This appendix is presented because of franchising’s strong retailing presence and the exciting opportunities in franchising. Over the past two decades, annual U.S. franchising sales have more than tripled! Here, we go beyond the discussion of franchising in Chapter 4 and provide information on managerial issues in franchising and on franchisor-franchisee relationships.

Consider this, for example: In 1999, Tariq and Kamran Farid opened their first Edible Arrangements store in East Haven, Connecticut. The initial franchised store opened during 2001 in Waltham, Massachusetts. Now, due to franchising, Edible Arrangements has over 1,200 stores worldwide, mostly franchised. The firm was recently ranked number 9 on Forbes magazine’s “Top Franchises for the Money” and number 1 in its category in “Entrepreneur Magazine’s Franchise 500” (for nine consecutive years) and also regularly appears in Entrepreneur’s “Top 50 of the “Fastest-Growing Franchises,” and “America’s Top Global Franchises,”1

How about Dunkin’ Donuts? It is the number 1 retailer of hot and iced regular coffee-by-the- cup in the United States and the largest coffee and baked goods chain in the world. Dunkin’ Donuts sells over 1.7 billion cups of coffee per year with 70 varieties of donuts and over a dozen coffee beverages (as well as bagels, breakfast sandwiches, and other baked goods).There are over 8,000 franchised Dunkin’ Donuts in the United States and an additional 3,200 shops in over 32 countries throughout the world. Financial requirements are a minimum net worth of $500,000 and a minimum liquid capital of $250,000.2

U.S. franchisors are situated in over 170 countries, a number that is rising due to these factors: U.S. firms see the foreign market potential. Franchising is accepted as a retailing format in more nations. And trade barriers are fewer due to such pacts as the North American Free Trade Agreement, which makes it easier for firms based in the United States, Canada, and Mexico to operate in each other’s marketplaces.

The following Web sites will give you more information on franchising:

- Federal Trade Commission (https://www.ftc.gov/tips-advice/business-center/guidance/ consumers-guide-buying-franchise)

- International Franchise Association (http://www.franchise.org/)

- Small Business Administration (https://www.sba.gov/starting-business/how-start-business/ business-types/franchise-businesses)

1. Managerial Issues in Franchising

Franchising appeals to franchisees for several reasons. Most franchisors have easy-to-learn, standardized operating methods that they have perfected. Also, new franchisees do not have to learn from their own trial-and-error method. Additionally, franchisors often have facilities where franchisees are trained to operate equipment, manage employees, keep records, and improve customer relations; there are usually follow-up field visits.

A new outlet of a nationally advertised franchise (such as Burger King) can attract a large customer following rather quickly and easily because of the reputation of the firm. And not only does franchising result in good initial sales and profits but it also reduces franchisees’ risk of failure if the franchisees affiliate with strong, supportive franchisors.

Investment and startup costs for a franchised outlet can be as low as a few thousand dollars for a personal service business to as high as several million dollars for a hotel. In return for its expenditures, a franchisee gets exclusive selling rights for an area; a business format franchisee gets training, equipment and fixtures, and support in site selection; as well as supplier negotiations, advertising, and so on. Besides receiving fees and royalties from franchisees, franchisors may sell goods and services to them. This may be required—more often, for legal reasons, such purchases are at the franchisees’ discretion (subject to franchisor specifications). Each year, franchisors sell billions of dollars’ worth of items to franchisees.

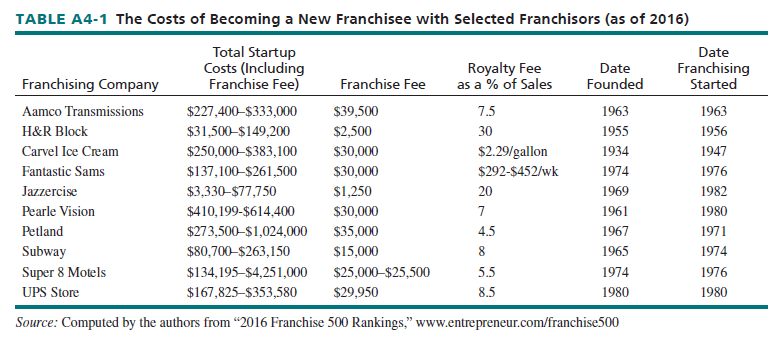

Table A4-1 shows the franchise fees, startup costs, and royalty fees for new franchisees at 10 leading franchisors in various business categories. Financing support—either through in-house financing or third-party financing—is offered by most of the firms cited in Table A4-1. In addition, with its guaranteed loan program, the U.S. Small Business Administration is a good financing option for prospective franchisees, and some banks offer special interest rates for franchisees affiliated with established franchisors.

Franchised outlets can be bought (leased) from franchisors, master franchisees, or existing franchisees. Franchisors sell either new locations or company-owned outlets (some of which may have been taken back from unsuccessful franchisees). At times, they sell rights in entire regions or counties to master franchisees, which deal with individual franchisees. Existing franchisees usually have the right to sell their units if they first offer them to their franchisor, if potential buyers meet all financial and other criteria, and/or if buyers undergo training. Of interest to prospective franchisees is the emphasis a firm places on franchisee-owned outlets versus franchisor-owned ones.

