When personal taxes are introduced, the firm’s objective is no longer to minimize the corporate tax bill; the firm should try to minimize the present value of all taxes paid on corporate income. “All taxes” include personal taxes paid by bondholders and stockholders.

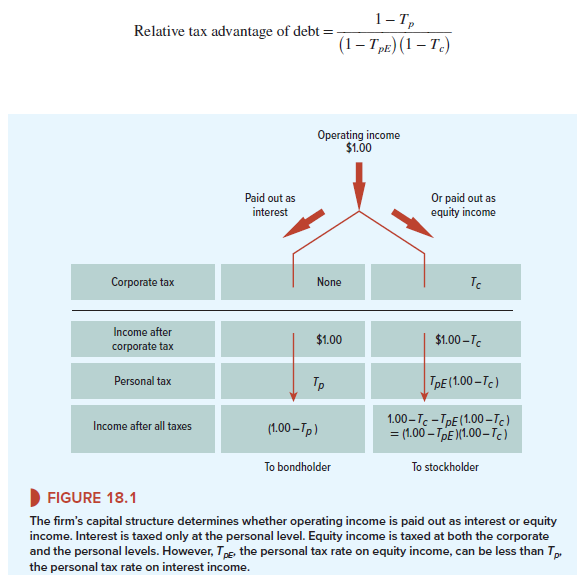

Figure 18.1 illustrates how corporate and personal taxes are affected by leverage. Depending on the firm’s capital structure, a dollar of operating income will accrue to investors either as debt interest or equity income (dividends or capital gains). That is, the dollar can go down either branch of Figure 18.1.

Notice that Figure 18.1 distinguishes between Tp, the personal tax rate on interest, and TpE, the effective personal tax rate on equity income. This rate can be well below Tp, depending on the mix of dividends and capital gains realized by shareholders. The top marginal rate on dividends and capital gains in 2018 is 20% while the top rate on interest income is 37%. Also capital gains taxes can be deferred until shares are sold, so the top effective capital gains rate is usually less than 20%.

The firm’s objective should be to arrange its capital structure to maximize after-tax income. You can see from Figure 18.1 that corporate borrowing is better if (1 – TP) is more than (1 – TpE) x (1 – Tc); otherwise it is worse. The relative tax advantage of debt over equity is

The firm’s capital structure determines whether operating income is paid out as interest or equity income. Interest is taxed only at the personal level. Equity income is taxed at both the corporate and the personal levels. However, TpE, the personal tax rate on equity income, can be less than Tp, the personal tax rate on interest income.

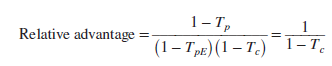

This suggests two special cases. First, suppose that debt and equity income were taxed at the same effective personal rate. With TpE = Tp, the relative advantage depends only on the corporate rate:

In this case, we can forget about personal taxes. The tax advantage of corporate borrowing is exactly as MM calculated it.[1] They do not have to assume away personal taxes. Their theory of debt and taxes requires only that debt and equity income be taxed at the same rate.

The second special case occurs when corporate and personal taxes cancel to make debt policy irrelevant. This requires

![]()

This case can happen only if Tc, the corporate rate, is less than the personal rate Tp and if TpE, the effective rate on equity income, is small. Merton Miller explored this situation at a time when U.S. tax rates on interest and dividends were much higher than now, but we won’t go into the details of his analysis here.[2]

In any event, we seem to have a simple, practical decision rule. Arrange the firm’s capital structure to shunt operating income down that branch of Figure 18.1 where the tax is least. Unfortunately that is not as simple as it sounds. What’s TpE, for example? The shareholder roster of any large corporation is likely to include tax-exempt investors (such as pension funds or university endowments) as well as millionaires and maybe a billionaire or two. All possible tax brackets will be mixed together. And it’s the same with Tp, the personal tax rate on interest. The large corporation’s “typical” bondholder might be a tax-exempt pension fund, but many taxpaying investors also hold corporate debt.

Some investors may be much happier to buy your debt than others. For example, you should have no problems inducing pension funds to lend; they don’t have to worry about personal tax. But taxpaying investors may be more reluctant to hold debt and will be prepared to do so only if they are compensated by a high rate of interest. Investors paying tax on interest at the top rate of 37% may be particularly reluctant to hold debt. They will prefer to hold common stock or tax-exempt bonds issued by states and municipalities.

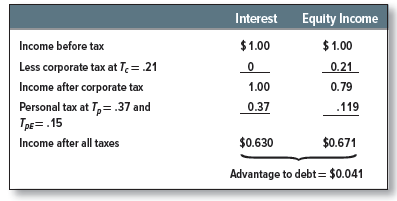

To determine the net tax advantage of debt, companies would need to know the tax rates faced by the marginal investor—that is, an investor who is equally happy to hold debt or equity. This makes it hard to put a precise figure on the tax benefit, but we can nevertheless provide a back-of-the-envelope calculation. On average, over the past 10 years, large U.S. companies have paid out about half of their earnings. Suppose the marginal investor is in the top tax bracket, paying 37% on interest and 20% on dividends and capital gains.

Let’s assume that deferred realization of capital gains cuts the effective capital gains rate in half, to 20/2 = 10%. Therefore, if the investor invests in the stock of a company with a 50% payout, the tax on each $1.00 of equity income is TpE = (.5 X 20) + (.5 X 10) = 15%.

Now we can calculate the effect of shunting a dollar of income down each of the two branches in Figure 18.1:

The advantage to debt financing appears to be about four cents on the dollar.

We should emphasize that our back-of-the-envelope calculation is just that. But it’s interesting to see how debt’s tax advantage shrinks when we account for the relatively low personal tax rate on equity income.

Most financial managers believe that there is a moderate tax advantage to corporate borrowing, at least for companies that are reasonably sure they can use the corporate tax shields. For companies that cannot benefit from corporate tax shields, there is probably a moderate tax disadvantage.

When we recognize personal taxes, the tax advantage to debt diminishes, but it does not disappear. It still appears that financial managers have passed by some easy tax savings. Perhaps they saw some offsetting disadvantage to increased borrowing. We now explore this second escape route.

It¦s actually a great and useful piece of info. I am glad that you shared this useful information with us. Please keep us up to date like this. Thank you for sharing.