Retail firms may be independently owned, chain-owned, franchisee-operated, leased departments, owned by manufacturers or wholesalers, or consumer-owned.

Although retailers are primarily small (three-quarters of all stores are operated by firms with one outlet and more than one-half of all firms have two or fewer paid employees), there are also very large retailers. The five leading U.S.-based retailers annually total $700 billion in U.S. sales alone and employ about 3 million people in the United States. Ownership opportunities abound. According to the U.S. Census Bureau (www.census.gov), women own one million retail firms, African Americans (men and women) 120,000 retail firms, Hispanic Americans (men and women) 185,000 retail firms, and Asian Americans (men and women) 200,000 retail firms.

Each ownership format serves a marketplace niche, if the strategy is executed well:

- Independent retailers capitalize on a highly targeted customer base and please shoppers in a friendly, informal way. Word-of-mouth communication is important. These retailers should not try to serve too many customers or enter into price wars.

- Chain retailers benefit from their widely known image and from economies of scale and mass promotion possibilities. They should maintain their image chainwide and not be inflexible in adapting to changes in the marketplace.

- Franchisors have strong geographic coverage—due to franchisee investments—and the motivation of franchisees as owner-operators. They should not get bogged down in policy disputes with franchisees or charge excessive royalty fees.

- Leased departments enable store operators and outside parties to join forces and enhance the shopping experience, while sharing expertise and expenses. They should not hurt the image of the store or place too much pressure on the lessee to generate store traffic.

- A vertically integrated channel gives a firm greater control over sources of supply, but it should not provide consumers with too little choice of products or too few outlets.

- Cooperatives provide members with cost savings due to pooled purchasing and joint ownership of a warehouse. They should not expect too much involvement by members or add facilities that raise costs too much.

1. Independent

An independent retailer owns one retail unit. We estimate that there are 2.3 million independent U.S. retailers—accounting for about one-quarter of total store sales. Seventy percent of independents are run by the owners and their families; and those firms generate just 3 percent of U.S. store sales (averaging under $100,000 in annual revenues) and have no paid workers (there is no payroll).

The high number of independents is associated with the ease of entry into the marketplace, due to low capital requirements and no, or relatively simple, licensing provisions for many small retail firms. The investment per worker in retailing is usually much lower than for manufacturers, and licensing is pretty routine. Each year, tens of thousands of new retailers, mostly independents, open in the United States.

The ease of entry—which leads to intense competition—is a big factor in the high rate of failures among newer firms. One-third of new U.S. retailers do not survive the first year, and two-thirds do not continue beyond the third year. Most failures involve independents. Annually, thousands of U.S. retailers (of all sizes) file for bankruptcy protection—besides the thousands of small firms that simply close.2

The U.S. Small Business Administration (SBA) has a Small Business Development Center (SBDC) to assist current and prospective small business owners (www.sba.gov/content/ small-business-development-centers-sbdcs). There are 63 lead SBDCs (at least one in every state) and more than 900 local SBDCs, satellites, and specialty centers. The purpose is to assist “small businesses with financial, marketing, production, organization, engineering, and technical problems and feasibility studies.” Centers offer free counseling, seminars and training sessions, conferences, and information through the Internet, as well as in person and by phone. The SBA also has a lot of free downloadable information at its Web site (www.sba.gov). See Figure 4-2.

COMPETITIVE ADVANTAGES AND DISADVANTAGES OF INDEPENDENTS Independent retailers have various advantages and disadvantages. The following are among the advantages:

- There is flexibility in choosing retail formats and locations and in devising strategy. Because only one location is involved, detailed specifications can be set for the best site and a thorough search undertaken. Uniform location standards are not needed, as they are for chains, and independents do not have to worry about stores being too close together. Independents have great latitude in selecting target markets. Because they often have modest goals, small segments may be selected rather than the mass market. Assortments, prices, hours, and other factors are then set consistent with the segment.

- Investment costs for leases, fixtures, workers, and merchandise can be held down; and there is no duplication of stock or personnel. Responsibilities are clearly delineated within a store.

- Independents frequently act as specialists in a niche of a particular goods/service category. They are then more efficient and can lure shoppers interested in specialized retailers.

