Buying a company is a much more complicated affair than buying a piece of machinery. Thus we should look at some of the problems encountered in arranging mergers. In practice, these arrangements are often extremely complex, and specialists must be consulted. We are not trying to replace those specialists; we simply want to alert you to the kinds of legal, tax, and accounting issues that they deal with.

1. Mergers, Antitrust Law, and Popular Opposition

Mergers can get bogged down in the federal antitrust laws. The most important statute here is the Clayton Act of 1914, which forbids an acquisition whenever “in any line of commerce or in any section of the country” the effect “may be substantially to lessen competition, or to tend to create a monopoly.”

Antitrust law can be enforced by the federal government in either of two ways: by a civil suit brought by the Justice Department or by a proceeding initiated by the Federal Trade Commission (FTC).[1] The Hart-Scott-Rodino Antitrust Act of 1976 requires that these agencies be informed of all acquisitions of stock greater than about $75 million. Thus, almost all large mergers are reviewed at an early stage.[2] Both the Justice Department and the FTC then have the right to seek injunctions delaying a merger. An injunction is often enough to scupper the companies’ plans. For example, when Halliburton proposed a $28 billion acquisition of Baker Hughes in 2014, the Justice Department filed a lawsuit to block the merger. The companies tried to deal with the Department’s objections by selling off various business lines to other players. But by 2016 it had become obvious that they could not assuage concerns that the merger would create too much market power, and the companies scrapped their merger plan.

Companies that do business outside the United States also have to worry about foreign antitrust laws. For example, GE’s $46 billion takeover bid for Honeywell was blocked by the European Commission, which argued that the combined company would have too much power in the aircraft industry.

Sometimes trustbusters will object to a merger, but then relent if the companies agree to divest certain assets and operations. For example, when Dow Chemical and DuPont announced plans to merge, the Justice Department required the companies to sell parts of their crop-protection business and two petrochemical plants.

Mergers may also be stymied by political pressures and popular resentment even when no formal antitrust issues arise. In recent years national governments in Europe have become involved in almost all high-profile cross-border mergers and are likely to intervene actively in any hostile bid. For example, the news in 2005 that PepsiCo might bid for Danone aroused considerable hostility in France. The prime minister added his support to opponents of the merger and announced that the French government was drawing up a list of strategic industries that should be protected from foreign ownership. It was unclear whether yogurt production would be one of these strategic industries.

Economic nationalism is not confined to Europe. In 2006, Congress voiced its opposition to the takeover of Britain’s P&O by the Dubai company DP World. The acquisition went ahead only after P&O’s ports in the United States were excluded from the deal. In 2018, the United States blocked Singapore-based Broadcom’s takeover bid for the U.S. chipmaker Qualcom. The U.S. government cited “national security concerns” about giving a foreign entity access to U.S. technology.

2. The Form of Acquisition

Suppose you are confident that the purchase of company B will not be challenged on antitrust grounds. Next you will want to consider the form of the acquisition.

One possibility is literally to merge the two companies, in which case one company automatically assumes all the assets and all the liabilities of the other. Such a merger must have the approval of at least 50% of the stockholders of each firm.16

An alternative is simply to buy the seller’s stock in exchange for cash, shares, or other securities. In this case the buyer can deal individually with the shareholders of the selling company. The seller’s managers may not be involved at all. Their approval and cooperation are generally sought, but if they resist, the buyer will attempt to acquire an effective majority of the outstanding shares. If successful, the buyer has control and can complete the merger and, if necessary, toss out the incumbent management.

The third approach is to buy some or all of the seller’s assets. In this case, ownership of the assets needs to be transferred, and payment is made to the selling firm rather than directly to its stockholders.

3. Merger Accounting

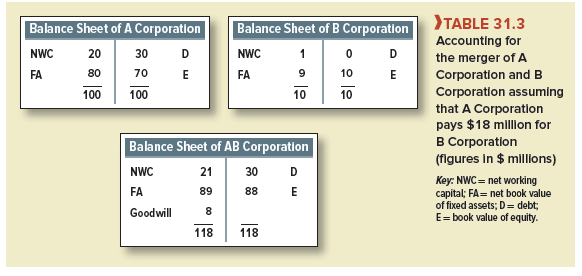

When one company buys another, its management worries about how the purchase will show up in its financial statements. Before 2001, the company had a choice of accounting method, but in that year, the Financial Accounting Standards Board (FASB) introduced new rules that required the buyer to use the purchase method of merger accounting. This is illustrated in Table 31.3, which shows what happens when A Corporation buys B Corporation, leading to the new AB Corporation. The two firms’ initial balance sheets are shown at the top of the table. Below this we show what happens to the balance sheet when the two firms merge. We assume that B Corporation has been purchased for $18 million, 180% of book value.

