Monitoring can’t be perfect. Therefore, compensation plans must be designed to attract competent managers and to give them the right incentives.

For U.S. public companies, compensation is the responsibility of the compensation committee of the board of directors. The Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC) and New York Stock Exchange (NYSE) require that all directors on the compensation committee be independent—that is, not managers or employees and not linked to the company by some other relationship (e.g., a lucrative consulting contract) that would undercut their independence. The committee typically hires outside consultants to advise on compensation trends and on compensation levels in peer companies.

You can see how the information provided by outside consultants may cause compensation to creep up. The problem is that compensation committees don’t want to approve below- average compensation. But if every firm wants to be above-average, then the average will ratchet up.[1]

Once the compensation package is approved by the committee, it is described in an annual Compensation Discussion and Analysis (CD&A), which is sent to shareholders along with director nominations and the company’s 10-K filing. (The 10-K is the annual report to the SEC.) In January 2011, the SEC gave shareholders a nonbinding say-on-pay vote on the CD&A at least once every three years.[2] The occasional no vote on management compensation is a disagreeable wake-up call for managers and directors. For example, when the shareholders of auto supplier BorgWarner voted “no” in 2015, the company made changes to its compensation program and cut the CEO’s incentive award by $2.4 million.

To reinforce these safeguards we now have two consulting companies, ISS and Glass Lewis, that review CD&As for thousands of companies, looking especially at pay- for-performance standards. Their clients are mostly institutional investors, who seek advice on how to vote. (A mutual fund or pension fund may own shares in hundreds of companies. The fund may decide to outsource the analysis of CD&As to a company that specializes in governance issues.)

1. Compensation Facts and Controversies

Studies of executive pay in the United States suggest three general features:

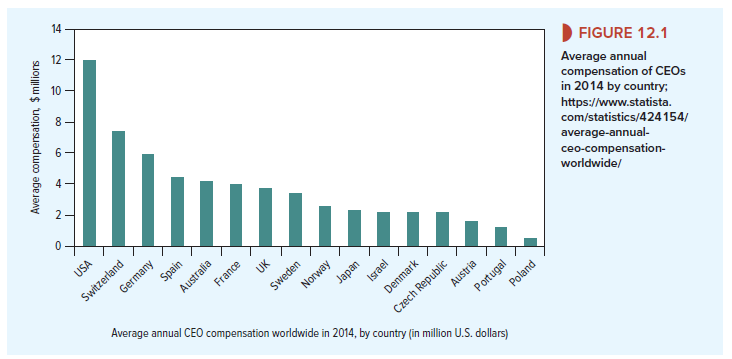

- As you can see from Figure 12.1, U.S. CEOs tend to be more highly paid than their opposite numbers in other countries. On average, they get double the pay of German CEOs and more than five times the pay of Japanese CEOs.

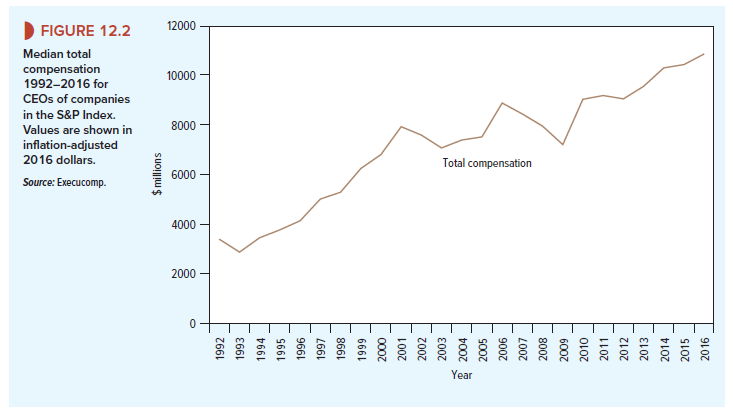

- Figure 12.2 shows that average compensation in the United States has risen much more rapidly than inflation. Between 1992 and 2016, total compensation for the CEOs of companies in the Standard & Poor’s (S&P) Index has more than tripled in real terms.12

