Suppose you bought a new car for $20,000, drove it 100 miles, and then decided you really didn’t want it. There was nothing wrong with the car—it performed beautifully and met all your expectations. You simply felt that you could do just as well without it and would be better off saving the money for other things. So you decide to sell the car. How much should you expect to get for it? Probably not more than $16,000—even though the car is brand new, has been driven only 100 miles, and has a warranty that is transferable to a new owner. And if you were a prospective buyer, you probably wouldn’t pay much more than $16,000 yourself.

Why does the mere fact that the car is second-hand reduce its value so much? To answer this question, think about your own concerns as a prospective buyer. Why, you would wonder, is this car for sale? Did the owner really change his or her mind about the car just like that, or is there something wrong with it? Is this car a “lemon”?

Used cars sell for much less than new cars because there is asymmetric information about their quality: The seller of a used car knows much more about the car than the prospective buyer does. The buyer can hire a mechanic to check the car, but the seller has had experience with it and will know more about it. Furthermore, the very fact that the car is for sale indicates that it may be a “lemon”—why sell a reliable car? As a result, the prospective buyer of a used car will always be suspicious of its quality—and with good reason.

The implications of asymmetric information about product quality were first analyzed by George Akerlof and go far beyond the market for used cars. The markets for insurance, financial credit, and even employment are also characterized by asymmetric information about product quality. To understand the implications of asymmetric information, we will start with the market for used cars and then see how the same principles apply to other markets.

1. The Market for Used Cars

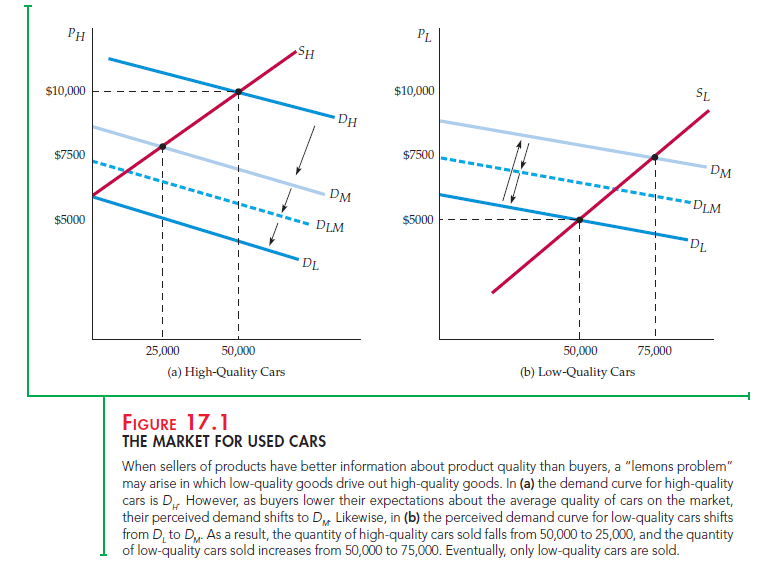

Suppose two kinds of used cars are available—high-quality cars and low-quality cars. Also suppose that both sellers and buyers can tell which kind of car is which. There will then be two markets, as illustrated in Figure 17.1. In part (a), SH is the supply curve for high-quality cars, and DH is the demand curve. Similarly, SL and DL in part (b) are the supply and demand curves for low-quality cars. For any given price, SH lies to the left of SL because owners of high-quality cars are more reluctant to part with them and must receive a higher price to do so. Similarly, DH is higher than DL because buyers are willing to pay more to get a high-quality car. As the figure shows, the market price for high-quality cars is $10,000, for low-quality cars $5000, and 50,000 cars of each type are sold.