One last point regarding managerial issues in franchising concerns the failure rate of new franchisees. For many years, it was believed that success as a franchisee was a “sure thing”—and much safer than starting a business—due to the franchisor’s well-known name, its experience, and its training programs. However, some recent research has shown franchising to be as risky as opening a new business. Why? Some franchisors have oversaturated the market and not provided promised support, and unscrupulous franchisors have preyed on unsuspecting investors.

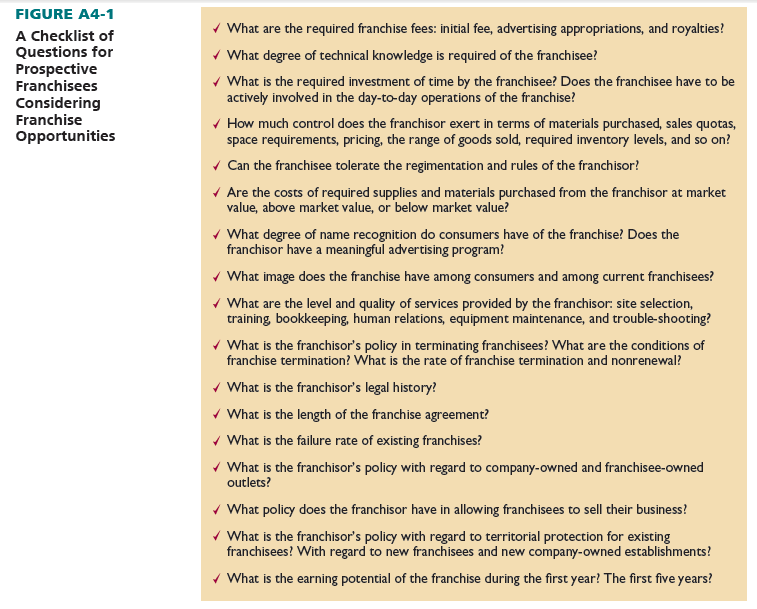

Figure A4-1 has a checklist by which potential franchisees can assess opportunities. In using the checklist, franchisees should also obtain full prospectuses and financial reports from all franchisors under consideration, and talk to existing franchise operators and customers.

2. Franchisor-Franchisee Relationships

Many franchisors and franchisees have good relationships because they share goals for company image, operations, the goods and services offered, cooperative ads, and sales and profit growth.

Nonetheless, for several reasons, tensions do sometimes exist between various franchisors and their franchisees:

- The franchisor-franchisee relationship is not one of employer to employee. Franchisor controls are often viewed as rigid.

- Many agreements are considered too short by franchisees.

- The loss of a franchise often means eviction, and the franchisee gets nothing for “goodwill.”

- Some franchisors believe their franchisees do not reinvest enough in their outlets or care enough about the consistency of operations from one outlet to another.

- Franchisors may not give adequate territorial protection and may open new outlets or allow other franchisees to locate near existing ones.

- Franchisees may refuse to participate in cooperative advertising programs.

- Franchised outlets up for sale must usually be offered first to franchisors, which also have approval of sales to third parties.

- Some franchisees believe franchisor marketing support is low.

- Franchisees may be prohibited from operating competing businesses.

- Restrictions on suppliers may cause franchisees to pay more and have limited choices.

- Franchisees may band together to force changes in policies and exert pressure on franchisors.

- Sales and profit expectations may not be realized.

Tensions can lead to conflicts—even litigation. Potential negative franchisor actions include ending agreements; reducing marketing support; and adding red tape for orders, data requests, and warranty work. Potential negative franchisee actions include ending agreements, adding competitors’ items, not promoting goods and services, and not complying with data requests.

Although franchising has been characterized by franchisors having more power than franchisees, this inequality is being reduced. First, franchisees affiliated with specific franchisors have joined together. For example, the Association of Kentucky Fried Chicken Franchisees and National Coalition of Associations of 7-Eleven Franchisees represent thousands of franchisees. Second, large umbrella groups, such as the American Franchisee Association (www.franchisee .org) and the American Association of Franchisees & Dealers (www.aafd.org), have been formed. Third, many franchisees now operate more than one outlet, so they have greater clout. Fourth, there has been a substantial rise in litigation.

Better communication and better cooperation help resolve problems. Two progressive tactics are the International Franchise Association (www.franchise.org/mission-statementvisioncode-of- ethics), which has an ethics code for its franchisor and franchisee members, founded on the principle that each franchisor-franchisee relationship requires mutual commitment by both parties. The National Franchise Mediation Program seeks to resolve franchisor-franchisee disagreements. All mediation efforts are voluntary, confidential, nonbinding, and informal: “Typically, disputes that are mediated are concluded expeditiously at moderate cost compared to disputes that are arbitrated or litigated. Since its inception in 1993, a success rate of approximately 90 percent has been achieved in mediations in which the franchisee agreed to participate and in which a mediator was needed. Many cases are resolved without intervention of a mediator.”3

The Business Owner’s Toolkit (www.bizfilings.com/toolkit) is an excellent resource for the independent retailer.

Source: Barry Berman, Joel R Evans, Patrali Chatterjee (2017), Retail Management: A Strategic Approach, Pearson; 13th edition.

I was recommended this website by my cousin. I am not sure whether this post is written by him as no one else know such detailed about my trouble. You’re amazing! Thanks!