Unlike the common or garden bond, a convertible security can change its spots. It starts life as a bond (or preferred stock) but subsequently may turn into common stock. For example, in March 2017, Tesla issued $850 million of 2.375% convertible senior notes due in 2022. Each bond can be converted at any time into 3.0534 shares of common stock. Thus the owner has a five-year option to return the bond to the company and receive 3.0534 shares of common stock in exchange. The number of shares into which each bond can be converted is called the bond’s conversion ratio. The conversion ratio of the Tesla bond is 3.0534.

To receive these shares, the owner of the convertible must surrender bonds with a face value of $1,000. This means that to receive one share, the owner needs to surrender a face amount of $1,000/3.0534 = $327.75. This is the bond’s conversion price. Anybody who bought the bond at $1,000 to convert it into stock paid the equivalent of $327.75 a share, 25% above the stock price at the time of the convertible issue.

You can think of a convertible bond as equivalent to a straight bond plus an option to acquire common stock. When convertible bondholders exercise this option, they do not pay cash; instead they give up their bonds in exchange for shares. If Tesla’s bonds had not been convertible, they would probably have been worth about $870 at the time of issue. The difference between the price of a convertible bond and the price of an equivalent straight bond represents the value that investors place on the conversion option. For example, an investor who paid $1,000 in 2017 for the Tesla convertible would have paid about $1,000 – $870 = $130 for the five-year option to acquire 3.0534 shares.

1. The Value of a Convertible at Maturity

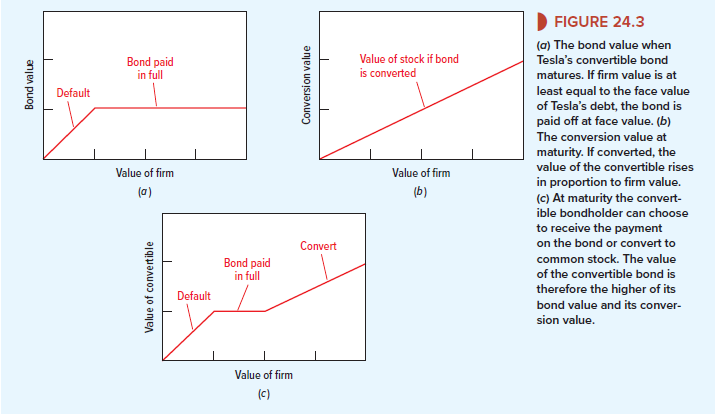

By the time that the Tesla convertible matures, investors need to choose whether to stay with the bond or convert to common stock. Figure 24.3a shows the possible bond values at maturity.[1] Notice that the bond value is simply the face value as long as Tesla does not default. However, if the value of the company’s assets is sufficiently low, the bondholders will receive less than the face value and, in the extreme case that the assets are worthless, they will receive nothing. You can think of the bond value as a lower bound, or “floor,” to the price of the convertible. But that floor has a nasty slope and, when the company falls on hard times, the bond may not be worth much.

Figure 24.3b shows the value of the shares that investors receive if they choose to convert. If Tesla’s assets at that point are worthless, the shares into which the convertible can be exchanged are also worthless. But, as the value of the assets rises, so does the conversion value.

Tesla’s convertible cannot sell for less than its conversion value. If it did, investors would buy the convertible, exchange it rapidly for stock, and sell the stock. Their profit would be equal to the difference between the conversion value and the price of the convertible. Therefore, there are two lower bounds to the price of the convertible: its bond value and its conversion value. Investors will not convert if the convertible is worth more as a bond; they will do so if the conversion value at maturity exceeds the bond value. In other words, the price of the convertible at maturity is represented by the higher of the two lines in Figures 24.3a and b. This is shown in Figure 24.3c.

2. Forcing Conversion

Many issuers of convertible bonds have an option to buy (or call) the bonds back at their face value whenever its stock price is 30% or so above the bond’s conversion price.[2] If the company does announce that it will call the bonds, it makes sense for investors to convert immediately. Thus, a call can force conversion.