- Independents exert strong control over their strategies, and the owner-operator is often on the premises. Decisions are centralized and layers of management personnel are minimized.

- There is a certain image attached to independents, particularly small ones that chains cannot readily capture. This is the image of a personable retailer with a comfortable atmosphere in which to shop.

- Independents can easily sustain consistency in their efforts since only one store is operated.

- Independents have “independence.” They do not have to fret about stockholders, board of directors meetings, and labor unrest. They are often free from unions and seniority rules.

- Owner-operators typically have a strong entrepreneurial drive. They have made a personal investment and there is a lot of ego involvement. Research shows that independent retailers are more likely to “put customers’ interests first.” Their personal interaction with customers, flat organizational structure, and limited resources lead to efficient and effective customer- oriented planning that improves profitability.3

These are some of the disadvantages of independent retailing:

- In bargaining with suppliers, independents may not have much power because they often buy in small quantities. Suppliers may even bypass them. Reordering may be difficult if minimum order requirements are high. Some independents, such as hardware stores, belong to buying groups to increase their clout.

- Independents generally cannot gain economies of scale in buying and maintaining inventory. Due to financial constraints, small assortments are bought several times per year. Transportation, ordering, and handling costs per unit are high.

- Operations are labor intensive, sometimes with little computerization. Ordering, taking inventory, marking items, ringing up sales, and bookkeeping may be done manually. This is less efficient than computerization. In many cases, owner-operators are unwilling or unable to spend time learning how to set up and apply computerized procedures.

- Due to the relatively high costs of TV ads and the broad geographic coverage of magazines and some newspapers (too large for firms with one outlet), independents are limited in their access to certain media. Yet, there are various promotion tools available for creative independents (see Chapter 19).

- A crucial problem for independents is overdependence on the owner. All decisions may be made by that person, and there may be no management continuity when the owner-boss is ill, on vacation, or retires. Financial concerns like how to pay bills, collect accounts receivables, and make payroll or the bank loan can overwhelm an independent retailer. This can also affect employee morale and long-run success.4

- A limited amount of time is allotted to long-run planning because the owner is intimately involved in daily operations of the firm.

2. Chain

A chain retailer operates multiple outlets (store units) under common ownership; it usually engages in some level of centralized (or coordinated) purchasing and decision making. In the United States, there are more than 110,000 retail chains that operate about 1 million establishments.

The relative strength of chain retailing is great, even though the number of firms is small (less than 5 percent of all U.S. retail firms). Chains today operate about 30 percent of retail establishments, and because stores in chains tend to be considerably larger than those run by independents, chains account for roughly three-quarters of total U.S. store sales and employment. Although the majority of chains have 5 or fewer outlets, the several hundred firms with 100 or more outlets account for more than 60 percent of U.S. retail sales. Some big U.S. chains have at least 1,000 outlets each. There are also many large foreign chains, as seen in Figure 4-3.

Chain dominance varies by type of retailer. Chains generate at least 75 percent of total U.S. category sales for department stores, discount department stores, and grocery stores. On the other hand, stationery, beauty salon, furniture, and liquor store chains produce far less than 50 percent of U.S. retail sales in their categories.

COMPETITIVE ADVANTAGES AND DISADVANTAGES OF CHAINS There are numerous competitive advantages for chain retailers:

- Many chains have bargaining power due to their purchase volume. They receive new items when introduced, have orders promptly filled, get sales support, and obtain quantity discounts. Large chains may also gain exclusive rights to certain items and have private-label goods produced under the chains’ brands.

- Chains achieve cost efficiencies when they buy directly from manufacturers and in large volume, ship and store goods, and attend trade shows sponsored by suppliers to learn about new offerings. They can sometimes bypass wholesalers, which results in lower supplier prices.

- Efficiency is gained by sharing warehouse facilities, purchasing standardized store fixtures, and so on; by centralized buying and decision making; and by other practices. Chains typically give headquarters’ executives broad authority for personnel policies and for buying, pricing, and advertising decisions.

- Chains use computers in ordering merchandise, taking inventory, forecasting, ringing up sales, and bookkeeping. This increases efficiency and reduces overall costs.

