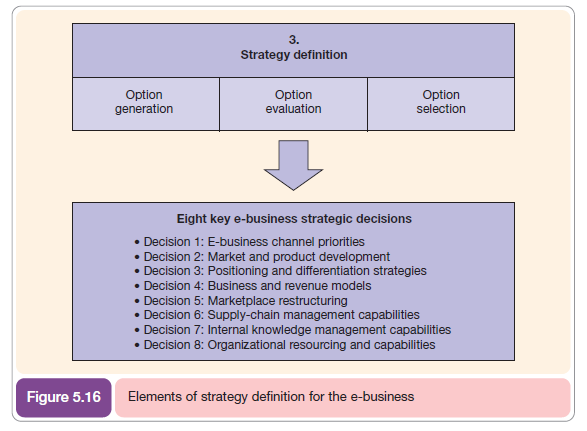

In this section the key strategic decisions faced by a management team developing e-business strategy are reviewed. For each of the areas of strategy definition that we cover, managers will want to generate different options, review them and select them as shown in Figure 5.16. We start by considering the sell-side-related aspects of e-business and then review the buy-side- related aspects.

Selection of e-business strategy options

When reviewing e-business strategy options, there will be a range of possible strategies and e-business service alternatives to be evaluated. Limited resources will dictate that only some applications are practical. For example, typical alternative e-business strategy options for an organization which has a brochureware site might be to implement:

- transactional e-commerce facility;

- online catalogue facility;

- e-CRM system – lead generation system;

- e-CRM system – customer service management;

- e-CRM system – personalization of content for users;

- e-procurement system for office supplies;

- partner relationship management extranet for distributors and agents;

- social network or customer forum.

Portfolio analysis (introduced in the section on resource and process analysis) can be used to select the most suitable e-business projects from candidates. For example, Daniel et al. (2001) suggest that potential e-commerce opportunities should be assessed for the value of the opportunity to the company against its ability to deliver. Similarly, McDonald and Wilson (2002) suggest evaluations should be based on a matrix of attractiveness to customer against attractiveness to company, which will give a similar result to the risk-reward matrix.

Tjan (2001) also suggested a matrix approach of viability (return on investment) against fit (with the organization’s capabilities) for Internet applications. He presents the following metrics for assessing viability of each application. For ‘fit’ these are:

- Alignment with core capabilities

- Alignment with other company initiatives

- Fit with organizational structure

- Fit with company’s culture and value

- Ease of technical implementation.

For ‘viability’ the metrics are:

- Market value potential (return on investment)

- Time to positive cash flow

- Personnel requirement

- Funding requirement.

Econsultancy (2008a) also recommends a form of portfolio analysis (Figure 5.17) as the basis for benchmarking current e-commerce capabilities and identifying strategic priorities. The six criteria used for organizational value and fit (together with a score or rating for their relative effectiveness) are:

- Business value generated (0-50). These should be based on incremental financial benefits of the project. These can be based on conversion models showing estimated changes in number of visitors attracted (new and repeat customers), conversion rates and results produced. Consideration of lifetime value should occur here.

- Customer value generated (0-20). This is a ‘softer’ measure which assesses the impact of the delivered project on customer sentiment, for example, would they be more or less likely to recommend a site, would it increase their likelihood to visit or buy again?

- Alignment with business strategy (0-10). Projects which directly support current business goals should be given additional weighting.

- Alignment with digital strategy (0-10). Likewise for digital strategy.

- Alignment with brand values (0-10). And for brand values.

The cost elements for potential e-business projects are based on requirements for internal people resource (cost/time), agency resource (cost/time), set-up costs and technical feasibility, ongoing costs and business and implementation risks.

Decision 1: E-business channel priorities

The e-business strategy must be directed according to the priority of different strategic objectives such as those in Table 5.6. If the priorities are for the sell-side downstream channel, as are objectives 1 to 3 in Table 5.6, then the strategy must be to direct resources at these objectives. For a B2B company that is well known in its marketplace worldwide and cannot offer products to new markets, an initial investment on buy-side channel upstream channel e-commerce and value chain management maybe more appropriate.

