Investors buy or sell shares of common stock. Companies often buy or sell entire businesses or major stakes in businesses. For example, we have noted BHP Billiton’s plans to sell its U.S. shale business. Both BHP and potential bidders were doing their best to value that business by discounted cash flow.

DCF models work just as well for entire businesses as for shares of common stock. It doesn’t matter whether you forecast dividends per share or the total free cash flow of a business. Value today always equals future cash flow discounted at the opportunity cost of capital.

1. Valuing the Concatenator Business

Rumor has it that Establishment Industries is interested in buying your company’s concatenator manufacturing operation. Your company is willing to sell if it can get the full value of this rapidly growing business. The problem is to figure out what its true present value is.

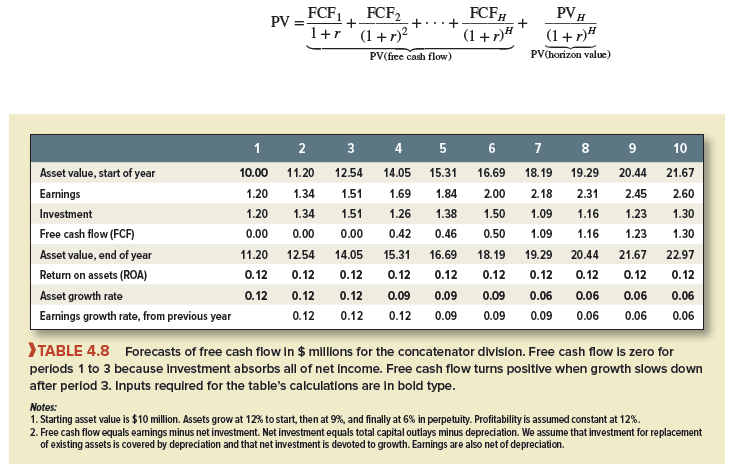

Table 4.8 gives a forecast of free cash flow (FCF) for the concatenator business. Free cash flow is the amount of cash that a firm can pay out to investors after paying for all investments necessary for growth. As we will see, free cash flow can be negative for rapidly growing businesses.

Table 4.8 is similar to Table 4.5, which forecasted earnings and dividends per share for Growth-Tech, based on assumptions about Growth-Tech’s equity per share, return on equity, and the growth of its business. For the concatenator business, we also have assumptions about assets, profitability—in this case, after-tax operating earnings relative to assets—and growth. Growth starts out at a rapid 12% per year, then falls in two steps to a moderate 6% rate for the long run. The growth rate determines the net additional investment required to expand assets, and the profitability rate determines the earnings thrown off by the business.

Free cash flow, the fourth line in Table 4.8, is equal to the firm’s earnings less any new investment expenditures. Free cash flow is zero in years 1 to 3, even though the parent company is investing over $4 million during this period.

Are the early zeros for free cash flow a bad sign? No: Free cash flow is zero because the business is growing rapidly, not because it is unprofitable. Rapid growth is good news, not bad, because the business is earning 12%, 2 percentage points over the 10% cost of capital. If the business could grow at 20%, Establishment Industries and its stockholders would be happier still, although growth at 20% would mean still higher investment and negative free cash flow.

2. Valuation Format

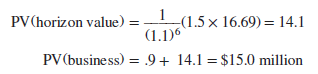

The value of a business is usually computed as the discounted value of free cash flows out to a valuation horizon (H), plus the forecasted value of the business at the horizon, also discounted back to present value. That is,

Of course, the concatenator business will continue after the horizon, but it’s not practical to forecast free cash flow year by year to infinity. PVH stands in for free cash flow in periods H + 1, H + 2, and so on.

Valuation horizons are often chosen arbitrarily. Sometimes the boss tells everybody to use 10 years because that’s a round number. We will try year 6, because growth of the concatenator business seems to settle down to a long-run trend after year 7.