- Chains, particularly national or regional ones, can take advantage of a variety of media, from TV to magazines to newspapers to online blogs.

- Most chains have defined management philosophies, with detailed strategies and clear employee responsibilities. There is continuity when managerial personnel are absent or retire because there are qualified people to fill in and succession plans in place. See Figure 4-4.

- Many chains expend considerable time on long-run planning and assign specific staff to planning on a permanent basis. Opportunities and threats are carefully monitored.

Chain retailers also have a number of disadvantages:

- After chains are established, flexibility may be limited. New nonoverlapping store sites may be hard to find. Consistent strategies must be maintained throughout all units, including prices, promotions, and product assortments. It may be difficult to adapt to local diverse markets. Investments are higher due to multiple leases and fixtures. There is higher investment in inventory due to the number of store branches that must be stocked.

- Managerial control is complex, especially for chains with geographically dispersed branches. Top management cannot maintain the control over each branch that independents have over their single outlet. Lack of communication and delays in making and enacting decisions are particularly problematic.

- Personnel in large chains often have limited independence because there are several management layers and unionized employees. Some chains empower personnel to give them more authority.

3. Franchising

Franchising involves a contractual arrangement between a franchisor (a manufacturer, wholesaler, or service sponsor) and a retail franchisee, which allows the franchisee to conduct business under an established name and according to a given pattern of business. The franchisee typically pays an initial fee and a monthly percentage of gross sales in exchange for the exclusive rights to sell goods and services in an area. Small businesses benefit by being part of a large, chain-type retail institution.

In product/trademark franchising, a franchisee acquires the identity of a franchisor by agreeing to sell the latter’s products and/or operate under the latter’s name. The franchisee operates rather autonomously. There are some operating rules, but the franchisee sets hours, chooses a location, and determines facilities and displays. Product/trademark franchising represents 60 percent of retail franchising sales. Examples are auto dealers and many gasoline service stations.

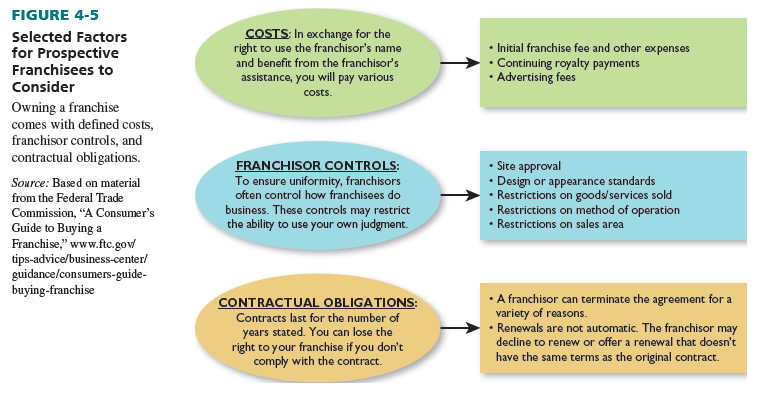

With business format franchising, there is a more interactive relationship between a franchisor and a franchisee. The franchisee receives assistance on site location, quality control, accounting systems, startup practices, management training, and responding to problems besides the right to sell goods and services. Prototype stores, standardized product lines, and cooperative advertising foster a level of coordination previously found only in chains. Business format franchising arrangements are common for restaurants and other food outlets, real-estate, and service retailing. Due to the small size of many franchisees, business formats account for about 80 percent of franchised outlets, although just 40 percent of total sales (including auto dealers). See Figure 4-5.

McDonald’s (www.aboutmcdonalds.com/mcd/franchising.html) is a good example of a business format franchise arrangement. The firm provides franchisee training at Hamburger University, a detailed operating manual, regular visits by service managers, and brush-up training. In return for a 20-year franchising agreement with McDonald’s, a traditional franchisee generally must put up a minimum of $500,000 of nonborrowed personal resources and typically pays ongoing royalty fees totaling at least 12.5 percent of gross sales to McDonald’s.