E-business channel strategy priorities can be summarized in the words of Gulati and Garino (2000) ‘Getting the right mix of bricks and clicks’. This expression usually refers to sell-side e-commerce. The general options for the mix of‘bricks and clicks’ are shown in Figure 5.18. This summarizes an organization’s commitment to e-commerce and its implication for traditional channels. The other strategy elements that follow define the strategies for how the target online revenue contribution will be achieved.

A similar figure was produced by de Kare-Silver (2000) who suggests that strategic e-commerce alternatives for companies should be selected according to the percentage of the target market who can be persuaded to migrate to use the e-channel and the benefits to the company of encouraging migration in terms of anticipated sales volume and costs for initial customer acquisition and retention.

Internet-only businesses, particularly start-ups, are sometimes referred to as ‘Internet pure- plays’. Although the ‘switch-fully’ alternative is impractical for many businesses, companies are moving along the curve in this direction. In the UK, the Automobile Association and British Airways have closed the majority of their retail outlets since orders are predominately placed via the Internet or by phone. This makes sense for both of these companies, since no physical products are supplied at point of sale. But both of these companies still make extensive use of the phone channel since its interactivity is needed for many situations. Essentially they have followed a ‘bricks and clicks’ approach; indeed most businesses require some human element of service.

The transition to a service that is clicks-only is unlikely for the majority of companies. Where a retailer is selling a product such as a mobile phone or electronic equipment many consumers naturally want to compare the physical attributes of products or gain advice from the sales person. Companies selling mobile phones and related tariffs such as the Carphone Warehouse, Phones4U and the network providers such as O , Orange, T-Mobile and Vodafone still have a strong high-street presence and the majority of their sales are in-store. Even dot-coms such as lastminute.com have set up a call centre and experimented with a physical presence in airports or train stations since this helps them to reach a key audience and has benefits in promoting the brand. Another example of the importance of a physical presence related by Tse (2007) is this quote from the CEO of Charles Tyrwhitt, a London- based shirtmaker that makes heavy use of the on-line channel:

The picture of its Jermyn Street flagship store on our website ‘is worth as much as having the store (in the shoppers’ native countries). Jermyn Street meant something to the customers, especially those in the US.

Right-channelling

Prioritization of different communications channels to achieve different e-business objectives is an important aspect of e-business strategy. It is necessary to identify which strategies will be pursued, set objectives for them and then define approaches to encourage customers to adopt the appropriate channel. This approach is commonplace and is often referred to as ‘right-channelling’. Right-channelling involves devising a contact strategy and tactics which integrate different channels, supported by technology to reach:

– The Right Person

– At the Right Time

– Using the Right Communications Channel

– With a Relevant Offer, Product or Message

Some examples of right-channelling are given in Table 5.9.

Decision 2: Market and product development strategies

Deciding on which markets to target through digital channels to generate value is a key strategic consideration for e-commerce strategy in the same way as it is key to marketing strategy. Managers of e-business strategy have to decide whether to use new technologies to change the scope of their business to address new markets and new products. As for Decision 1, the decision is a balance between fear of the do-nothing option and fear of poor return on investment for strategies that fail. The model of Ansoff (1957) is still useful as a means for marketing managers to discuss market and product development using electronic technologies. This decision is considered from an e-marketing perspective in Chapter 8. The market and product development matrix (Figure 5.19) can help identify strategies to grow sales volume through varying what is sold (the product dimension on the horizontal axis of Figure 5.19) and who it is sold to (the market dimension on the y-axis). Specific objectives need to be set for sales generated via these strategies, so this decision relates closely to that of objective setting. Let’s now review these strategies in more detail.