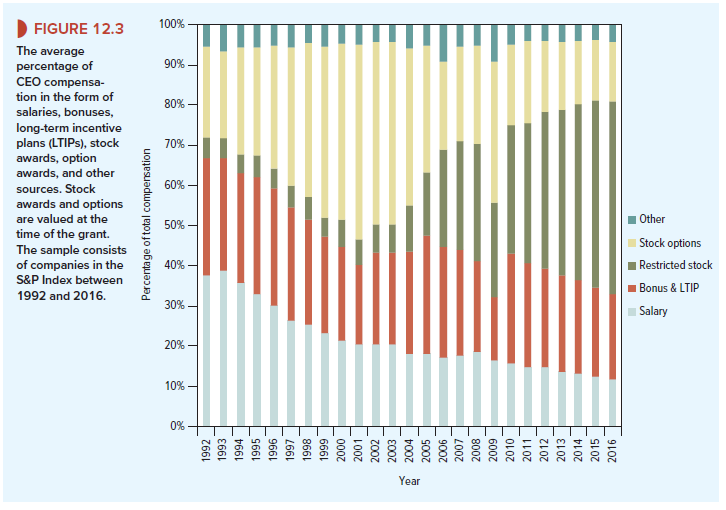

- Figure 12.3 shows that only 12% of compensation for these CEOs comes from salary. The remainder comes from bonuses, stock grants, stock options, and other performance-linked incentives. This proportion of incentive-based compensation has increased sharply and is much higher than in other countries.

We look first at the size of the pay package. Then we turn to its contents.

High levels of CEO pay undoubtedly encourage CEOs to work hard and (perhaps more important) offer an attractive carrot to lower-level managers who hope to become CEOs. But there has been widespread concern about “excessive” pay, especially pay for mediocre performance. For example, Robert Nardelli received a $210 million severance package on leaving The Home Depot, and Henry McKinnell received almost $200 million on leaving Pfizer. Both CEOs left behind troubled and underperforming companies. You can imagine the newspaper headlines.

Those headlines were even bigger in 2008 when it was revealed that generous bonuses were to be paid to the senior management of banks that had been bailed out by the government. Merrill Lynch hurried through $3.6 billion in bonuses, including $121 million to just four executives, only days before Bank of America finalized its deal to buy the collapsing firm with the help of taxpayer money. “Bonuses for Boneheads” was the headline in Forbes magazine.

It is easy to point to cases where poorly performing managers have received unjustifiably large payouts. But is there a more general problem? Perhaps high levels of pay simply reflect a shortage of talent. After all, CEOs are not alone in earning large sums. The earnings of top professional athletes are equally mouthwatering. The LA Dodgers’ Clayton Kershaw was paid $33 million in 2017. The Dodgers must have believed that it was worth paying for a star who would win games and fill up the ballpark.

If star managers are as rare as star baseball players, corporations may need to pay up for CEO talent. Suppose that a superior CEO can add 1% to the value of a large corporation with a market capitalization of $10 billion. One percent on a stock market value of $10 billion is $100 million. If the CEO can really deliver, then a pay package of, say, $20 million per year sounds like a bargain.[3]

There is also a less charitable explanation of managerial pay. This view stresses the close links between the CEO and the other members of the board of directors. If directors are too chummy with the CEO, they may find it difficult to get tough when it comes to setting compensation packages.

So we have two views of the level of managerial pay. One is that it results from arms- length contracting in a tight market for managerial talent. The other is that poor governance and weak boards allow excessive pay. There is evidence for and against both views. For example, CEOs are not the only group to have seen their compensation increase rapidly in recent years. Corporate lawyers, sports stars, and celebrity entertainers have all increased their share of national income, even though their compensation is determined by arms-length negotiation.[4] However, the shortage-of-talent argument cannot account for wide disparities in pay. For example, compare the CEO of Ford (compensation of $22 million in 2016) to the CEO of Toyota (compensation of about $3 million) or to Fed Chairman Jerome Powell ($200,000). It is difficult to argue that Ford’s CEO delivered the most value or had the most difficult and important job.

2. The Economics of Incentive Compensation

The amount of compensation may be less important than how it is structured. The compensation package should encourage managers to maximize shareholder wealth.

Compensation could be based on input (e.g., the manager’s effort) or on output (income or value added as a result of the manager’s decisions). But input is difficult to measure.