SIZE AND STRUCTURAL ARRANGEMENTS Although auto and truck dealers provide more than one-half of all U.S. retail franchise sales, few sectors of retailing have been unaffected by franchising’s growth. In the United States, there are more than 3,000 retail franchisors doing business with 350,000+ franchisees. They operate 850,000 franchisee- and franchisor-owned outlets, employ several million people, and generate one-third of total store sales. In addition, hundreds of U.S.-based franchisors have foreign operations, with tens of thousands of outlets.

About 85 percent of U.S. franchising sales and franchised outlets involve franchisee- owned units; the rest involve franchisor-owned outlets. If franchisees operate one outlet, they are independents; if they operate two or more outlets, they are chains. Today, a large number of franchisees operate as chains.

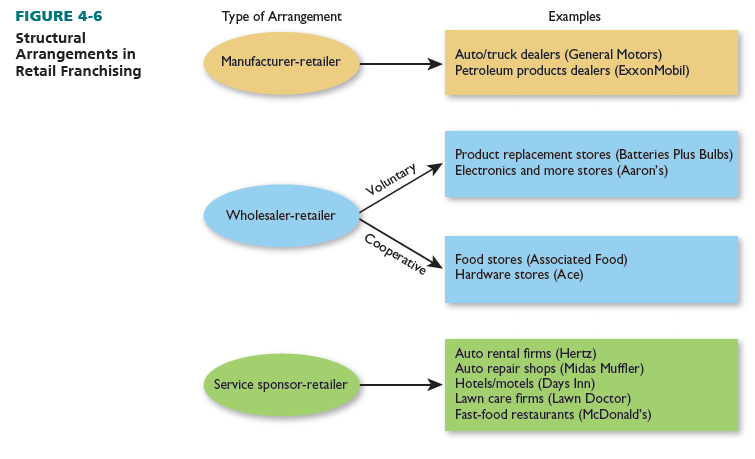

As Figure 4-6 shows, three structural arrangements dominate retail franchising:

- Manufacturer-retailer. A manufacturer gives independent franchisees the right to sell goods and related services through a licensing agreement.

- Wholesaler-retailer.

- Voluntary. A wholesaler sets up a franchise system and grants franchises to individual retailers.

- Cooperative. A group of retailers sets up a franchise system and shares the ownership and operations of a wholesaling organization.

- Service sponsor-retailer. A service firm licenses individual retailers so they can offer specific service packages to consumers.

COMPETITIVE ADVANTAGES AND DISADVANTAGES OF FRANCHISING Franchisees receive several benefits by investing in successful franchise operations:

- They own a retail enterprise with a relatively small capital investment.

- They acquire well-known names and goods/service lines.

- Standard operating procedures and management skills may be taught to them.

- Cooperative marketing efforts (such as regional or national advertising) are facilitated.

- They obtain exclusive selling rights for specified geographical territories.

- Their purchases may be less costly per unit due to the volume of the overall franchise.

- Some potential problems do exist for franchisees:

- Oversaturation could occur if too many franchisees are in one geographic area.

- Due to overzealous selling by some franchisors, franchisees’ income potential, required managerial ability, and investment may be incorrectly stated.

- They may be locked into contracts requiring purchases from franchisors or certain vendors. Cancellation clauses may give franchisors the right to void agreements if provisions are not satisfied.

- In some industries, franchise agreements are of short duration.

- Royalties are often a percentage of gross sales, regardless of franchisee profits.

The preceding factors contribute to constrained decision making, whereby franchisors limit franchisee involvement in the strategic planning process.

The Federal Trade Commission (FTC) has a rule as to disclosure requirements and business opportunities (www.ftc.gov/tips-advice/business-center/guidance/amended-franchise-rule-faqs) that applies to all U.S. franchisors. It is intended to provide adequate information to potential franchisees prior to their investment. Although the FTC does not regularly review disclosure statements, nearly 20 states check them and may require corrections. Several states (including Arkansas, California, Hawaii, Illinois, Indiana, Maryland, Michigan, Minnesota, Mississippi, Nebraska, South Dakota, Virginia, Washington, and Wisconsin) have fair practice laws that do not let franchisors terminate, cancel, or fail to renew franchisees without just cause. The FTC has a franchising Web site (https://goo.gl/ivfnSW), as highlighted in Figure 4-7.

