Why might prices depart from fundamental values? Some believe that the answer lies in behavioral psychology. People are not 100% rational 100% of the time. This shows up in investors’ attitudes to risk and the way they assess probabilities.

- Attitudes toward risk. Psychologists have observed that, when making risky decisions, people are particularly loath to incur losses. It seems that investors do not focus solely on the current value of their holdings, but look back at whether their investments are showing a profit or a loss. For example, if I sell my holding of IBM stock for $10,000, I may feel on top of the world if the stock only cost me $5,000, but I will be much less happy if it had cost $11,000. This observation is the basis for prospect theory.[1] Prospect theory states that (a) the value investors place on a particular outcome is determined by the gains or losses that they have made since the asset was acquired or the holding last reviewed, and (b) investors are particularly averse to the possibility of even a very small loss and need a high return to compensate for it.

The pain of loss seems also to depend on whether it comes on the heels of earlier losses. Once investors have suffered a loss, they may be even more concerned not to risk a further loss. Conversely, just as gamblers are known to be more willing to make large bets when they are ahead, so investors may be more prepared to run the risk of a stock market dip after they have enjoyed a run of unexpectedly high returns.[2] If they do then suffer a small loss, they at least have the consolation of still being ahead for the year.

When we discussed portfolio theory in Chapters 7 and 8, we pictured investors as forward-looking only. Past gains or losses were not mentioned. All that mattered was the investor’s current wealth and the expectation and risk of future wealth. We did not allow for the possibility that Nicholas would be elated because his investment is in the black, while Nicola with an equal amount of wealth would be despondent because hers is in the red.

- Beliefs about probabilities. Most investors do not have a PhD in probability theory and may make systematic errors in assessing the probability of uncertain events. Psychologists have found that, when judging possible future outcomes, individuals tend to look back at what happened in a few similar situations. As a result, they are led to place too much weight on a small number of recent events. For example, an investor might judge that an investment manager is particularly skilled because he has “beaten the market” for three years in a row or that three years of rapidly rising prices are a good indication of future profits from investing in the stock market. The investor may not stop to reflect on how little one can learn about expected returns from three years’ experience.

Most individuals are also too conservative—that is, too slow to update their beliefs in the face of new evidence. People tend to update their beliefs in the correct direction, but the magnitude of the change is less than rationality would require.

Another systematic bias is overconfidence. For example, an American small business has just a 35% chance of surviving for five years. Yet the great majority of entrepreneurs think that they have a better than 70% chance of success.[3] Similarly, most investors think they are better-than-average stock pickers. Two speculators who trade with each other cannot both make money, but nevertheless, they may be prepared to continue trading because each is confident that the other is the patsy.[4] Overconfidence also shows up in the certainty that people express about their judgments. They consistently overestimate the odds that the future will turn out as they say and underestimate the chances of unlikely events.

You can see how these behavioral characteristics may help to explain the Japanese and dot-com bubbles. As prices rose, they generated increased optimism about the future and stimulated additional demand. The more that investors racked up profits, the more confident they became in their views and the more willing they became to bear the risk that next month might not be so good.