3. Why Do Companies Issue Convertibles?

You are approached by an investment banker who is anxious to persuade your company to issue a convertible bond with a conversion price set somewhat above the current stock price. She points out that investors would be prepared to accept a lower yield on the convertible, so that it is “cheaper” debt than a straight bond.[3] You observe that if your company’s stock performs as well as you expect, investors will convert the bond. “Great,” she replies, “in that case, you will have sold shares at a much better price than you could sell them for today. It’s a win-win opportunity.”

Is the investment banker right? Are convertibles “cheap debt”? Of course not. They are a package of a straight bond and an option. The higher price that investors are prepared to pay for the convertible represents the value that they place on the option. The convertible is “cheap” only if this price overvalues the option.

What then of the other argument, that the issue represents a deferred sale of common stock at an attractive price? The convertible gives investors the right to buy stock by giving up a bond.[4] Bondholders may decide to do this, but then again they may not. Thus, issue of a convertible bond may amount to a deferred stock issue. But if the firm needs equity capital, a convertible issue is an unreliable way of getting it.

John Graham and Campbell Harvey surveyed companies that had seriously considered issuing convertibles. In 58% of the cases, management considered convertibles an inexpensive way to issue “delayed” common stock. Forty-two percent of the firms viewed convertibles as less expensive than straight debt.[5] Taken at their face value, these arguments don’t make sense. But we suspect that these phrases encapsulate some more complex and rational motives.

Notice that convertibles tend to be issued by smaller and more speculative firms. These issues are almost invariably unsecured and generally subordinated. Now put yourself in the position of a potential investor. You are approached by a firm with an untried product line that wants to issue some junior unsecured debt. You know that if things go well, you will get your money back, but if they do not, you could easily be left with nothing. Since the firm is in a new line of business, it is difficult to assess the chances of trouble. Therefore, you don’t know what the fair rate of interest is. Also, you may be worried that once you have made the loan, management will be tempted to run extra risks. It may take on additional senior debt, or it may decide to expand its operations and go for broke on your money. In fact, if you charge a very high rate of interest, you could be encouraging this to happen.

What can management do to protect you against a wrong estimate of the risk and to assure you that its intentions are honorable? In crude terms, it can give you a piece of the action. You don’t mind the company running unanticipated risks as long as you share in the gains as well as the losses.[6] Convertible securities make sense whenever it is unusually costly to assess the risk of debt or whenever investors are worried that management may not act in the bondholders’ interest.[7]

The relatively low coupon rate on convertible bonds may also be a convenience for rapidly growing firms facing heavy capital expenditures.[8] They may be willing to provide the conversion option to reduce immediate cash requirements for debt service. Without that option, lenders might demand extremely high (promised) interest rates to compensate for the probability of default. This would not only force the firm to raise still more capital for debt service but also increase the risk of financial distress. Paradoxically, lenders’ attempts to protect themselves against default may actually increase the probability of financial distress by increasing the burden of debt service on the firm.

4. Valuing Convertible Bonds

We have seen that a convertible bond is equivalent to a package of a bond and an option to buy stock. This means that the option-valuation models that we described in Chapter 21 can also be used to value the option to convert. We don’t want to repeat that material here, but we should note three wrinkles that you need to look out for when valuing a convertible:

- Dividends. If you hold the common stock, you may receive dividends. The investor who holds an option to convert into common stock misses out on these dividends. In fact, the convertible holder loses out every time a cash dividend is paid because the dividend reduces the stock price and thus reduces the value of the conversion option. If the dividends are high enough, it may even pay to convert before maturity to capture the extra income. We showed how dividend payments affect option value in Section 21-5.

- Dilution. The second complication arises because conversion increases the number of outstanding shares. Therefore, exercise means that each shareholder is entitled to a smaller proportion of the firm’s assets and profits.[9] This problem of dilution never arises with traded options. If you buy an option through an option exchange and subsequently exercise it, you have no effect on the number of shares outstanding.