- Market penetration. This strategy involves using digital channels to sell more existing products into existing markets. The Internet has great potential for achieving sales growth or maintaining sales by the market penetration strategy. As a starting point, many companies will use the Internet to help sell existing products into existing markets, although they may miss opportunities indicated by the strategies in other parts of the matrix. Figure 5.19 indicates some of the main ways in which the Internet can be used for market penetration:

- Market share growth – companies can compete more effectively online if they have web sites that are efficient at converting visitors to sale and mastery of the online marketing communications techniques reviewed in Chapter 9 such as search engine marketing, affiliate marketing and online advertising.

- Customer loyalty improvement – companies can increase their value to customers and so increase loyalty by migrating existing customers online (see Mini Case Study 5.1 on BA earlier in the chapter) by adding value to existing products, services and brand by developing their online value proposition (see Decision 6).

- Customer value improvement – the value delivered by customers to the company can be increased by increasing customer profitability by decreasing cost to serve (and so price to customers) and at the same time increasing purchase or usage frequency and quantity. These combined effects should drive up sales.

- Market development. Here online channels are used to sell into new markets, taking advantage of the low cost of advertising internationally without the necessity for a supporting sales infrastructure in the customer’s country. The Internet has helped low-cost airlines such as easyJet and Ryanair to enter new markets served by their routes cost-effectively. This is a relatively conservative use of the Internet, but is a great opportunity for SMEs to increase exports at a low cost, but it does require overcoming the barriers to exporting.

Existing products can also be sold to new market segments or different types of customers. This may happen simply as a by-product of having a web site. For example, RS components (www.rswww.com), a supplier of a range of MRO (maintenance, repair and operations) items, found that 10% of the web-based sales were to individual consumers rather than traditional business customers. The UK retailer Argos found the opposite was true with 10% of web-site sales from businesses, when their traditional market was consumer-based. EasyJet also has a section of its web site to serve business customers. The Internet may offer further opportunities for selling to market sub-segments that have not been previously targeted. For example, a product sold to large businesses may also appeal to SMEs they have previously been unable to reach because of the cost of sales via a specialist sales force. Alternatively, a product targeted at young people could also appeal to some members of an older audience and vice versa. Many companies have found that the audience and customers of their web site are quite different from their traditional audience, so this analysis should inform strategy.

- Product development. The web can be used to add value to or extend existing products for many companies. For example, a car manufacture can potentially provide car performance and service information via a web site. But truly new products or services that can be delivered by the Internet only apply for some types of products. These are typically digital media or information products, for example online trade magazine Construction Weekly has diversified to a B2B portal CN Plus (cnplus.co.uk) which has new revenue streams. Similarly, music and book publishing companies have found new ways to deliver products through the new development and usage model such as subscription and pay per use as explained in Chapter 8 in the section on the Product element of the marketing mix. Retailers can extend their product range and provide new bundling options online also.

- Diversification. In this sector, new products are developed which are sold into new markets. The Internet alone cannot facilitate these high-risk business strategies, but it can facilitate them at lower costs than have previously been possible. The options include:

- Diversification into related businesses (for example, a low-cost airline can use the web site and customer e-mails to promote travel-related services such as hotel booking, car rental or travel insurance at relatively low costs).

- Diversification into unrelated businesses – again the web site can be used to promote less- related products to customers – this is the approach used by the Virgin brand, although it is relatively rare.

- Upstream integration – with suppliers – achieved through data exchange between a manufacturer or retailer with its suppliers to enable a company to take more control of the supply chain.

- Downstream integration – with intermediaries – again achieved through data exchange with distributors such as online intermediaries.

The danger of diversification into new product areas is illustrated by the fortunes of Amazon, which was infamous for limited profitability despite multi-billion-dollar sales. Phillips (2000) reported that for books and records, Amazon sustained profitability through 2000, but it is following a strategy of product diversification into toys, tools, electronics and kitchenware. This strategy gives a problem through the cost of promotion and logistics to deliver the new product offerings. Amazon is balancing this against its vision of becoming a ‘one-stop shop’ for online shoppers.