Why did A Corporation pay an $8 million premium over B’s book value? There are two possible reasons. First, the true values of B’s tangible assets—its working capital, plant, and equipment—may be greater than $10 million. We will assume that this is not the reason; that is, we assume that the assets listed on its balance sheet are valued there correctly. Second, A Corporation may be paying for an intangible asset that is not listed on B Corporation’s balance sheet. For example, the intangible asset may be a promising product or technology. Or it may be no more than B Corporation’s share of the expected economic gains from the merger.

A Corporation is buying an asset worth $18 million. The problem is to show that asset on the left-hand side of AB Corporation’s balance sheet. B Corporation’s tangible assets are worth only $10 million. This leaves $8 million. Under the purchase method, the accountant takes care of this by creating a new asset category called goodwill and assigning $8 million to it.[4] As long as the goodwill continues to be worth at least $8 million, it stays on the balance sheet and the company’s earnings are unaffected.[5] However, the company is obliged each year to estimate the fair value of the goodwill. If the estimated value ever falls below $8 million, the goodwill is “impaired” and the amount shown on the balance sheet must be adjusted downward and the write-off deducted from that year’s earnings. Some companies have found that this can make a nasty dent in profits. For example, when the new accounting rules were introduced, AOL was obliged to write down the value of its assets by $54 billion.

4. Some Tax Considerations

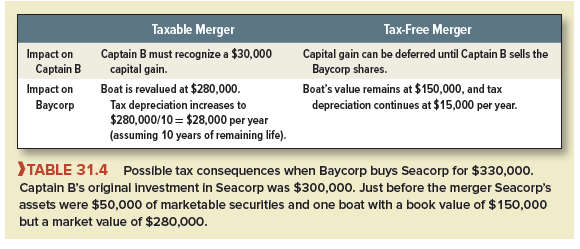

An acquisition may be either taxable or tax-free. If payment is in the form of cash, the acquisition is regarded as taxable. In this case the selling stockholders are treated as having sold their shares, and they must pay tax on any capital gains. If payment is largely in the form of shares, the acquisition is tax-free and the shareholders are viewed as exchanging their old shares for similar new ones; no capital gains or losses are recognized.

The tax status of the acquisition also affects the taxes paid by the merged firm afterward. After a tax-free acquisition, the merged firm is taxed as if the two firms had always been together. In a taxable acquisition, the assets of the selling firm are revalued, the resulting write-up or write-down is treated as a taxable gain or loss, and tax depreciation is recalculated on the basis of the restated asset values.

A very simple example will illustrate these distinctions. In 2008, Captain B forms Sea- corp, which purchases a fishing boat for $300,000. Assume, for simplicity, that the boat is depreciated for tax purposes over 20 years on a straight-line basis (no salvage value). Thus, annual depreciation is $300,000/20 = $15,000, and in 2018, the boat has a net book value of $150,000. But Captain B finds that, owing to careful maintenance, inflation, and good times in the local fishing industry, the boat is really worth $280,000. In addition, Seacorp holds $50,000 of marketable securities.

Now suppose that Captain B sells the firm to Baycorp for $330,000. The possible tax consequences of the acquisition are shown in Table 31.4. In this case, Captain B may ask for a tax-free deal to defer capital gains tax. But Baycorp can afford to pay more in a taxable deal because depreciation tax shields are larger.

5. Cross-Border Mergers and Tax Inversion

In 2013, the U.S pharmaceutical company Actavis took over Warner-Chilcott of Ireland. As part of the deal, the company announced that it would reincorporate in Ireland, where the corporate tax rate is 12.5%-much lower than the combined U.S. federal and state corporate tax rate at that time. One year later, the company acquired Forest Labs, which, as a result, also changed its headquarters to Ireland.

Both deals were examples of tax inversion. Before 2018, the United States taxed profits of U.S. corporations even if the profits were earned overseas.[6] Other countries had a territorial system and taxed only profits that were earned domestically. Therefore, when a U.S. corporation relocated abroad because of a merger, it still needed to pay U.S. tax on its U.S. profits, but it no longer paid U.S. tax on profits earned elsewhere. Since the corporate tax rate in the United States was much higher than in most other developed countries, there was a strong incentive for U.S. companies to move their domicile abroad. One way to do this was to arrange to be acquired by a foreign company.

Starting in 2018, the United States switched over to a territorial tax system. As a result, tax is paid on income earned in the United States but not on overseas income. Therefore, the incentive to change the company’s domicile by merger has disappeared.

It’s hard to find knowledgeable people on this topic, but you sound like you know what you’re talking about! Thanks