If the manufacturer decides to go ahead with a licensing venture, the profitability analysis will also provide guidelines for negotiating the licensing agreement. The first task is to select the prospective licensee in the target country.

1. Selecting the Prospective Licensee

The screening process used to select a licensee candidate resembles that used to select a foreign distributor, as described in Chapter 3. The process has four steps: (1) determining the manufacturer’s licensee profile, (2) sourcing licensee prospects, (3) evaluating and comparing licensee prospects, and (4) selecting the most appropriate licensee candidate.

The licensee profile lists all the attributes that the manufacturer would like to get in its licensee for a given target market. The profile, therefore, is an ideal construct that reflects the manufacturer’s objectives and its profitability analysis of the prospective licensing venture. It specifies the desired licensee qualifications relating to product line, technical competence, production facilities, quality control, distribution system, general management, business reputation and honesty, financial strength, size, ownership, compatibility as a working partner, and any other attributes that the manufacturer considers important to the success of the venture. The manufacturer should go beyond a simple listing of qualifications by rating them in importance, because it will almost certainly be impossible to find a live licensee candidate who matches the profile on all points.

The manufacturer can obtain the names of prospective licensees from several sources. Probably the most common source is the unsolicited inquiry from a foreign company. Indeed, many manufacturers have responded only to unsolicited inquiries in establishing licensing arrangements. Given the nonselective character of unsolicited inquiries, however, the manufacturer should also undertake an active search for licensing prospects who will satisfy his licensee profile. If the manufacturer is currently exporting to the target country, his agents, distributors, or customers may be good licensing prospects, or may supply leads to prospects. Names may also be obtained from the advertisements of foreign companies in trade publications; representatives of industry, banks, and governments in both the home and target countries; promotion by the manufacturer in trade publications and other media; and international trade fairs and other gatherings of businesspeople.

To evaluate licensee prospects, the manufacturer needs to get information on them. As in the case of distributor prospects, the most direct way is to write a letter to each prospect asking about his interest in a licensing agreement and about his qualifications. Evaluation of the responses to this letter, checks with banks and other references, and additional information obtained from private and government sources may then be supplemented by a second letter to the most promising candidates. However, the manufacturer is well advised to make the final selection only after personal visits to the best prospects. If the manufacturer has done a systematic screening job, it can be reasonably confident that it has found a good candidate who will justify the time and expense of negotiating a licensing agreement.

2. The Negotiation Process

Although international licensing negotiations have been conducted entirely by correspondence, it is always advisable to have face-to-face negotiations. Several negotiating sessions are the rule rather than the exception, and the average negotiations (including the preparation of legal documents) last six months to one year. Since the negotiations are between nationals of different countries, they are exposed to all the perils of cross-cultural communication. Even when both parties can obviously benefit each other, negotiations may collapse because of misunderstanding and distrust engendered by cultural pitfalls.8

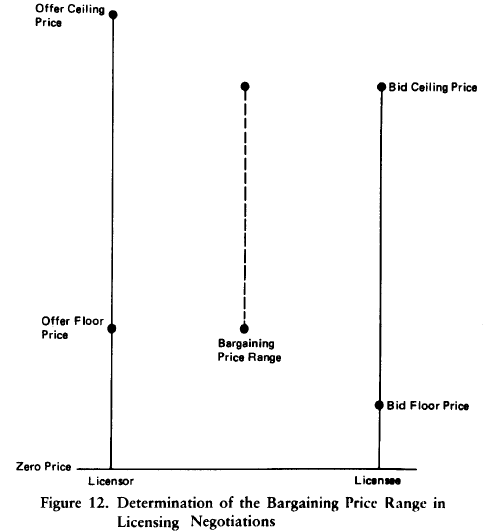

So many individual points must be settled in licensing negotiations that the ensuing agreement will most probably be unique. Several of these points are identified in the next subsection. In this subsection, however, we shall describe the negotiating process in terms of a normative model (Figure 12) that focuses on the determination of the price of the manufacturer’s “technology package.” (The term “technology package” embraces all industrial property rights, technical assistance, and any other assets or services supplied to the licensee by the licensor under an agreement.)

The model postulates that the prospective licensor enters negotiations with a range of possible offer prices for a given technology package while the prospective licensee enters negotiations with a range of possible bid prices. The overlapping of these two ranges determines the bargaining price range.

The licensor’s offer price range is established by his floor and ceiling prices. The offer floor price is the sum of the licensor’s opportunity costs and the costs of transferring the technology package to the licensee. Clearly, the licensor will not accept a price below this floor, because to do so would cause him actual or prospective cash loss. The offer ceiling price is the licensor’s estimation of the value of the technology package to the licensee, that is, how much the use of the technology package would increase the licensee’s net cash flow (profit contribution) over the agreement. Although the licensor, like any seller, would like to get as much as he can for his technology package, he cannot rationally expect to get more than its value to the licensee. To make a good estimate of this value, the licensor needs to know the sales potential of the licensed product in the target market.