A closely related issue is the review of how a company should change its target marketing strategy. This starts with segmentation, or identification of groups of customers sharing similar characteristics. Targeting then involves selectively communicating with different segments. This topic is explored further in Chapter 8. Some examples of customer segments that are commonly targeted online include:

-

- the most profitable customers – using the Internet to provide tailored offers to the top 20 per cent of customers by profit may result in more repeat business and cross-sales;

- larger companies (B2B) – an extranet could be produced to service these customers, and increase their loyalty;

- smaller companies (B2B) – large companies are traditionally serviced through sales representatives and account managers, but smaller companies may not warrant the expense of account managers. However, the Internet can be used to reach smaller companies more cost-effectively. The number of smaller companies that can be reached in this way maybe significant, so although individual revenue of each one is relatively small, the collective revenue achieved through Internet servicing can be large;

- particular members of the buying unit (B2B) – the site should provide detailed information for different interests which supports the buying decision, for example technical documentation for users of products, information on savings from e-procurement for IS or purchasing managers and information to establish the credibility of the company for decision makers;

- customers who are difficult to reach using other media – an insurance company looking to target younger drivers could use the web as a vehicle for this;

- customers who are brand-loyal – services to appeal to brand loyalists can be provided to support them in their role as advocates of a brand as suggested by Aaker and Joachimsthaler (2000);

- customers who are not brand-loyal – conversely, incentives, promotion and a good level of service quality could be provided by the web site to try and retain such customers.

Decision 3: Positioning and differentiation strategies

Once segments to target have been identified, organizations need to define how to best position their online services relative to competitors according to four main variables: product quality, service quality, price and fulfilment time. As mentioned earlier, Deise et al. (2000) suggest it is useful to review these through an equation of how they combine to influence customer perceptions of value or brand:

Strategies should review the extent to which increases in product and service quality can be matched by decreases in price and time. We will now look at some other opinions of positioning strategies for e-businesses. As you read through, refer back to the customer value equation to note similarities and differences.

Chaston (2000) argues that there are four options for strategic focus to position a company in the online marketplace. He says that these should build on existing strengths, but can use the online facilities to enhance the positioning as follows:

- Product performance excellence. Enhance by providing online product customization.

- Price performance excellence. Use the facilities of the Internet to offer favourable pricing to loyal customers or to reduce prices where demand is low (for example, British Midland Airlines uses auctions to sell underused capacity on flights).

- Transactional excellence. A site such as software and hardware e-tailer Dabs.com (dabs.com) offers transactional excellence through combining pricing information with dynamic availability information on products listing number in stock, number on order and when expected.

- Relationship excellence. Personalization features to enable customers to review sales order history and place repeat orders, for example RS Components (rswww.com).

These positioning options have much in common with Porter’s competitive strategies of cost leadership, product differentiation and innovation (Porter, 1980). Porter has been criticized since many commentators believe that to remain competitive it is necessary to combine excellence in all of these areas. It can be suggested that the same is true for sell-side e-commerce. These are not mutually exclusive strategic options, rather they are prerequisites for success. Customers will probably not judge on a single criterion, but on multiple criteria. This is the view of Kim et al. (2004) who concluded that for online businesses, ‘integrated strategies that combine elements of cost leadership and differentiation will outperform cost leadership or differentiation strategies’.

The type of criteria on which customers judge performance can be used to benchmark the proposition. Table 5.10 summarizes criteria typically used for benchmarking. It can be seen that the criteria are consistent with the strategic postioning options of Chaston (2000). Significantly, the retailers with the best overall score at the time of writing, such as Tesco (grocery retail), smile (online banking) and Amazon (books), are also perceived as the market leaders and are strong in each of the scorecard categories. These ratings have resulted from strategies that enable the investment and restructuring to deliver customer performance.

Plant (2000) also identifies four different positional e-strategic directions which he refers to as technology leadership, service leadership, market leadership and brand leadership. The author acknowledges that these are not exclusive. It is interesting that this author does not see price differentiation as important, rather he sees brand and service as important to success online.

