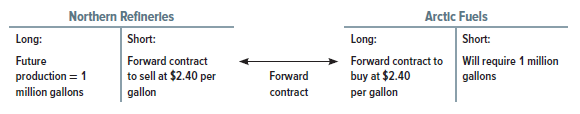

We start with an example of a simple forward contract. Arctic Fuels, the heating-oil distributor, plans to deliver one million gallons of heating oil to its retail customers next January. Arctic worries about high heating-oil prices next winter and wants to lock in the cost of buying its supply. Northern Refineries is in the opposite position. It will produce heating oil next winter, but doesn’t know what the oil can be sold for. So the two firms strike a deal: Arctic Fuels agrees in September to buy one million gallons from Northern Refineries at $2.40 per gallon, to be paid on delivery in January. Northern agrees to sell and deliver one million gallons to Arctic in January at $2.40 per gallon.

Arctic and Northern are now the two counterparties in a forward contract. The forward price is $2.40 per gallon. This price is fixed today, in September in our example, but payment and delivery occur later. (The price for immediate delivery is called the spot price.) Arctic, which has agreed to buy in January, has the long position in the contract. Northern Refineries, which has agreed to sell in January, has the short position.

We can think of each counterparty’s long and short positions in balance-sheet format, with long positions on the left (asset) side and short positions on the right (liability) side.

Northern Refineries starts with a long position because it will produce heating oil. Arctic Fuels starts with a short position, because it will have to buy to supply its customers. The forward contract creates an offsetting short position for Northern Refineries and an offsetting long position for Arctic Fuels. The offsets mean that each counterparty ends up locking in a price of $2.40, regardless of what happens to future spot prices.

Do not confuse this forward contract with an option. Arctic does not have the option to buy. It has committed to buy at $2.40 per gallon, even if spot prices in January turn out much lower than this. Northern does not have the option to sell. It cannot back away from the deal, even if spot prices for delivery in January turn out much higher than $2.40 per gallon. Note, however, that both the distributor and refiner have to worry about counterparty risk, that is, the risk that the other party will not perform as promised.

We confess that our heating oil example glossed over several complications. For example, we assumed that the risk of both companies is reduced by locking in the price of heating oil. But suppose that the retail price of heating oil moves up and down with the wholesale price. In that case the heating-oil distributor is naturally hedged because costs and revenues move together. Locking in costs with a futures contract could actually make the distributor’s profits more volatile.

2. Futures Exchanges

Our heating-oil distributor and refiner do not have to negotiate a one-off, bilateral contract. Each can go to an exchange where standardized forward contracts on heating oil are traded. The distributor would buy contracts and the refiner would sell.

Here we encounter some tricky vocabulary. When a standardized forward contract is traded on an exchange, it is called a futures contract—same contract, but a different label. The exchange is called a futures exchange. The distinction between “futures” and “forward” does not apply to the contract, but to how the contract is traded. We describe futures trading in a moment.

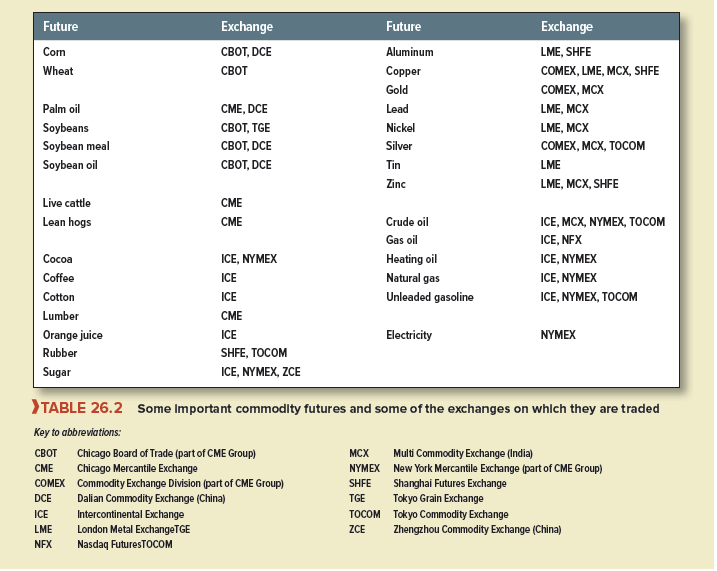

Table 26.2 lists a few of the most important commodity futures contracts and the exchanges on which they are traded.[1] Our refiner and distributor can trade heating-oil futures on the New York Mercantile Exchange (NYMEX). A forest products company and a homebuilder can trade lumber futures on the Chicago Mercantile Exchange (CME). A wheat farmer and a miller can trade wheat futures on the Chicago Board of Trade (CBOT) or on a smaller regional exchange.