1. Sentiment

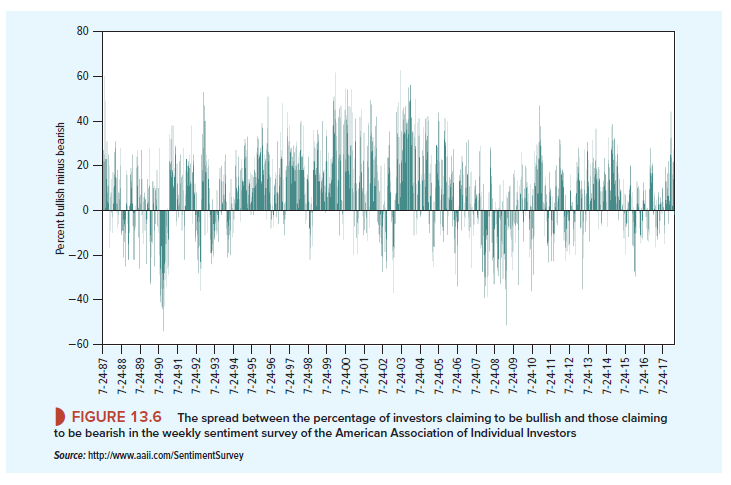

Behavioral economists stress the importance of investor sentiment in determining stock prices, and they point to evidence of major swings in sentiment. For example, every week the American Association of Individual Investors surveys its members and asks them whether they are bullish, bearish, or neutral on the stock market over the next six months. Anyone who believed that all the good or bad news was already reflected in stock prices would tick the neutral box. But you can see from Figure 13.6 that private investors swing quite strongly between being bullish or bearish. In January 2000, at the height of the dot-com boom, a massive 75% of investors said they were bullish, 62% more than claimed to be bearish. Perhaps these periods of bullishness and bearishness may explain the short-term momentum effect that we commented on earlier.

2. Limits to Arbitrage

It is not difficult to believe that amateur investors may sometimes be caught up in a scatty whirl of irrational exuberance.[6] But there are plenty of hard-headed professional investors managing huge sums of money. Why don’t these investors bail out of overpriced stocks and force their prices down to fair value? One reason is that there are limits to arbitrage—that is, limits on the ability of the rational investors to exploit market inefficiencies.

Strictly speaking, arbitrage means an investment strategy that guarantees superior returns without any risk. In practice, arbitrage is defined more casually as a strategy that exploits market inefficiency and generates superior returns if and when prices return to fundamental values. Such strategies can be very rewarding, but they are rarely risk-free.

In an efficient market, if prices get out of line, then arbitrage forces them back. The arbitrageur buys the underpriced securities (pushing up their prices) and sells the overpriced securities (pushing down their prices). The arbitrageur earns a profit by buying low and selling high and waiting for prices to converge to fundamentals. Thus, arbitrage trading is often called convergence trading.

But arbitrage is harder than it looks. Trading costs can be significant, and some trades are difficult to execute. For example, suppose that you identify an overpriced security that is not in your existing portfolio. You want to “sell high,” but how do you sell a stock that you don’t own? It can be done, but you have to sell short.

To sell a stock short, you borrow shares from another investor’s portfolio, sell them, and then wait hopefully until the price falls and you can buy the stock back for less than you sold it for. If you’re wrong and the stock price increases, then sooner or later you will be forced to repurchase the stock at a higher price (therefore at a loss) to return the borrowed shares to the lender. But if you’re right and the price does fall, you repurchase, pocket the difference between the sale and repurchase prices, and return the borrowed shares. Sounds easy, once you see how short selling works, but there are costs and fees to be paid, and in some cases, you will not be able to find shares to borrow.[7]

The perils of selling short were dramatically illustrated in 2008. Given the gloomy outlook for the automobile industry, several hedge funds decided to sell Volkswagen (VW) shares short in the expectation of buying them back at a lower price. Then in a surprise announcement, Porsche revealed that it had effectively gained control of 74% of VW’s shares. Since a further 20% was held by the state of Lower Saxony, there was not enough stock available for the short sellers to buy back. As they scrambled to cover their positions, the price of VW stock rose in just two days from €209 to a high of €1,005, making VW the most highly valued company in the world. Although the stock price drifted rapidly down, those short-sellers who were caught in the short squeeze suffered large losses.

The VW example illustrates that the most important limit to arbitrage is the risk that prices will diverge even further before they converge. Thus, an arbitrageur has to have the guts and resources to hold on to a position that may get much worse before it gets better. Take another look at the relative prices of Royal Dutch and Shell T&T in Figure 13.4. Suppose that you were a professional money manager in 1980, when Royal Dutch was about 12% below parity. You decided to buy Royal Dutch, sell Shell T&T short, and wait confidently for prices to converge to parity. It was a long wait. The first time you would have seen any profit on your position was in 1983. In the meantime, the mispricing got worse, not better. Royal Dutch fell to more than 30% below parity in mid-1981. Therefore, you had to report a substantial loss on your “arbitrage” strategy in that year. You were fired and took up a new career as a used-car salesman.