In Chapter 8 we look further at how segmentation, positioning and creating differential advantage should be integral to Internet marketing strategy. We also see how the differential advantage and positioning of an e-commerce service can be clarified and communicated by developing an online value proposition (OVP).

To conclude this section on e-business strategies, complete Activity 5.3 for a different perspective on e-business strategies.

Decision 4: Business, service and revenue models

A further aspect of Internet strategy formulation closely related to product development options is the review of opportunities from new business and revenue models (first introduced in Chapter 2). As well as new business and revenue models, constantly reviewing innovation in services to improve the quality of experience offered is important for e-businesses. We also discuss this later in the context of positioning and differentiation. For example, holiday company Thomson (www.thomson.co.uk) innovates to improve the quality of the purchase experience. Innovations have included: travel guides to destinations, video tours of destinations and hotels, ‘build your own’ holidays and the use of e-mail alerts and RSS (Really Simple Syndication, Chapter 3) feeds with holiday offers. Such innovations can help differentiate from competitors and increase loyalty to a brand online.

Evaluating new models and approaches is important since if companies do not review opportunities to innovate then competitors and new entrants certainly will. Andy Grove of Intel famously said: ‘ Only the paranoid will survivealluding to the need to review new revenue opportunities and competitor innovations. A willingness to test and experiment with new business models is also required. Dell is another example of a tech company that regularly reviews and modifies its business model, as shown in Mini Case Study 5.3. Companies at the bleeding edge of technology such as Google and Yahoo! constantly innovate through acquiring other companies. For example, Google purchased linguistic analysis company Applied Semantics in 2003 to improve its search results algorithm; it developed social networking site Orkut (www.orkut.com) in 2004 (based on a concept developed during the staff’s research time) and Google Earth (via Keyhole Inc). Yahoo! has purchased eGroups, later to become Yahoo! Groups and more recently photo-sharing and tagging service Flickr (www.flickr.com) and shared bookmark tagging service (www.del.cio.us). Microsoft will also acquire companies where appropriate, but in the areas mentioned above has tended to pursue a ‘fast-follower’ strategy based on internally developed technology. For example, many of these services are available through MSN Spaces (http://spaces.msn.com), a rival service to social network site MySpace (www.myspace.com) which was purchased by News Corporation in 2005.

These companies also invest in internal research and development (witness Google Labs (http://labs.google.com), Microsoft Research (http://research.microsoft.com) and Yahoo! Research (http://research.yahoo.com)) and continuously develop and trial new services.

The case study on Tesco.com in Chapter 6 also highlights how innovation in the Tesco business model has been facilitated through online channels

To sound a note of caution, flexibility in the business model should not be to the company’s detriment through losing focus on the core business. A 2000 survey of CEOs of leading UK Internet companies such as Autonomy, Freeserve, NetBenefit and QXL (Durlacher, 2000) indicates that although flexibility is useful this may not apply to business models. The report states:

A widely held belief in the new economy in the past, has been that change and flexibility is good, but these interviews suggest that it is actually those companies who have stuck to a single business model that have been to date more successful. CEOs were not moving far from their starting vision, but that it was in the marketing, scope and partnerships where new economy companies had to be flexible.

So with all strategy options, managers should also consider the ‘do-nothing option’. Here a company will not risk a new business model, but will adopt a ‘wait-and-see’ or ‘fast-follower’ approach to see how competitors perform and respond rapidly if the new business model proves sustainable.

Finally, we can note that companies can make less radical changes to their revenue models through the Internet which are less far-reaching, but may nevertheless be worthwhile. For example:

- Transactional e-commerce sites (for example Tesco.com and lastminute.com) can sell advertising space or run co-branded promotions on site or through their e-mail newsletters or lists to sell access to their audience to third parties.

- Retailers or media owners can sell-on white-labelled services through their online presence such as ISP, e-mail services or photo-sharing services.