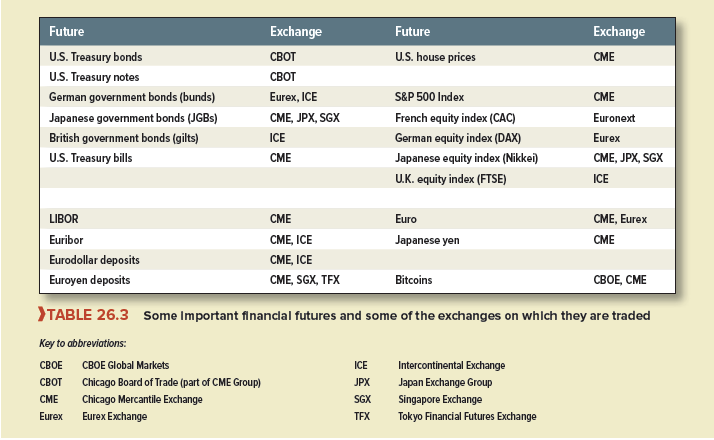

For many firms, the wide fluctuations in interest rates and exchange rates have become at least as important a source of risk as changes in commodity prices. Financial futures are similar to commodity futures, but instead of placing an order to buy or sell a commodity at a future date, you place an order to buy or sell a financial asset at a future date. Table 26.3 lists some important financial futures. Like Table 26.2 it is far from complete. For example, you can also trade futures on the Thai stock market index, the Chilean peso, Spanish government bonds, and many other financial assets.

Almost every day, some new futures contract seems to be invented. At first, there may be just a few private deals between a bank and its customers, but if the idea proves popular, one of the futures exchanges will try to muscle in on the business. For example, in 2017 the Chicago Mercantile Exchange and the CBOE Futures Exchange began to offer futures contracts on the bitcoin.

3. The Mechanics of Futures Trading

When you buy or sell a futures contract, the price is fixed today but payment is not made until later. You will, however, be asked to put up margin in the form of either cash or Treasury bills to demonstrate that you have the money to honor your side of the bargain. As long as you earn interest on the margined securities, there is no cost to you.

In addition, futures contracts are marked to market. This means that each day any profits or losses on the contract are calculated; you pay the exchange any losses and receive any profits. For example, suppose that in September Arctic Fuels buys 1 million gallons of January heating-oil futures contracts at a futures price of $2.40 per gallon. The next day the price of the January contract increases to $2.44 per gallon. Arctic now has a profit of $.04 x 1,000,000 = $40,000. The exchange’s clearinghouse therefore pays $40,000 into Arctic’s margin account. If the price then drops back to $2.42, Arctic’s margin account pays $20,000 back to the clearing house.

Of course, Northern Refineries is in the opposite position. Suppose it sells 1 million gallons of January heating-oil futures contracts at a futures price of $2.40 per gallon. If the price increases to $2.44 cents per gallon, it loses $.04 x 1,000,000 = $40,000 and must pay this amount into the clearinghouse. Notice that neither the distributor nor the refiner has to worry about whether the other party will honor the other side of the bargain. The futures exchange guarantees the contracts and protects itself by settling up profits or losses each day. Futures trading eliminates counterparty risk.

Now consider what happens over the life of the futures contract. We’re assuming that Arctic and Northern take offsetting long and short positions in the January contract (not directly with each other, but with the exchange). Suppose that a severe cold snap pushes the spot price of heating oil in January up to $2.60 per gallon. Then the futures price at the end of the contract will also be $2.60 per gallon.[2] So Arctic gets a cumulative profit of (2.60 – 2.40) x 1,000,000 = $200,000. It can take delivery of 1 million gallons, paying $2.60 per gallon, or $2,600,000. Its net cost, counting the profits on the futures contract, is $2,600,000 – 200,000 = $2,400,000, or $2.40 per gallon. Thus it has locked in the $2.40 per gallon price quoted in September when it first bought the futures contract. You can easily check that Arctic’s net cost always ends up at $2.40 per gallon, regardless of the spot price and ending futures price in January.

Northern Refineries suffers a cumulative loss on the futures contract of $200,000 if the January price is $2.60. That’s the bad news; the good news is that it can sell and deliver heating oil for $2.60 per gallon. Its net revenues are $2,600,000 – 200,000 = $2,400,000, or $2.40 per gallon, the futures price in September. Again, you can easily check that Northern’s net selling price always ends up at $2.40 per gallon.

