1. Corporate Bonds and Default Risk

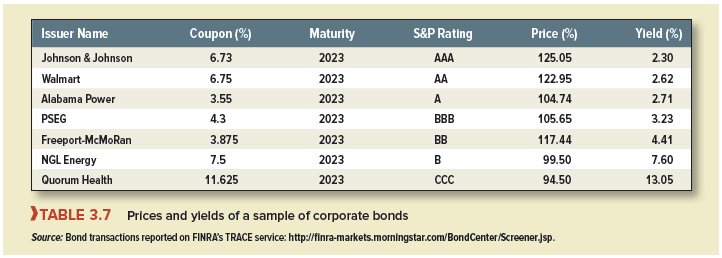

Look at Table 3.7, which shows the yields to maturity on a sample of corporate bonds. Notice that the bonds all mature in 2023, but their yields to maturity differ dramatically. With a yield of 13.0%, the bonds of Quorum Health appeared to offer a mouth-watering rate of return. However, the company had been operating at a loss and had substantial debts. Investors foresaw that there was a good chance that the company would default and that they would not get their money back. Thus, the payments promised to the bondholders represent a best-case scenario: The firm will never pay more than the promised cash flows, but in hard times, it may pay less. This risk applies in some measure to all corporate bonds, but investors were much more confident that Johnson & Johnson would be able to service its debt and this is reflected in the low yield on its bonds.

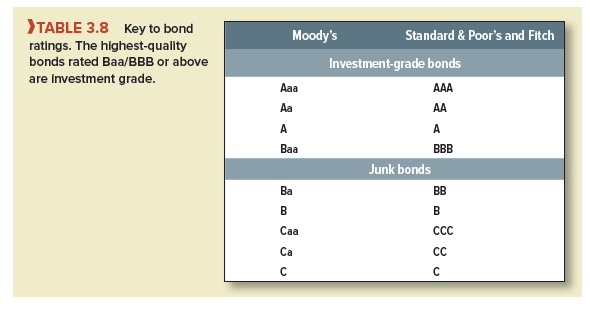

The safety of most corporate bonds can be judged from bond ratings provided by Moody’s, Standard & Poor’s (S&P), and Fitch. Table 3.8 lists the possible bond ratings in declining order of quality. For example, the bonds that receive the highest Standard & Poor’s rating are known as AAA (or “triple A”) bonds. Then come AA (double A), A, BBB bonds, and so on. Bonds rated BBB and above are called investment grade, while those with a rating of BB or below are referred to as speculative grade, high-yield, or junk bonds. Notice that the bonds in the first four rows of Table 3.7 are all investment-grade bonds; the rest are junk bonds.

It is rare for highly rated bonds to default. However, when an investment-grade bond does go under, the shock waves are felt in all major financial centers. For example, in May 2001, World- Com sold $11.8 billion of bonds with an investment-grade rating. About one year later, WorldCom filed for bankruptcy, and its bondholders lost more than 80% of their investment. For these bondholders, the agencies that had assigned investment-grade ratings were not the flavor of the month.

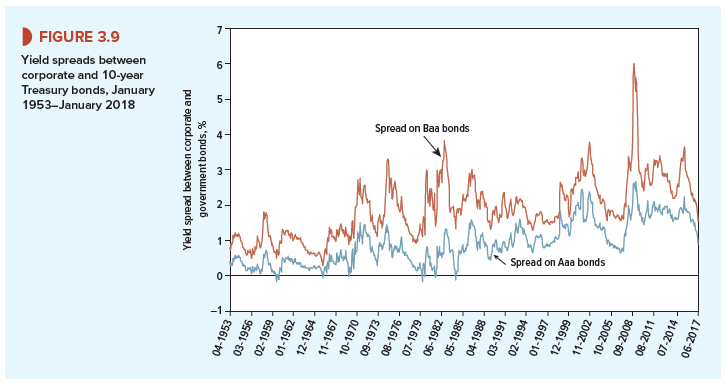

Because of the risk of default, yields on corporate bonds are higher than those of government bonds. For example, Figure 3.9 shows the yield spread of corporate bonds against U.S. Treasuries. Notice that the spreads widen as safety falls off. Notice also how spreads vary over time. On average, the spread on Baa bonds has been about 2%, but it widened to more than 6% during the credit crunch of 2007 to 2009.

1. Sovereign Bonds and Default Risk

When investors buy corporate bonds or a bank lends to a company, they worry about the possibility of default and spend considerable time and effort assessing differences in credit risk. By contrast, when the U.S. government issues dollar bonds, investors can generally be confident that those bonds will be repaid in full and on time. Of course, bondholders don’t know what that money will be worth. Governments have a nasty habit of reducing the real value of their debts by inflationary policies.

Although sovereign debt is generally less risky than corporate debt, we should not leave you with the impression that it is always safe even in money terms. Indeed, as the nearby Finance in Practice box explains, even in the United States investors in government bonds have had their slightly scary moments. Countries do occasionally default on their debts and, when they do so, the effects can be catastrophic. We will look briefly at three circumstances in which countries may default.

Foreign Currency Debt Most government bond defaults have occurred when a foreign government borrows dollars. In these cases investors worry that in some future crisis the government may run out of taxing capacity and may not be able to come up with enough dollars to repay the debt. This worry shows up in bond prices and yields to maturity. For example, in 2001 the Argentinian government defaulted on $82 billion of debt. As the prospect of default loomed, the price of Argentinian bonds slumped, and the promised yield climbed to more than 40 percentage points above the yield on U.S. Treasuries. Argentina has plenty of company. Since 1970, there have been more than 100 occasions that sovereign governments have defaulted on their foreign currency bonds.

Own Currency Debt If a government borrows in its own currency, there is less likelihood of default. After all, the government can always print the money needed to repay the bonds. Very occasionally, governments have chosen to default on their domestic debt rather than create the money to pay it off. That was the case in Russia in the summer of 1998, when political instability combined with a slump in oil prices, declining government revenues, and pressure on the exchange rate. By August yields on government ruble bonds had reached 200% and it no longer made sense for Russia to create the money to service its debt. That month the government devalued the ruble and defaulted on its domestic ruble debt.

Eurozone Debt The 19 countries in the eurozone do not even have the option of printing money to service their domestic debts; they have given up control over their own money supply to the European Central Bank. This was to pose a major problem for the Greek government, which had amassed a massive €330 billion (or about $440 billion) of debt. In May 2010, other eurozone governments and the International Monetary Fund (IMF) rushed to Greece’s aid, but investors were unconvinced that their assistance would be sufficient, and the yield on 10-year Greek government debt climbed to nearly 27%. In 2012, in return for a further bailout package, investors in Greek bonds were obliged to accept a write-down of some $100 billion in the value of their bonds. It was the largest ever sovereign default. However, the difficulties for Greece were by no means over. The rescue package required it to adopt an austerity policy that resulted in a sharp fall in national income and considerable hardship for the Greek people. The country was also unable to escape from its large debt burden. It missed a payment on its debt to the IMF in 2015, and two years later, despite a further bailout, was back in crisis mode.

The sovereign debt crisis in Europe was not confined to Greece. Cyprus also delayed repayment of its bonds, and the Irish and Portuguese government debt was down-rated to junk level. Investors joked that, instead of offering a risk-free return, eurozone government bonds just offered a return-free risk.

My brother suggested I would possibly like this website. He was once entirely right. This submit actually made my day. You can not believe simply how so much time I had spent for this information! Thank you!