In reality, the seller of a used car knows much more about its quality than a buyer does. (Buyers discover the quality only after they buy a car and drive it for a while.) Consider what happens, then, if sellers know the quality of cars, but buyers do not. Initially, buyers might think that the odds are 50-50 that a car will be high quality. Why? Because when both sellers and buyers know the quality, 50,000 cars of each type are sold. When making a purchase, buyers therefore view all cars as “medium quality,” in the sense that there is an equal chance of getting a high-quality or a low-quality car. (Of course, after buying the car and driving it for a while, they will learn its true quality.) The demand for cars perceived to be medium quality, denoted by DM in Figure 17.1, is below Dh but above DL. As the figure shows, these medium-quality cars will sell for about $7500 each. However, fewer high-quality cars (25,000) and more low-quality cars (75,000) will now be sold.

As consumers begin to realize that most cars sold (about three-fourths of the total) are low quality, their perceived demand shifts. As Figure 17.1 shows, the new perceived demand curve might be DLM, which means that, on average, cars are thought to be of low to medium quality. However, the mix of cars then shifts even more heavily to low quality. As a result, the perceived demand curve shifts further to the left, pushing the mix of cars even further toward low quality. This shifting continues until only low-quality cars are sold. At that point, the market price would be too low to bring forth any high-quality cars for sale, so consumers correctly assume that any car they buy will be low quality. As a result, the only relevant demand curve will be DL.

The situation in Figure 17.1 is extreme. The market may come into equilibrium at a price that brings forth at least some high-quality cars. But the fraction of high-quality cars will be smaller than it would be if consumers could identify quality before making the purchase. That is why you should expect to sell your brand new car, which you know is in perfect condition, for much less than you paid for it. Because of asymmetric information, low-quality goods drive high-quality goods out of the market. This phenomenon, which is sometimes referred to as the lemons problem, is an important source of market failure. It is worth emphasizing:

2. Implications of Asymmetric Information

Our used cars example shows how asymmetric information can result in market failure. In an ideal world of fully functioning markets, consumers would be able to choose between low-quality and high-quality cars. While some will choose low-quality cars because they cost less, others will prefer to pay more for high- quality cars. Unfortunately, consumers cannot in fact easily determine the quality of a used car until after they purchase it. As a result, the price of used cars falls, and high-quality cars are driven out of the market.

Market failure arises, therefore, because there are owners of high-quality cars who value their cars less than potential buyers of high-quality cars. Both parties could enjoy gains from trade, but, unfortunately, buyers’ lack of information prevents this mutually beneficial trade from occurring.

ADVERSE SELECTION Our used car scenario is a simplified illustration of an important problem that affects many markets—the problem of adverse selection. Adverse selection arises when products of different qualities are sold at a single price because buyers or sellers are not sufficiently informed to determine the true quality at the time of purchase. As a result, too much of the low-quality product and too little of the high-quality product are sold in the marketplace. Let’s look at some other examples of asymmetric information and adverse selection. In doing so, we will also see how the government or private firms might respond to the problem.

THE MARKET FOR INSURANCE Why do people over age 65 have difficulty buying medical insurance at almost any price? Older people do have a much higher risk of serious illness, but why doesn’t the price of insurance rise to reflect that higher risk? Again, the reason is asymmetric information. People who buy insurance know much more about their general health than any insurance company can hope to know, even if it insists on a medical examination. As a result, adverse selection arises, much as it does in the market for used cars. Because unhealthy people are more likely to want insurance, the proportion of unhealthy people in the pool of insured people increases. This forces the price of insurance to rise, so that more healthy people, aware of their low risks, elect not to be insured. This further increases the proportion of unhealthy people among the insured, thus forcing the price of insurance up more. The process continues until most people who want to buy insurance are unhealthy. At that point, insurance becomes very expensive, or—in the extreme—insurance companies stop selling the insurance.

Adverse selection can make the operation of insurance markets problematic in other ways. Suppose an insurance company wants to offer a policy for a particular event, such as an auto accident that results in property damage. It selects a target population—say, men under age 25—to whom it plans to market this policy, and it estimates that the probability of an accident for people in this group is .01. However, for some of these people, the probability of having an accident is much less than .01; for others, it is much higher than .01. If the insurance company cannot distinguish between high- and low-risk men, it will base the premium on the average accident probability of .01. What will happen? Those people with low probabilities of having an accident will choose not to insure, while those with high probabilities of an accident will purchase the insurance. This in turn raises the accident probability among those who choose to be insured above .01, forcing the insurance company to raise its premium. In the extreme, only those who are likely to be in an accident will choose to insure, making it impractical to sell insurance.