Franchisors accrue lots of benefits by having franchise arrangements:

A national or global presence is developed more quickly and with less franchisor investment.

- Franchisee qualifications for ownership are set and enforced.

- Agreements require franchisees to abide by stringent operating rules set by franchisors.

- Money is obtained when goods are delivered rather than when they are sold.

- Because franchisees are owners and not employees, they have more incentive to work hard.

- Even after franchisees have paid for their outlets, franchisors receive royalties and may sell products to the individual proprietors.

Franchisors also face potential problems:

- Franchisees harm the overall reputation if they do not adhere to company standards.

- A lack of uniformity among outlets adversely affects customer loyalty.

- Intrafranchise competition is not desirable.

- The resale value of individual units is injured if franchisees perform poorly.

- Ineffective franchised units directly injure franchisors’ profitability that results from selling services, materials, or products to the franchisees and from royalty fees.

- Franchisees, in greater numbers, are seeking to limit franchisors’ rules and regulations.

Further information on franchising is in the appendix at the end of this chapter. Also, visit our blog for a lot of posts on this topic (www.bermanevansretail.com).

4. Leased Department

A leased department is a department in a retail store—usually a department, discount, or specialty store—that is rented to an outside party. The leased department proprietor is responsible for all aspects of its business (including fixtures) and normally pays a percentage of sales as rent. The host retailer earns a steady income renting out extra space and the leased department gets market access at a smaller footprint at a lower negotiated cost. The store sets operating restrictions for the leased department to ensure overall consistency and coordination.7

Leased departments (sometimes called “stores within a store” or kiosks with even smaller footprints) are used by store-based retailers to broaden their offerings into product categories that often are on the fringe of the store’s major product lines. They are most common for in-store beauty salons; banks; photographic studios; and shoe, jewelry, cosmetics, watch repair, and shoe repair departments. Leased departments are also popular in shopping center food courts. They account for $20 billion in annual department store sales. More luxury brands, such as Gucci and Dior, are leasing out departments to have greater control over the way their products are sold. Data on overall leased department sales are not available.

The stores-within-a-store concept provides host retailers and their lessees with opportunities to cross-market their brands and reach new demographics. Leased spaces can add excitement to the customers’ shopping experience, add variety to the retailer’s product assortment, and encourage customers to linger longer and make impulse purchases. The success and failure of this strategy for the retailer depends on the choice of the right retail partners, making sure they complement the host retailer and have the potential to attract a new customer base for the host retailer. The strategy must also be supported by an appropriate level of advertising by both the host retailer and retail partners to generate awareness of the locations of the leased department stores. A successful example is Sephora, which has operated leased departments in J.C. Penney stores since 2006. Sephora’s presence has helped energize and reinvent Penney’s image.

Here are other examples: CVS bought the rights to run Target’s pharmacies and health clinics at 1,660 locations for $1.9 billion; it rebranded them as CVS with added digital healthcare tools. This increased CVS’s retail footprint by 20 percent and helped capture pharmacy purchases made in general merchandise stores. Target can offer customers integrated pharmacy services with CVS expertise, and focus on improving performance in its core product areas.8 Finish Line offers an exclusive shoe line in its almost 600-branded shops at Macy’s department stores. As a result, Finish Line has enjoyed strong sales and Macy’s has seen an increase in foot traffic.9

For retailers facing declining sales, leasing out space may be part of a retrenchment strategy, to reduce their footprint while generating stable income. Sears hosts the trendy Forever 21, a women’s fashions business. Walmart Realty says it has almost 400 in-store leases ready for some well-matched retailer that sees a benefit in letting “Walmart’s repeat customers become [their] repeat customers.” Retailers in Europe and Asia have used the concept extensively—nearly all major Chinese retailers are really a conglomeration of ever-changing smaller stores that stand up in competition or are pruned from the landscape.10

COMPETITIVE ADVANTAGES AND DISADVANTAGES OF LEASED DEPARTMENTS From the stores’ perspective, leased departments offer a number of benefits:

The market is enlarged by providing one-stop customer shopping.