3. Estimating Horizon Value

There are two common approaches to estimating horizon value. One uses valuation by comparables, based on P/E, market-to-book, or other ratios. The other uses DCF. We will start with valuation by comparables.

Horizon Value Based on P/E Ratios Suppose you can observe stock prices for good comparables, that is, for mature manufacturing companies whose scale, risk, and growth prospects today roughly match those projected for the concatenator business in year 6.[1] Suppose further that these companies tend to sell at price-earnings ratios of about 11. Then you could reasonably guess that the price-earnings ratio of a mature concatenator operation will likewise be 11. That implies:

![]()

The present value of the business up to the horizon is $.9 million.Therefore

PV (business) = .9 + 13.5 = $14.4 million

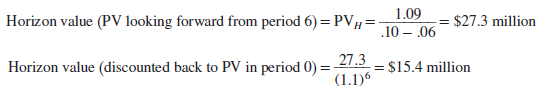

Horizon Value Based on Market-Book Ratios Suppose also that the market-book ratios of the sample of mature manufacturing companies tend to cluster around 1.5. If the concatenator business market-book ratio is 1.5 in year 6,

It’s easy to poke holes in these last two calculations. Book value, for example, is often a poor measure of the true value of a company’s assets. It can fall far behind actual asset values when there is rapid inflation, and it often entirely misses important intangible assets, such as your patents for concatenator design. Earnings may also be biased by inflation and a long list of arbitrary accounting choices. Finally, you never know when you have found a sample of truly similar companies to use as comparables.

But remember, the purpose of discounted cash flow is to estimate market value—to estimate what investors would pay for a stock or business. When you can observe what they actually pay for similar companies, that’s valuable evidence. Try to figure out a way to use it. One way to use it is through valuation by comparables, based on price-earnings or market-book ratios. Valuation rules of thumb, artfully employed, sometimes beat a complex discounted- cash-flow calculation hands down.

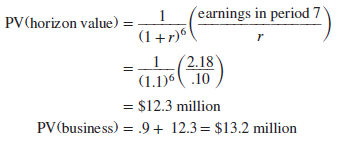

Horizon Value Based on DCF Now let us try the constant-growth DCF formula. This requires free cash flow for year 7, which we have at $1.09 million from Table 4.8; a long-run growth rate, which appears to be 6%; and a discount rate, which some high-priced consultant has told us is 10%. Therefore,

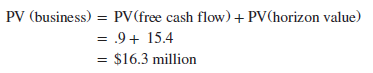

The PV of the near-term free cash flows is $.9 million. Thus the present value of the concatenator division is

Now, are we done? Well, the mechanics of this calculation are perfect. But doesn’t it make you just a little nervous to find that 94% of the value of the business rests on the horizon value? Moreover, a little checking shows that horizon value can change dramatically in response to small changes in the assumed long-term growth rate.

Suppose the growth rate is 7% instead of 6%. That means that asset value has to grow by an extra 1% per year, requiring extra investment of $.18 million in period 7, which reduces FCF7 to $.91 million. Horizon value increases to PVH = $30.3 million in year 6 and to $17.1 million discounted to year zero. The PV of the concatenator business increases from $16 .3 million to $.9 + 17.1 = $18.0 million.

Warning 1: When you use the constant-growth DCF formula to calculate horizon value, always remember that faster growth requires increased investment, which reduces free cash flow. Slower growth requires less investment, which increases free cash flow.

So 7% instead of 6% growth increases PV by $18.0 – 16.3 = $1.7 million. Why? We did not ignore warning 1: We accounted for the increased investment required for faster growth. Therefore the additional investment in periods 7 and beyond must have generated additional positive NPV. In other words, we must have assumed expanded growth opportunities and added more PVGO to the value of the business.

Notice in Table 4.8 that the return on assets (ROA) is forecasted at 12% forever, 2 percentage points higher than the assumed discount rate of 10%. Thus, every dollar invested in period 7 and beyond generates positive NPV and adds to horizon value and the PV of the business.