How can outside investors observe effort? They can check that the manager clocks in on time, but hours worked does not measure true effort. (Is the manager facing up to difficult and stressful choices, or is he or she just burning time with routine meetings, travel, and paperwork?)

Because effort is not observable, compensation must be based on output—that is, on verifiable results. Trouble is, results depend not just on the manager’s contribution, but also on events outside the manager’s control. Unless you can separate out the manager’s contribution, you face a difficult trade-off. You want to give the manager high-powered incentives, so that he or she does very well when the firm does very well and poorly when the firm underperforms. But suppose the firm is a cyclical business that always struggles in recessions. Then high-powered incentives will force the manager to bear business cycle risk that is not his or her fault.

There are limits to the risks that managers can be asked to bear. So the result is a compromise. Firms do link managers’ pay to performance, but fluctuations in firm value are shared by managers and shareholders. Managers bear some of the risks that are beyond their control, and shareholders bear some of the agency costs when managers fail to maximize firm value.

Most major companies around the world now link part of their executive pay to the performance of the companies’ stock.[5] Sometimes these incentive schemes constitute the major part of the manager’s compensation pay. For example, for the 2017 fiscal year, Larry Ellison, who was CEO of the business software giant Oracle Corporation, received total compensation estimated at $21 million. Only $1 of that amount was salary. The lion’s share was in the form of stock and option grants. Moreover, as founder of Oracle, Ellison holds more than 1 billion shares in the firm. No one can say for certain how hard Ellison would have worked with a different compensation package. But one thing is clear: He has a huge personal stake in the success of the firm—and in increasing its market value.

Stock options give managers the right (but not the obligation) to buy their company’s shares in the future at a fixed exercise price. Usually, the exercise price is set equal to the company’s stock price on the day the options are granted. If the company performs well and stock price increases, the manager can buy shares and cash in on the difference between the stock price and the exercise price. If the stock price falls, the manager leaves the options unexercised and hopes for compensation through another channel.

The popularity of stock options was encouraged by U.S. accounting rules, which permitted companies to grant stock options without recognizing any immediate compensation expense. The rules allowed companies to value options at the excess of the stock price over the exercise price on the grant date. But the exercise price was almost always set equal to the stock price on that date. Thus, the excess was zero and the stock options were valued at zero. (We show how to calculate the actual value of options in Chapters 20 and 21.) So companies could grant lots of options at no recorded cost and with no reduction in accounting earnings. Naturally, accountants and investors were concerned because earnings were overstated in greater numbers as the volume of option grants increased. After years of controversy, the accounting rules were changed in 2006. U.S. corporations are now required to value executive stock options more realistically and to deduct these values as a compensation expense.

Options also used to have a tax advantage in the United States. Since 1994, compensation of more than $1 million has been considered unreasonable and is not a tax-deductible expense. However, until 2018 there was no restriction on performance-based compensation such as stock options. This exemption was removed by the Tax Cuts and Jobs Act of December 2017.

If you look back at Figure 12.3, you will see that the form of incentive compensation has also undergone significant change. During the 1990s, there was a surge in the use of stock options, and by the year 2000, almost half of a CEO’s compensation was typically in the form of options. More recently, companies have increasingly rewarded management with restricted shares or, more commonly, with performance shares. In the former case, the manager receives a fixed number of shares at the end of a vesting period as long as he or she is still with the company. In the latter case, the number of shares that the manager receives is typically related to his or her performance in the interim.

You can see the advantages of tying compensation to stock price either by the grant of options or stock. When a manager works hard to increase the price, he or she helps shareholders as well as herself.The stock price is a noisy, but objective measure of a firm’s financial performance. It is also a forward-looking measure; it incorporates the value of future earnings and future growth opportunities (PVGO). Thus a manager can be rewarded today for ensuring that his or her firm has a good shot at a prosperous future.