- Personnel management, merchandise displays, and reordering are undertaken by lessees.

- Regular store personnel do not have to be involved.

- Leased department operators pay for some expenses, thus reducing store costs.

- A percentage of revenues is received regularly.

There are also some potential pitfalls from the stores’ perspective:

- Leased department operating procedures may conflict with store procedures.

- Lessees may adversely affect stores’ images.

- Customers may blame problems on the stores rather than on the lessees.

For leased department operators, there are these advantages:

- Stores are known, have steady customers, and offer immediate sales for leased departments.

- Some costs are reduced through shared facilities, such as security equipment and display windows.

- Their image is enhanced by their relationships with popular stores.

- The operators have greater control over their own image and selling strategy than if the retailers act as the resellers.

Lessees face these possible problems:

- There may be inflexibility as to the hours they must be open and the operating style.

- The goods/service lines are usually restricted.

- If they are successful, stores may raise rent or not renew leases when they expire.

- In-store locations may not generate the sales expected.

An example of a thriving long-term lease arrangement is one between Luxottica and Macy’s. Luxottica started with Sunglass Hut shops in Macy’s stores in 2009 to offer optical products and services to Macy’s customers. Sunglass Hut shops have grown to 670 Macy’s locations; and in April 2016, Luxottica agreed to establish LensCrafters shops in 500 Macy’s locations.11

5. Vertical Marketing System

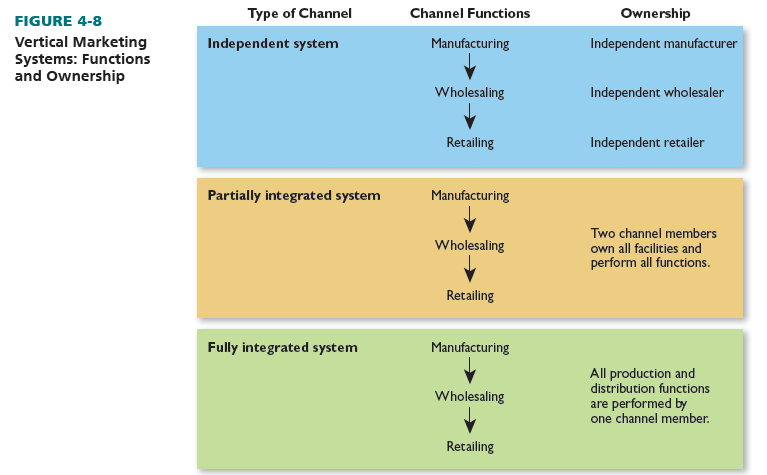

A vertical marketing system consists of all the levels of independently owned businesses along a channel of distribution. Goods and services are normally distributed through one of these systems: independent, partially integrated, and fully integrated. See Figure 4-8.

In an independent vertical marketing system, there are three levels of independently owned firms: manufacturers, wholesalers, and retailers. Such a system is most often used if manufacturers or retailers are small, intensive distribution is sought, customers are widely dispersed, unit sales are high, company resources are low, channel members seek to share costs and risks, and task specialization is desirable. Independent vertical marketing systems are used by many stationery stores, gift shops, hardware stores, food stores, drugstores, and many other firms. They are the leading form of vertical marketing system.

With a partially integrated system, two independently owned businesses along a channel perform all production and distribution functions. It is most common when a manufacturer and a retailer complete transactions and shipping, storing, and other distribution functions in the absence of a wholesaler. This system is most apt if manufacturers and retailers are large, selective or exclusive distribution is sought, unit sales are moderate, company resources are high, greater channel control is desired, and existing wholesalers are too expensive or unavailable. Partially integrated systems are often used by furniture stores, appliance stores, restaurants, computer retailers, and mail-order firms.

Through a fully integrated system, one firm performs all production and distribution functions. The firm has total control over its strategy, direct customer contact, and exclusivity over its offering; it also keeps all profits. This system can be costly and requires a lot of expertise. In the past, vertical marketing was employed mostly by manufacturers, such as Avon and Sherwin- Williams. At Sherwin-Williams, its own 4,100 paint stores account for nearly 60 percent of total company sales.12 Today, more retailers (such as Kroger) use fully integrated systems for at least some products.