But is it realistic to assume that any business can keep on growing and making positive- NPV investments forever? Sooner or later you and your competitors will be on an equal footing. You may still be earning a superior return on past investments, but you will find that introductions of new products or attempts to expand profits from existing products trigger vigorous resistance from competitors who are just as smart and efficient as you are. When that time comes, the NPV of subsequent investments will average out to zero. After all, PVGO is positive only when investments can be expected to earn more than the cost of capital.

Warning 2: Always check to see whether horizon value includes post-horizon PVGO. You can check on warning 2 by changing the assumed long-term growth rate. If a higher growth rate increases horizon value—after you have taken care to respect warning 1—then you are assuming post-horizon PVGO. Is it realistic to assume that the firm can earn more than the cost of capital in perpetuity? If not, adjust your forecasts accordingly.

There is an easy way to calculate horizon value if post-horizon PVGO is zero. Recall that PV equals the capitalized value of next period’s earnings plus PVGO:

![]()

If PVGO = 0 at the horizon period H, then,

![]()

In other words, when the competition catches up and the firm can only earn its cost of equity on new investment, the price-earnings ratio will equal 1/r, because PVGO disappears.

This latest formula for PVH is still DCF. We are valuing the business as if assets and earnings will not grow after the horizon date.[2] (The business probably will grow, but the growth can be ignored, because it will add no net value if PVGO goes to zero.) With no growth, there is no net investment,[3] and all of earnings ends up as free cash flow.

Therefore, we can calculate the horizon value at period 6 as the present value of a level stream of earnings starting in period 7 and continuing indefinitely. The resulting value for the concatenator business is:

A Value Range for the Concatenator Business We now have four estimates of what Establishment Industries ought to pay for the concatenator business. The estimates reflect four different methods of estimating horizon value. There is no best method, although we like the last method, which forces managers to remember that sooner or later competition catches up.

Our calculated values for the concatenator business range from $13.2 to $16.3 million, a difference of about $3 million. The width of the range may be disquieting, but it is not unusual. Discounted-cash-flow formulas only estimate market value, and the estimates change as forecasts and assumptions change. Managers cannot know market value for sure until an actual transaction takes place.

4. Free Cash Flow, Dividends, and Repurchases

We assumed that the concatenator business was a division of your company, not a freestanding corporation. But suppose it was a separate corporation with 1 million shares outstanding. How would we calculate price per share? Simple: Calculate the PV of the business and divide by 1 million. If we decide that the business is worth $16.3 million, the price per share is $16.30.

If the concatenator business were a public Concatenator Corp., with no other assets and operations, it could pay out its free cash flow as dividends. Dividends per share would be the free cash flow shown in Table 4.8 divided by 1 million shares: zero in periods 1 to 3, then $.42 per share in period 4, $.46 per share in period 5, etc.

We mentioned stock repurchases as an alternative to cash dividends. If repurchases are important, it’s often simpler to value total free cash flow than dividends per share. Suppose Concatenator Corp. decides not to pay cash dividends. Instead, it will pay out all free cash flow by repurchasing shares. The market capitalization of the company should not change because shareholders as a group will still receive all free cash flow.

Perhaps the following intuition will help. Suppose you own all of the 1 million Concatena- tor shares. Do you care whether you get free cash flow as dividends or by selling shares back to the firm? Your cash flows in each future period will always equal the free cash flows shown in Table 4.8. Your DCF valuation of the company will, therefore, depend on the free cash flows, not on how they are distributed.

Chapter 16 covers the choice between cash dividends and repurchases (including tax issues and other complications). But you can see why it’s attractive to value a company as a whole by forecasting and discounting free cash flow. You don’t have to ask how free cash flow will be paid out. You don’t have to forecast repurchases.

It’s truly a nice and helpful piece of info. I’m glad that you just shared this useful info with us. Please keep us informed like this. Thank you for sharing.