This importance of comparative advantage in global supply chains was recognized by Adam Smith in The Wealth of Nations when he stated, “If a foreign country can supply us with a commodity cheaper than we ourselves can make it, better buy it of them with some part of the produce of our own industry, employed in a way in which we have some advantage.” Cost reduction by moving production to low-cost countries is typically mentioned among the top reasons for a supply chain to become global. The challenge, however, is to quantify the benefits (or comparative advantage) of offshore production along with the reasons for this comparative advantage. Whereas many companies have taken advantage of cost reduction through offshoring, others have found the benefits of offshoring to low-cost countries to be far less than anticipated—and, in some cases, nonexistent. The increases in transportation costs between 2000 and 2011 have had a significant negative impact on the perceived benefits of offshoring. Companies have failed to gain from offshoring for two primary reasons: (1) focusing exclusively on unit cost rather than total cost when making the offshoring decision and (2) ignoring critical risk factors. In this section, we focus on dimensions along which total landed cost needs to be evaluated when making an offshoring decision.

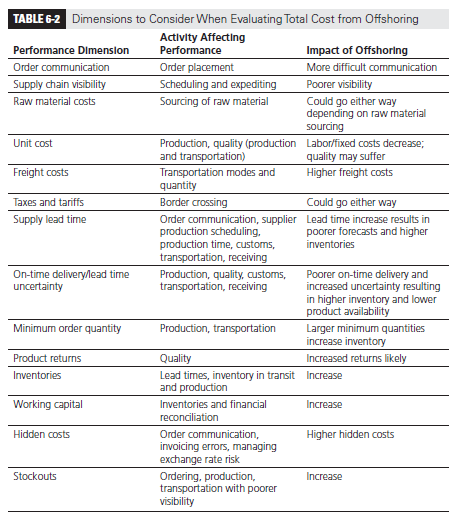

The significant dimensions of total cost can be identified by focusing on the complete sourcing process when offshoring. It is important to keep in mind that a global supply chain with offshoring increases the length and duration of information, product, and cash flows. As a result, the complexity and cost of managing the supply chain can be significantly higher than anticipated. Table 6-2 identifies dimensions along which each of the three flows should be analyzed for the impact on cost and product availability.

Ferreira and Prokopets (2009) suggest that companies should evaluate the impact of offshoring on the following key elements of total cost:

- Supplier price: should link to costs from direct materials, direct labor, indirect labor, management, overhead, capital amortization, local taxes, manufacturing costs, and local regulatory compliance costs.

- Terms: costs are affected by net payment terms and any volume discounts.

- Delivery costs: include in-country transportation, ocean/air freight, destination transport, and packaging.

- Inventory and warehousing: include in-plant inventories, in-plant handling, plant warehouse costs, supply chain inventories, and supply chain warehousing costs.

- Cost of quality: includes cost of validation, cost of performance drop due to poorer quality, and cost of incremental remedies to combat quality drop.

- Customer duties, value-added taxes, local tax incentives.

- Cost of risk, procurement staff, broker fees, infrastructure (IT and facilities), and tooling and mold costs.

- Exchange rate trends and their impact on cost.

It is important to both quantify these factors carefully when making the offshoring decision and track them over time. As Table 6-2 indicates, unit cost reduction from low labor and fixed costs, along with possible tax advantages, are likely to be the major benefit from offshoring, with almost every other factor being negative. In some instances, the substitution of labor for capital can provide a benefit when offshoring. For example, auto and auto parts plants in India are designed with much greater labor content than similar manufacturing in developed countries to lower fixed costs. The benefit of lower labor cost, however, is unlikely to be significant for a manufactured product if labor cost is a small fraction of total cost. It is also the case that in several low-cost countries, such as China and India, labor costs have escalated significantly. As mentioned by Goel et al. (2008), wage inflation in China averaged 19 percent in dollar terms between 2003 and 2008 compared to around 3 percent in the United States. During the same period, transportation costs increased by a significant amount (ocean freight costs increased 135 percent between 2005 and 2008) and the Chinese yuan strengthened relative to the dollar (by about 18 percent between 2005 and 2008). The net result was that offshoring manufactured products from the United States to China looked much less attractive in 2008 than in 2003.

In general, offshoring to low-cost countries is likely to be most attractive for products with high labor content, large production volumes, relatively low variety, and low transportation costs relative to product value. For example, a company producing a large variety of pumps is likely to find that offshoring the production of castings for a common part across many pumps is likely to be much more attractive than the offshoring of highly specialized engineered parts.

Given that global sourcing tends to increase transportation costs, it is important to focus on reducing transportation content for successful global sourcing. Suitably designed components can facilitate much greater density when transporting products. IKEA has designed modular products that are assembled by the customer. This allows the modules to be shipped flat in high density, lowering transportation costs. Similarly, Nissan redesigned its globally sourced components so that they can be packed more tightly when shipping. The use of supplier hubs can be effective if several components are being sourced globally from different locations. Many manufacturers have created supplier hubs in Asia that are fed by each of their Asian suppliers. This allows for a consolidated shipment to be sent from the hub rather than several smaller shipments being sent from each supplier. More sophisticated flexible policies that allow for direct shipping from the supplier when volumes are high, coupled with consolidated shipping through a hub when volumes are low, can be effective in lowering transportation cost.

It is also important to perform a careful review of the production process to decide which parts are to be offshored. For example, a small American jewelry manufacturer wanted to offshore manufacturing to Hong Kong for a piece of jewelry. Raw material in the form of gold sheet was sourced in the United States. The first step in the manufacturing process was the stamping of the gold sheet into a suitable-sized blank. This process generated about 40 percent waste, which could be recycled to produce more gold sheet. The manufacturer faced the choice of stamping in the United States or Hong Kong. Stamping in Hong Kong would incur lower labor cost but higher transportation cost and would require more working capital because of the delay before the waste gold could be recycled. A careful analysis indicated that it was cheaper for the stamping tools to be installed at the gold sheet supplier in the United States. Stamping at the gold sheet supplier reduced transportation cost because only usable material was shipped to Hong Kong. More importantly, this decision reduced working capital requirement because the waste gold from stamping was recycled within two days.

One of the biggest challenges with offshoring is the increased risk and its potential impact on cost. This challenge is exacerbated if a company uses an offshore location that is primarily targeting low costs to absorb all the uncertainties in its supply chain. In such a context, it is often much more effective to use a combination of an offshore facility that is given predictable, high-volume work along with an onshore or near-shore facility that is designed specifically to handle most of the fluctuation. Companies using only an offshore facility often find themselves carrying extra inventory and resorting to air freight because of the long and variable lead times. The presence of a flexible onshore facility that absorbs all the variation can often lower total landed cost by eliminating expensive freight and significantly reducing the amount of inventory carried in the supply chain.

Source: Chopra Sunil, Meindl Peter (2014), Supply Chain Management: Strategy, Planning, and Operation, Pearson; 6th edition.

I am not very fantastic with English but I get hold this rattling easy to interpret.