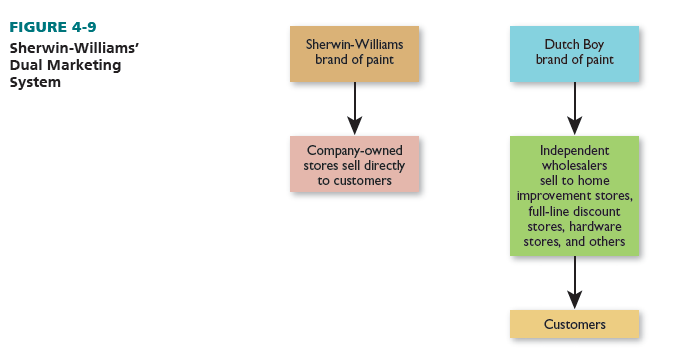

Some firms use dual marketing (a form of multichannel retailing) and engage in more than one type of distribution arrangement. Thus, firms appeal to different consumers, increase sales, share some costs, and retain a lot of strategic control. One example is Sherwin-Williams which sells Sherwin-Williams paints at company stores, but it sells Dutch Boy paints in home-improvement stores, full-line discount stores, hardware stores, and others. See Figure 4-9. As another example, in addition to its traditional standalone outlets, Dunkin’ Donuts and Baskin-Robbins share facilities in numerous locations, so as to attract more customers and increase the revenue per transaction.

Besides partially or fully integrating a vertical marketing system, a firm can exert power in a distribution channel because of its economic, legal, or political strength; superior knowledge and abilities; customer loyalty; or other factors. With channel control, one member of a distribution channel dominates the decisions made in that channel due to the power it possesses. Manufacturers, wholesalers, and retailers each have a combination of tools to improve their positions relative to one another.

Manufacturers exert control by franchising, developing strong brand loyalty, pre-ticketing items (to designate suggested prices), and using exclusive distribution with retailers that agree to certain standards in exchange for sole distribution rights in an area. Wholesalers exert influence when they are large, introduce their own brands, sponsor franchises, and are the most efficient members in the channel for tasks such as processing reorders. Retailers exert clout when they represent a large percentage of a supplier’s sales volume and when they foster their own brands. Private brands let retailers switch vendors with no impact on customer loyalty, as long as the same product features are included.

Strong long-term channel relationships often benefit all parties. They lead to scheduling efficiencies and cost savings. Advertising, financing, billing, and other tasks are greatly simplified.

6. Consumer Cooperative

A consumer cooperative is a retail firm owned by its customer members. A group of consumers invests, elects officers, manages operations, and shares the profits or savings that accrue.13 In the United States, there are several thousand such cooperatives, from small buying clubs to Recreational Equipment Inc. (REI), with $2.5 billion in annual sales. Consumer cooperatives have been most popular in food retailing. Yet, the 500 or so U.S. food cooperatives account for less than 1 percent of total grocery sales.

Consumer cooperatives exist for these basic reasons: Some consumers feel they can operate stores as well as or better than traditional retailers. They think existing retailers inadequately fulfill customer needs for healthful, environmentally safe products. They also assume existing retailers make excessive profits and that they can sell merchandise for lower prices.

Recreational Equipment Inc. sells outdoor recreational equipment to 5.5 million members and other customers. It has about 140 stores, a mail-order business, and a Web site (www.rei.com). Unlike other cooperatives, REI is run by a professional staff that adheres to policies set by the member-elected board. There is a $20 one-time membership fee, which allows customers to shop at REI, vote for directors, and share in profits (based on the amount spent by each member). REI’s goal is to distribute a regular dividend to members.

Cooperatives are only a small part of retailing because they involve consumer initiative and drive, consumers are usually not expert in retailing functions, cost savings and low selling prices are often not as expected, and consumer boredom in running a cooperative frequently occurs.

Source: Barry Berman, Joel R Evans, Patrali Chatterjee (2017), Retail Management: A Strategic Approach, Pearson; 13th edition.

amazing post