- Companies can gain commission through selling products which are complementary (but not competitive to their own). For example, a publisher can sell its books through an affiliate arrangement with an e-retailer.

Decision 5: Marketplace restructuring

We saw in Chapter 2 that electronic communications offer opportunities for new market structures to be created through disintermediation, reintermediation and countermediation within a marketplace. The options for these and countermediation should be reviewed.

In Mini Case Study 5.4 we review the example of 3M (www.3m.com), manufacturer of tens of thousands of products such as Post-it notes and reflective Scotchlite film. These options can be reviewed from both a buy-side and a sell-side perspective.

Decision 6: Supply-chain management capabilities

Supply chain management and e-procurement are discussed further in Chapters 6 and 7. The main e-business strategy decisions that need to be reviewed are:

- How should we integrate more closely with our suppliers, for example through creating an extranet to reduce costs and decrease time to market?

- Which types of materials and interactions with suppliers should we support through e-procurement?

- Can we participate in online marketplaces to reduce costs?

Decision 7: Internal knowledge management capabilities

In addition to the decisions about sell-side and buy-side e-commerce mentioned above, organizations should also review their internal e-business capabilities and in particular how knowledge is shared and processes are developed. Questions which can be answered in this category are:

- How can our intranet be extended to support different business processes such as new product development, customer and supply chain management?

- How can we disseminate and promote sharing of knowledge between employees to improve our competitiveness?

We reviewed intranet management issues in Chapter 3 and knowledge management issues in more detail in Chapter 10 in the ‘Focus on’ section.

Decision 8: Organizational resourcing and capabilities

Once the e-business strategy decisions we have described have been reviewed and selected, decisions are then needed on how the organization needs to change in order to achieve the priorities set for e-business.

Gulati and Garino (2000) identify a continuum of approaches from integration to separation. The choices are:

- In-house division (integration). For example, the RS Components Internet Trading Channel (www. rswww. com).

- Joint venture (mixed). The company creates an online presence in association with another player.

- Strategic partnership (mixed). This may also be achieved through purchase of existing dotcoms, for example, in the UK Great Universal Stores acquired e-tailer Jungle.com for its strength in selling technology products and strong brand, while John Lewis purchased Buy.com’s UK operations.

- Spin-off (separation). For example, the bank Egg is a spin-off from the Prudential financial services company.

Gulati and Garino (2000) give the advantages of the integration approach as being able to use existing brands, being able to share information and achieving economies of scale (e.g. purchasing and distribution efficiencies). They say the spin-off approach gives better focus, more flexibility for innovation and the possibility of funding through flotation. For example, financial services company Egg was able to create a brand distinct from Prudential and has developed new revenue models such as retail sales commission. Gulati and Garino say that separation is preferable in situations where:

- a different customer segment or product mix will be offered online

- differential pricing is required between online and offline

- there is a major channel conflict

- the Internet threatens the current business model

- additional funding or specialist staff need to be attracted.

The other aspects of organizational capability that should be reviewed and changed to improve their ability to deliver e-business strategies are shown in Table 5.11. These include:

- Strategy process and performance improvement. The process for selecting, implementing and reviewing e-business initiatives;

- Structure. Location of e-commerce and the technological capabilities through the software, hardware infrastructure used and staff skills;

- Senior management buy-in. E-business strategies are transformational, so require senior management sponsorship;

- Marketing integration. We have stressed the importance of integrated customer and partner communications through right-channelling. Staff members responsible for technology and marketing need to work together more closely to achieve this;

- Online marketing focus. Strategic initiatives will focus on the three core activities of customer acquisition (attracting site visitors), conversion (generating leads and sales) and retention (encouraging continued use of digital channels).

Source: Dave Chaffey (2010), E-Business and E-Commerce Management: Strategy, Implementation and Practice, Prentice Hall (4th Edition).

We are a gaggle of volunteers and opening a new scheme in our community. Your website offered us with helpful information to paintings on. You’ve done a formidable task and our whole neighborhood might be grateful to you.