The demise in 1998 of Long Term Capital Management (LTCM) provides another example of the problems with convergence trades. LTCM, one of the largest and most profitable hedge funds of the 1990s, believed that interest rates in the different eurozone countries would converge when the euro replaced the countries’ previous currencies. LTCM had taken massive positions to profit from this convergence, as well as massive positions designed to exploit other pricing discrepancies. After the Russian government announced a moratorium on some of its debt payments in August 1998, there was great turbulence in the financial markets, and many of the discrepancies that LTCM was betting on suddenly got much larger.[8] LTCM was losing hundreds of millions of dollars daily. The fund’s capital was nearly gone when the Federal Reserve Bank of New York arranged for a group of LTCM’s creditor banks to take over LTCM’s remaining assets and shut down what was left in an orderly fashion.

LTCM’s sudden meltdown has not prevented rapid growth in the hedge fund industry in the 2000s. If hedge funds can push back the limits to arbitrage and avoid the kinds of problems that LTCM ran into, markets will be more efficient going forward. But asking for complete efficiency is probably asking too much. Prices can get out of line and stay out if the risks of an arbitrage strategy outweigh the expected returns.

3. Incentive Problems and the Financial Crisis of 2008-2009

The limits to arbitrage open the door to individual investors with built-in biases and misconceptions that can push prices away from fundamental values. But there can also be incentive problems that get in the way of a rational focus on fundamentals. We illustrate with a brief look at the financial crisis in 2008 and 2009.

Although U.S. house prices had risen nearly threefold in the decade to 2006, few homeowners foresaw a collapse in the price of their home. After all, the average house price in the U.S. had not fallen since the Great Depression of the 1930s. But in 2006, the bubble burst. By March 2009, U.S. house prices had fallen by nearly a third from their peak.[9]

How could such a boom and crash arise? In part because banks, credit rating agencies, and other financial institutions all had distorted incentives. Purchases of real estate are generally financed with mortgage loans from banks. In most parts of the United States, borrowers can default on their mortgages with relatively small penalties. If property prices fall, they can simply walk away. But if prices rise, they make money. Thus, borrowers may be willing to take large risks, especially if the fraction of the purchase price financed with their own money is small.

Why, then, are banks willing to lend money to people who are bound to default if property prices fall significantly? Since the borrowers benefited most of the time, they were willing to pay attractive up-front fees to banks to get mortgage loans. But the banks could pass on the default risk to somebody else by packaging and reselling the mortgages as mortgage-backed securities (MBSs). Many MBS buyers assumed that they were safe investments because the credit rating agencies said so. As it turned out, the credit ratings were a big mistake. (The rating agencies introduced another agency problem because issuers paid the agencies to rate the MBS issues, and the agencies consulted with issuers over how MBS issues should be structured.)

The “somebody else” was also the government. Many subprime mortgages were sold to FNMA and FHLMC (“Fannie Mae” and “Freddie Mac”). These were private corporations with a special advantage: government credit backup. (The backup was implicit but quickly became explicit when Fannie and Freddie got into trouble in 2008. The U.S. Treasury had to take them over.) Thus, these companies were able to borrow at artificially low rates, channeling money into the mortgage market.

The government was also on the hook because large banks that held subprime MBSs were “too big to fail” in a financial crisis. So the original incentive problem—the temptation of home buyers to take out a large mortgage and hope for higher real estate prices—was never corrected. The government could have cut its exposure by reining in Fannie and Freddie before the crisis but did not do so, perhaps because the government was happy to see more people able to buy their own homes.

Agency and incentive problems are widespread in the financial services industry. In the United States and many other countries, people engage financial institutions such as pension funds and mutual funds to invest their money. These institutions are the investors’ agents, but the agents’ incentives do not always match the investors’ interests. Just as with real estate, these agency relationships can lead to mispricing, and potentially bubbles.[10]

25 Jun 2021

25 Jun 2021

23 Jun 2021

24 Jun 2021

24 Jun 2021

25 Jun 2021