Taking delivery directly from an exchange can be costly and inconvenient. For example, the NYMEX heating-oil contract calls for delivery in New York Harbor. Arctic Fuels will be better off taking delivery from a local source such as Northern Refineries. Northern Refineries will likewise be better off delivering heating oil locally than shipping it to New York. Therefore, both parties will probably close out their futures positions just before the end of the contract, and take their profits or losses.[3] Nevertheless the NYMEX futures contract has allowed them to hedge their risks.

The effectiveness of this hedge depends on the correlation between changes in heating-oil prices locally and in New York Harbor. Prices in both locations will be positively correlated because of a common dependence on world energy prices. But the correlation is not perfect. What if a local cold snap hits Arctic Fuels’s customers but not New York? A long position in NYMEX futures won’t hedge Arctic Fuels against the resulting increase in the local spot price. This is an example of basis risk. We return to the problems created by basis risk later in this chapter.

4. Trading and Pricing Financial Futures Contracts

Financial futures trade in the same way as commodity futures. Suppose your firm’s pension fund manager thinks that the French stock market will outperform other European markets over the next six months. She forecasts a 10% six-month return. How can she place a bet? She can buy French stocks, of course. But she could also buy futures contracts on the CAC index

of French stocks, which are traded on the Euronext exchange. Suppose she buys 15 six-month futures contracts at 5,000. Each contract pays off 10 times the level of the index, so she has a long position of 15 X 10 X 5,000 = €750,000. This position is marked to market daily. If the CAC goes up, the exchange puts the profits into your fund’s margin account; if the CAC falls, the margin account falls too. If your pension manager is right about the French market, and the CAC ends up at 5,500 after six months, then your fund’s cumulative profit on the futures position is 15 X (5,500 – 5,000) X 10 = €75,000.

If you want to buy a security, you have a choice. You can buy for immediate delivery at the spot price, or you can “buy forward” by placing an order for future delivery at the futures price. You end up with the same security either way, but there are two differences. First, if you buy forward, you don’t pay up front, and so you can earn interest on the purchase price.[4] Second, you miss out on any interest or dividend that is paid in the meantime. This tells us the relationship between spot and futures prices:

![]()

where Ft is the futures price for a contract lasting t periods, S0 is today’s spot price, rf is the risk-free interest rate, and y is the dividend yield or interest rate.[5] The following example shows how and why this formula works.

EXAMPLE 26.1 ● Valuing Index Futures

Suppose that the six-month CAC futures contract trades at 5,000 when the current (spot) CAC index is 5,045.41. The interest rate is 1% per year (about .5% over six months) and the dividend yield on the index is 2.8 (about 1.4% over six months). These numbers fit the formula perfectly because

Ft = 5,045.41 X (1 + .005 – .014) = 5,000

But why are the numbers consistent?

Suppose you just buy the CAC index for 5,045.41 today. Then in six months, you will own the index and also have dividends of .014 X 5,045.41 = 70.64. But you decide to buy a futures contract for 5,000 instead, and you put €5,045.41 in the bank. After six months, the bank account has earned interest at .5%, so you have 5,045.41 X 1.005 = 5,070.64, enough to buy the index for 5,000 with €70.64 left over—just enough to cover the dividend you missed by buying futures rather than spot. You get what you pay for.[6]

5. Spot and Futures Prices—Commodities

The difference between buying commodities today and buying commodity futures is more complicated. First, because payment is again delayed, the buyer of the future earns interest on her money. Second, she does not need to store the commodities and, therefore, saves warehouse costs, wastage, and so on. On the other hand, the futures contract gives no convenience yield, which is the value of being able to get your hands on the real thing. The manager of a supermarket can’t burn heating-oil futures if there’s a sudden cold snap, and he can’t stock the shelves with orange juice futures if he runs out of inventory at 1 p.m. on a Saturday.

Let’s express storage costs and convenience yield as fractions of the spot price. For commodities, the futures price for t periods ahead is[7]

![]()

It’s interesting to compare this formula with the formula for a financial future. Convenience yield plays the same role as dividends or interest foregone (y) on securities. But financial assets cost nothing to store, and storage costs do not appear in the formula for financial futures.