On the other side, the licensee’s bid price range is determined by bis floor and ceiling prices. The bid floor price is the licensee’s estimate of the licensor’s transfer costs. (The licensee ignores the licensor’s opportunity costs and, in any event, does not have the information to estimate them.) The licensee cannot rationally expect to get the technology package for less than its transfer costs. The bid ceiling price is the lowest of three values: (1) the incremental cash flow the licensee would obtain from the use of the technology package, (2) the cost of the same or similar technology package from another supplier, and (3) the cost of developing the technology package on his own.9 Under no circumstances would the licensee be willing to pay more than the expected incremental cash flow. It is almost certain that the licensee’s full cost of duplicating the technology package would exceed the other two values. (Duplication would also take much more time than acquiring the package under license.) When the licensee can obtain the technology package from more than one source, the bid ceiling price will usually be determined, therefore, by the lowest alternative offer price. The licensor must at least meet this price if he is to negotiate an agreement.

The licensor’s floor price and the licensee’s ceiling price together determine the bargaining range in the negotiations, as shown in Figure 12. The negotiated price will be at a point on this range.10

The price or compensation to be received for the technology package is not the only issue to be resolved in licensing negotiations. Two other key issues are the content of the technology package itself (the mix of patents, trademarks, know-how, and services), and the use conditions of the package. During the course of negotiations, therefore, the opening bargaining price range will shift with negotiated changes in the technology package and use conditions. (New information and new circumstances that affect the behavior of either party can also cause shifts in the bargaining range.) The negotiation process, therefore, is likely to encompass a sequence of bargaining price ranges over time as well as bargaining within each range at a particular time.

Licensing negotiations can become very complex, because the many elements that make up the three groups of issues may be combined in any number of ways. This flexibility generates many trade-offs that facilitate a final agreement. The technology price, for instance, may be raised or lowered by changes in the technology package or its use conditions. Moreover, the compensation mix is also variable, so that, say, a lower royalty rate may be traded off against lump-sum payments, minimum annual royalties, service fees, equity, and other forms of compensation. Flexibility in th compensation mix may be critical to the success of negotiations when a royalty rate ceiling is imposed by the host government or when the licensee insists on a “conventional rate.” In sum, licensing negotiations are open- ended in several directions.

Our discussion of the negotiating process indicates that the licensor can negotiate more effectively when he has made a profitability analysis of the proposed licensing venture. For then he will better know his objectives, the value of his technology package to the licensee, and the trade-offs among the many elements of a licensing agreement. Evidently, the stronger the licensor’s bargaining leverage, the closer the final negotiated price will be to the licensee’s bid ceiling price. Conversely, the weaker the licensor’s bar-gaining leverage, the closer the final price will be to his offer floor price. But the actual compensation from a licensing agreement will be completely determinable only at the conclusion of the agreement, some years into the future.

This last observation points to the risks assumed by both parties to a licensing agreement. Terms must be negotiated before the value of the technology package to the recipient can be ascertained. The costs and income of the two parties are contingent on the other’s performance over the agreement’s life, as well as on the market and other external factors. The licensor, therefore, must assess both the business risks and the political risks of a proposed licensing venture.

3. The Licensing Contract

The successful conclusion of negotiations is marked by the signing of a licensing contract.11 A licensing contract has the following elements:

Technology Package

Definition/description of the licensed industrial property (patents, trademarks, know-how).

Know-how to be supplied and its method of transfer.

Supply of raw materials, equipment, and intermediate goods.

Use Conditions

Field of use of licensed technology.

Territorial rights for manufacture and sale.

Sublicensing rights.

Safeguarding trade secrets.

Responsibility for defense/infringement action on patents and trademarks.

Exclusion of competitive products.

Exclusion of competitive technology.

Maintenance of product standards.

Performance requirements.

Rights of licensee to new products and technology.

Reporting requirements.

Auditing/inspection rights of licensor.

Reporting requirements of licensee.

Compensation

Currency of payment.

Responsibilities for payment of local taxes.

Disclosure fee.

Running royalties.

Minimum royalties.

Lump-sum royalties.

Technical-assistance fees.

Sales to and/or purchases from licensee.

Fees for additional new products.

Grantback of product improvements by licensee.

Other compensation.

Other Provisions

Contract law to be followed.

Duration and renewal of contract.

Cancellation/termination provisions.

Procedures for the settlement of disputes.

Responsibility for government approval of the license agreement.

Three of these elements deserve some comment, namely, territorial rights, performance requirements, and the settlement of disputes.

Territorial Rights. The licensor’s ownership of patent and trademark rights in the target country is the legal basis for an exclusive license that gives manufacturing and sales rights only to the licensee in that country. Under an exclusive license, the licensor agrees not to allow the use of the technology package by himself or another company in the same territory and field. Whether or not a licensor should grant an exclusive license depends on his market entry strategy and on his bargaining power with a prospective licensee. To illustrate, a licensor may want to grant a nonexclusive license in order to be free to license other companies or use the rights and knowhow on his own in the target country at a later time. In contrast, the licensee usually presses for an exclusive license that will keep out the licensor or other licensees. Quite commonly, a good licensing candidate may refuse to assume the responsibilities of an agreement unless he is granted exclusive rights.