One solution to the problem of adverse selection is to pool risks. For health insurance, the government might take on this role, as it does with the Medicare program. By providing insurance for all people over age 65, the government eliminates the problem of adverse selection. Likewise, insurance companies will try to avoid or at least reduce the adverse selection problem by offering group health insurance policies at places of employment. By covering all workers in a firm, whether healthy or sick, the insurance company spreads risks and thereby reduces the likelihood that large numbers of high-risk individuals will purchase insurance.

THE MARKET FOR CREDIT By using a credit card, many of us borrow money without providing any collateral. Most credit cards allow the holder to run a debt of several thousand dollars, and many people hold several credit cards. Credit card companies earn money by charging interest on the debit balance. But how can a credit card company or bank distinguish high-quality borrowers (who pay their debts) from low-quality borrowers (who don’t)? Clearly, borrowers have better information—i.e., they know more about whether they will pay than the lender does. Again, the lemons problem arises. Low-quality borrowers are more likely than high-quality borrowers to want credit, which forces the interest rate up, which increases the number of low-quality borrowers, which forces the interest rate up further, and so on.

In fact, credit card companies and banks can, to some extent, use computerized credit histories, which they often share with one another, to distinguish low-quality from high-quality borrowers. Many people, however, think that computerized credit histories invade their privacy. Should companies be allowed to keep these credit histories and share them with other lenders? We can’t answer this question for you, but we can point out that credit histories perform an important function: They eliminate, or at least greatly reduce, the problem of asymmetric information and adverse selection—a problem that might otherwise prevent credit markets from operating. Without these histories, even the creditworthy would find it extremely costly to borrow money.

3. The Importance of Reputation and Standardization

Asymmetric information is also present in many other markets. Here are just a few examples:

- Retail stores: Will the store repair or allow you to return a defective product? The store knows more about its policy than you do.

- Dealers of rare stamps, coins, books, and paintings: Are the items real or counterfeit? The dealer knows much more about their authenticity than you do.

- Roofers, plumbers, and electricians: When a roofer repairs or renovates the roof of your house, do you climb up to check the quality of the work?

- Restaurants: How often do you go into the kitchen to check if the chef is using fresh ingredients and obeying health laws?

In all these cases, the seller knows much more about the quality of the product than the buyer does. Unless sellers can provide information about quality to buyers, low-quality goods and services will drive out high-quality ones, and there will be market failure. Sellers of high-quality goods and services, therefore, have a big incentive to convince consumers that their quality is indeed high. In the examples cited above, this task is performed largely by reputation. You shop at a particular store because it has a reputation for servicing its products; you hire particular roofers or plumbers because they have reputations for doing good work; you go to a particular restaurant because it has a reputation for using fresh ingredients and nobody you know has become sick after eating there. Amazon and other online vendors use another model to maintain their reputation. They allow customers to rate and comment on products. The rating and commenting feature reduces the lemons problem by giving customers more information and motivating vendors to uphold their end of the bargain.

Sometimes, however, it is impossible for a business to develop a reputation. For example, because most of the customers of highway diners or motels go there only once or infrequently, the businesses have no opportunity to develop reputations. How, then, can they deal with the lemons problem? One way is standardization. In your hometown, you may not prefer to eat regularly at McDonald’s. But a McDonald’s may look more attractive when you are driving along a highway and want to stop for lunch. Why? Because McDonald’s provides a standardized product: The same ingredients are used and the same food is served in every McDonald’s anywhere in the country. Who knows? Joe’s Diner might serve better food, but at least you know exactly what you will be buying at McDonald’s.

Source: Pindyck Robert, Rubinfeld Daniel (2012), Microeconomics, Pearson, 8th edition.

There is noticeably a bundle to know about this. I assume you made certain nice points in features also.