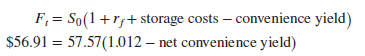

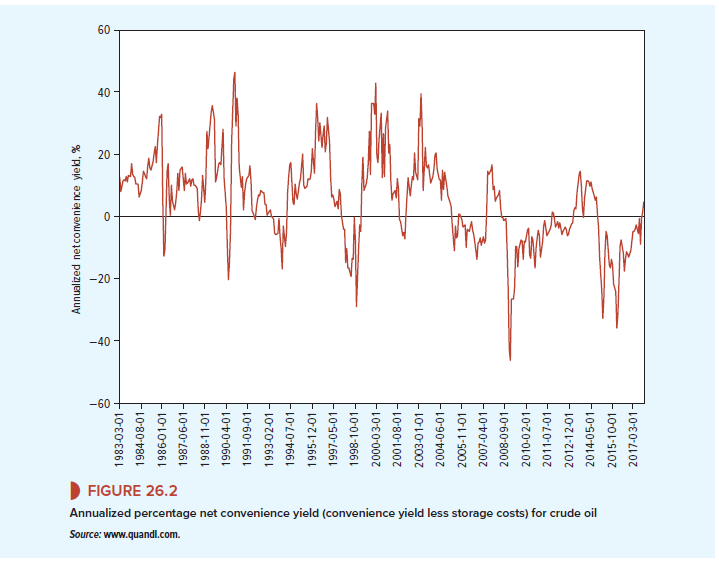

Usually, you can’t observe storage cost or convenience yield, but you can infer the difference between them by comparing spot and futures prices. This difference—that is, convenience yield less storage cost—is called net convenience yield (net convenience yield = convenience yield – storage costs).

EXAMPLE 26.2 ● Calculating Net Convenience Yield

In December 2017, the spot price of crude oil was $57.57 a barrel and the six-month futures price was $56.91 per barrel. The interest rate was about 1.2% for six months. Thus

So net convenience yield was positive, that is, net convenience yield = convenience yield – storage costs = .0235 or 2.35% over six months, equivalent to an annual net convenience yield of 4.8%. Evidently the convenience yield from having crude oil in the storage tanks was slightly greater than the storage cost of those inventories.

Figure 26.2 plots the annualized net convenience yield for crude oil since 1983. Notice how much the spread between the spot and futures price can bounce around. When there are shortages or fears of an interruption of supply, traders may be prepared to pay a hefty premium for the convenience of having inventories of crude oil rather than the promise of future delivery. The reverse is true when storage tanks are full to the brim as in 2016.

There is one further complication that we should note. There are some commodities that cannot be stored at all. You cannot easily store electricity, for example. As a result, electricity supplied in, say, six-months’ time is a different commodity from electricity available now, and there is no simple link between today’s price and that of a futures contract to buy or sell at the end of six months. Of course, generators and electricity users will have their own views of what the spot price is likely to be, and the futures price will reveal these views to some extent.

6. More about Forward Contracts

Each day, billions of dollars of futures contracts are bought and sold. This liquidity is possible only because futures contracts are standardized and mature on a limited number of dates each year.

Fortunately, there is usually more than one way to skin a financial cat. If the terms of futures contracts do not suit your particular needs, you may be able to buy or sell a tailor-made forward contract. The main forward market is in foreign currency. We discuss this market in Chapter 27.

It is also possible to enter into a forward interest rate contract. For example, suppose you know that at the end of three months you are going to need a six-month loan. If you are worried that interest rates will rise over the three-month period, you can lock in the interest rate on the loan by buying a forward rate agreement (FRA) from a bank.[9] For example, the bank might sell you a 3-against-9 month (or 3 X 9) FRA at 7%. If, at the end of three months, the six-month interest rate is higher than 7%, then the bank will make up the difference;[10] if it is lower, then you must pay the bank the difference.[11]

6. Homemade Forward Rate Contracts

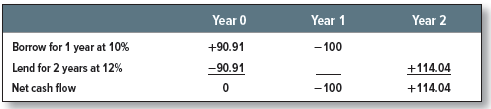

Suppose that you borrow $90.91 for one year at 10% and lend $90.91 for two years at 12%. These interest rates are for loans made today; therefore, they are spot interest rates.

The cash flows on your transactions are as follows:

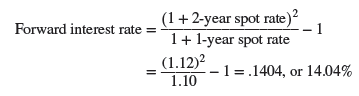

Notice that you do not have any net cash outflow today but you have contracted to pay out money in year 1. The interest rate on this forward commitment is 14.04%. To calculate this forward interest rate, we simply worked out the extra return for lending for two years rather than one:

In our example, you manufactured a forward loan by borrowing short term and lending long. But you can also run the process in reverse. If you wish to fix today the rate at which you borrow next year, you borrow long and lend the money until you need it next year.

24 Jun 2021

23 Jun 2021

25 Jun 2021

24 Jun 2021

24 Jun 2021

24 Jun 2021