An exclusive license by itself does not prevent the licensee from selling outside the exclusive territory. As observed earlier, patent and trademark rights are limited to a given national jurisdiction. Consequently, whether or not a licensor can limit his licensee’s rights to sell outside the target country depends on government policy and laws in that country as well as on laws governing restrictive business practices in his own country. If a licensee in country A wants to export licensed products to country B, where the licensor also holds industrial property rights, then the import of that product would infringe on the licensor’s rights in country B. Hence there would be no need to include a provision in the licensing contract prohibiting the export of the licensed product from country A to country B.

Suppose the licensor does not have industrial property rights in country B, as is always true with trade secrets. In that case he can control the export of the licensed product from country A to country B only through contractual arrangements with his licensee in country A. But now comes the rub. In many countries, export limitations are not allowed in licensing agreements, because the host government wants to increase exports of industrial products. Furthermore, American manufacturers have to worry about U.S. antitrust laws that question export limitations because they may restrain competition in U.S. trade. Inability to control a licensee’s exports may carry such great opportunity costs for the licensor as to doom any licensing venture. The obvious way to avoid legal complications is to grant only nonexclusive licenses, but this policy can cut the value of the licensor’s technology to prospective licensees, as well as create unacceptable opportunity costs.

Performance Requirements. The success of a licensing venture depends on the licensee’s ability and willingness to manufacture the licensed product to agreed quality standards and to exploit fully its sales potential in the target market. This dependence is particularly acute with an exclusive licensing agreement. To protect his interests, therefore, the licensor needs to include performance provisions in the contract with respect to both production and sales. Penalties for the licensee’s failure to meet the stipulated performance requirements can include fees, liquidated damages, or termination of the contract.

As for production, quality control may be exercised by the licensor in several ways: an agreed standard of quality; the right of the licensor to inspect the licensee’s operations and make product tests; the use of the licensor’s own engineers to supervise the licensee’s production; the use of specified raw materials, equipment, and components; and so on. Apart from suffering damage to his reputation, the licensor may lose his trader- mark rights in the target country if the licensee fails to meet the usual quality standards.

As for sales, the licensor may specify a minimum volume of sales or minimum promotion and other marketing expenditures. But the most common way to motivate the licensee’s selling efforts is the requirement of minimum royalty payments. In this way, the licensor is assured of a certain royalty income regardless of the sales of the licensed product. Minimum royalty payments are especially desirable in exclusive licensing ventures.

Settlement of Disputes. The terms of a licensing contract should be explicit, but at the same time, they should be flexible enough that both parties can execute them. Nonetheless, disputes will arise from time to time. In most instances, they can be settled by reference to the written contract and by talking over differences. But with some disputes, settlement may require use of external procedures, which should be spelled out in the contract.

In general, litigation should be avoided by the licensor, not only because it is costly and time-consuming, but also because jurisdiction may be established in the foreign country even though the contract specifies that the governing law is that of the licensor’s country. The best way to avoid litigation of disputes is to provide for arbitration that is binding on both parties. The arbitration clause in the contract should state the applicable arbitration rules (the most common are those of the American Arbitration Association and the International Chamber of Commerce) or name the arbitration tribunal.

4. Working with the Licensee

The licensing contract marks the conclusion of formal negotiations, but it is only the start of the licensing venture. Both parties must now cooperate in building that venture so that it can meet their shared expectations. In most instances, the licensee will need continuing technical assistance from the licensor, who in turn has an obvious interest in helping the licensee exploit the sales potential of the licensed product in the target market. A licensing venture, therefore, should be regarded as a nonequity joint venture that combines the strengths of the two parties in the pursuit of common goals. When a licensor views his obligations to the licensee as ending with an initial transfer of industrial property rights and know-how, he is using licensing as a source of income, not as an instrument to build a market position in the target country.

This chapter has focused on licensing as a primary entry mode, that is, the use of licensing as a full alternative to exporting or equity investment. But licensing is an extremely flexible vehicle that may be easily combined with other entry modes to form mixed entry modes. Indeed, licensing is used most frequently in association with equity joint or sole manufacturing ventures. For instance, in recent years more than three-quarters of the royalties and licensing fees received by U.S. companies have been from affiliated foreign firms. In fact, the line dividing licensing from direct investment is sometimes hard to distinguish. A licensing contract that arranges for compensation in the form of equity in the licensee company or gives the licensor an option to invest in that company can transform a licensing venture into an equity joint venture. Also, as has been noted, licensing agreements may involve the sale of intermediate and other products by the licensor to the licensee or, conversely, the sale of finished products by the licensee to the licensor.

To conclude, licensing may be combined with other entry modes to create a mixed entry mode that is superior to any of its constituents. And a pure licensing venture can grow in time into an equity joint venture or stimulate other international business arrangements. These two features alone ensure that licensing will always be an important element in the foreign market entry strategies of many manufacturers.

Source: Root Franklin R. (1998), Entry Strategies for International Markets, Jossey-Bass; 2nd edition.

Very excellent information can be found on website.