- Changing bond value. When investors convert to shares, they give up their bond. The exercise price of the option is therefore the value of the bond that they are relinquishing. But this bond value is not constant. If the bond value at issue is less than the face value (and it usually is less), it is likely to change as maturity approaches. Also, the bond value varies as interest rates change and as the company’s credit standing changes. If there is some possibility of default, investors cannot even be certain of what the bond will be worth at maturity. In Chapter 21, we did not get into the complication of uncertain exercise prices.

5. A Variation on Convertible Bonds: The Bond-Warrant Package

Instead of issuing a convertible bond, companies sometimes sell a package of straight bonds and warrants. Warrants are simply long-term call options that give the investor the right to buy the firm’s common stock. For example, in 2017 the German chemical giant, BASF, placed a $600 million package of bonds and warrants maturing in 2023. The exercise price of the warrants was set at 112.45 euros, 25% above the price of the stock at the time of issue.

Convertible bonds consist of a package of a straight bond and an option. An issue of bonds and warrants also contains a straight bond and an option. But there are some differences:

- Warrants are usually issued privately. Packages of bonds with warrants tend to be more common in private placements. By contrast, most convertible bonds are issued publicly.

- Warrants can be detached. When you buy a convertible, the bond and the option are bundled together. You cannot sell them separately. This may be inconvenient. If your tax position or attitude to risk inclines you to bonds, you may not want to hold options as well. Warrants are sometimes also “nondetachable,” but usually you can keep the bond and sell the warrant.

- Warrants are exercised for cash. When you convert a bond, you simply exchange your bond for common stock. When you exercise warrants, you generally put up extra cash, though occasionally you have to surrender the bond or can choose to do so. This means that the bond-warrant package and the convertible bond have different effects on the company’s cash flow and on its capital structure.

- A package of bonds and warrants may be taxed differently. There are some tax differences between warrants and convertibles. Suppose that you are wondering whether to issue a convertible bond at 100. You can think of this convertible as a package of a straight bond worth, say, 90 and an option worth 10. If you issue the bond and option separately, the IRS will note that the bond is issued at a discount and that its price will rise by 10 points over its life. The IRS will allow you, the issuer, to spread this prospective price appreciation over the life of the bond and deduct it from your taxable profits. The IRS will also allocate the prospective price appreciation to the taxable income of the bondholder. Thus, by issuing a package of bonds and warrants rather than a convertible, you may reduce the tax paid by the issuing company and increase the tax paid by the investor.

- Warrants may be issued on their own. Warrants do not have to be issued in conjunction with other securities. Often they are used to compensate investment bankers for underwriting services. Many companies also give their executives long-term options to buy stock. These executive stock options are not usually called warrants, but that is exactly what they are. Companies can also sell warrants on their own directly to investors, though they rarely do so.

6. Innovation in the Bond Market

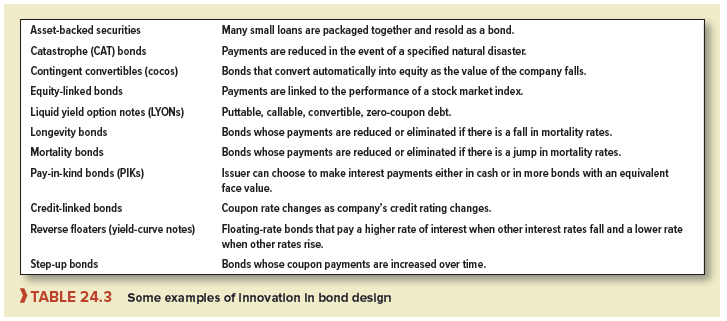

Domestic bonds and eurobonds, fixed- and floating-rate bonds, coupon bonds and zeros, callable and puttable bonds, straight bonds and convertible bonds—you might think that this would give you as much choice as you need. Yet almost every day some new type of bond seems to be issued. Table 24.3 lists some of the more interesting bonds that have been invented in recent years. Earlier in the chapter, we described asset-backed securities, and in Chapter 26, we discuss catastrophe bonds whose payoffs are linked to the occurrence of natural disasters.

Some financial innovations appear to serve little or no economic purpose; they may flower briefly but then wither. For example, toward the end of the 1990s in the United States, there was a bout of new issues of floating-price convertibles, or, as they were more commonly called, death-spiral, or toxic, convertibles. When death-spiral convertibles are issued, the conversion price is set below the current stock price. Moreover, each bond is convertible not into a fixed number of shares but into shares with a fixed value. Therefore, the more the share price falls, the more shares that the convertible bondholder is entitled to. With a normal convertible, the value of the conversion option falls whenever the value of the firm’s assets falls; so the convertible holder shares some of the pain with the stockholders. With a death-spiral convertible, the holder is entitled to shares with a fixed value, so the entire effect of the decrease in the asset price falls on the common stockholders. Death-spiral convertibles were issued largely by companies that were already in desperate straits, and, when the issuers failed to recover, the toxic chicken came home to roost. After the initial flurry of issues in the United States, death-spiral convertibles seem now to have been consigned to the garbage heap of unsuccessful innovations.

Many other innovations seem to have a more obvious purpose. Here are some important motives for creating new securities:

- Investor choice. Sometimes new financial instruments are created to widen investor choice. Economists refer to such securities as helping to “complete the market.” This was the idea behind the 2013 issue of nearly $180 million of mortality, or death bonds by the French insurance company SCOR. One of the big risks for a life insurance company is a pandemic or other disaster that results in a sharp increase in the death rate. SCOR’s bond, therefore, offers investors a higher interest rate for taking on some of that risk. Holders of the bonds will lose their entire investment if U.S. death rates for two consecutive years are unusually high. Mortality bonds widen investor choice. They allow insurance companies to protect themselves against adverse changes in mortality and they spread the risk widely around the market.

- Government regulation and tax. Merton Miller has described new government regulations and taxes as the sand in the oyster that stimulates the design of new types of security. For example, we have already seen how the eurobond market was a response to the U.S. government’s imposition of a tax on purchases of foreign securities.

Asset-backed securities provide another instance of a market that was encouraged by regulation. To reduce the likelihood of failure, banks are obliged to finance part of their loan portfolio with equity capital. Many banks were able to reduce the amount of capital that they needed to hold by packaging up their loans or credit card receivables and selling them off as bonds. Bank regulators have worried about this. They think that banks may be tempted to sell off their riskiest loans and to keep their safest ones. They have therefore introduced new regulations that will link the capital requirement to the riskiness of the loans.

- Reducing agency costs. We have already seen how convertible bonds may reduce agency cost. Here is another example. At the turn of the century, investors were worried by the huge spending plans of telecom companies. So when Deutsche Telecom, the German telecom giant, decided to sell $15 billion of bonds in 2000, it agreed to increase the coupon rate on the bonds by 50 basis points if ever its bonds were downgraded to below investment grade by Moody’s or Standard & Poor’s. Deutsche Telecom’s credit- linked bonds protected investors against possible future attempts by the company to exploit existing bondholders by loading on more debt.

Here is yet another example where bond design can help to solve agency problems. Bankers love to borrow rather than issue equity. The problem is that when banks encounter heavy weather, the shareholders may refuse to come to the rescue with more capital. One suggested remedy is for the banks to issue contingent convertible bonds (or cocos). These are bonds that convert automatically into equity if the bank hits trouble. For example, in 2016 the Spanish bank, BBVA, issued €500 million of perpetual cocos. If BBVA’s capital falls below a specified level, the cocos reduce the bank’s leverage by changing into equity.

Dreaming up these new financial instruments is only half the battle. The other problem is to produce them efficiently. Think, for example, of the problems of packaging together several hundred million dollars’ worth of credit card receivables and allocating the cash flows to a diverse group of investors. That requires good computer systems. The deal also needs to be structured so that, if the issuer goes bankrupt, the receivables will not be part of the bankruptcy estate. That depends on the development of legal structures that will stand up in the event of a dispute.

Attractive component of content. I just stumbled upon your blog and in accession capital to assert that I get actually loved account your weblog posts. Anyway I will be subscribing for your feeds and even I fulfillment you get admission to consistently fast.