But compensation tied to stock price can also have unpleasant side effects. We have already noted how compensation based on stock price forces managers to bear risks that are outside their control. Think of the CEO of an oil company. The company’s earnings and stock price depend on worldwide oil prices. When oil prices took off as they did in 1974, 1980 and the early 2000s, did oil-industry CEOs get an extra compensation for being in the right industry at the right time? Bertrand and Mullainathan found that the answer was Yes. Compensation in the oil industry was closely linked to the level of oil prices. But they also found that the link was weaker when shareholders with large blocks of stock sat on the board of directors. It seems that these shareholders resisted large compensation awards that were based just on good luck.[6]

Some companies do attempt to take out the effect of luck by measuring and rewarding performance relative to industry peers. For example, the electric utility Entergy bases part of its incentive compensation on how well Entergy stock performs relative to the Philadelphia Index of 20 of the largest U.S. utilities.

A second problem with performance-related pay is that stock prices depend on investors’ expectations of future earnings, and rates of return depend on how well the company performs relative to expectations. Suppose a company announces the appointment of an outstanding new manager. The stock price leaps up in anticipation of improved performance. If the new manager then delivers exactly the good performance that investors expected, the stock will earn only a normal rate of return. In this case, a compensation scheme linked to the stock return after the manager starts would fail to recognize the manager’s special contribution.

Stock options can also encourage excessive risk taking. For example, when stock prices fall precipitously, as they did for many firms in the crisis of 2007-2009, existing stock options can be far “underwater” and nearly worthless. Managers holding these options may be tempted to gamble for redemption.

3. The Specter of Short-Termism

The fourth imperfection may be the most serious. Managers whose pay depends on the stock price are tempted to withhold bad news or manage reported earnings. They are also tempted to postpone or cancel valuable investment projects if the projects would depress earnings in the short run.

CEOs of public companies face constant scrutiny. Much of that scrutiny focuses on earnings. Security analysts forecast earnings per share (EPS), and investors, security analysts, and professional portfolio managers wait to see whether the company can meet or beat the forecasts. Not meeting the forecasts can be a big disappointment.

Monitoring by security analysts and portfolio managers can help constrain agency problems. But CEOs complain about the “tyranny of EPS” and the apparent short-sightedness of the stock market. (The British call it short-termism.) Of course, the stock market is not systematically short-sighted. If it were, growth companies would not sell at the high price- earnings ratios observed in practice.[7] Nevertheless, the pressure on CEOs to generate steady, predictable growth in earnings is real.

CEOs complain about this pressure, but do they do anything about it? Unfortunately the answer appears to be yes, according to Graham, Harvey, and Rajgopal, who surveyed about 400 senior managers.[8] Most of the managers said that accounting earnings were the single most important number reported to investors. Most admitted to adjusting their firms’ operations and investments to manage earnings. For example, 80% were willing to decrease discretionary spending in R&D, advertising, or maintenance if necessary to meet earnings targets. Many managers were also prepared to defer or reject investment projects with positive NPVs.

There is a good deal of evidence that firms do indeed manage their earnings. For example, Degeorge, Patel, and Zeckhauser studied a large sample of earnings announcements.[9] With remarkable regularity, earnings per share either met or beat security analysts’ forecasts, but only by a few cents. CFOs appeared to report conservatively in good times, building a stockpile of earnings that could be reported later. The rule, it seems, is Make sure that you report sufficiently good results to keep analysts happy, and, if possible, keep something back for a rainy day.[10]

How much value was lost because of such adjustments? For a healthy, profitable company, spending a little less on advertising or deferring a project start for a few months may cause no significant damage. But we cannot endorse any sacrifice of fundamental shareholder value done just to manage earnings.

We may condemn earnings management, but in practice it’s hard for CEOs and CFOs to break away from the crowd. Graham and his coauthors explain it this way:[11]

The common belief is that a well-run and stable firm should be able to “produce the numbers”. . . even in a year that is somewhat down. Because the market expects firms to be able to hit or slightly exceed earnings targets, and on average firms do just this, problems can arise when a firm does not deliver. . . . The market might assume that not delivering [reveals] potentially serious problems (because the firm is apparently so near the edge that it cannot produce the dollars to hit earnings . . .). As one CFO put it, “if you see one cockroach, you immediately assume that there are hundreds behind the walls.”

Thus, we have a cockroach theory explaining why stock prices sometimes fall sharply when a company’s earnings fall short, even if the shortfall is only a penny or two.

Of course, private firms do not have to worry about earnings management—which could help explain the increasing number of firms that have been bought out and returned to private ownership. (We discuss “going private” in Chapters 15, 32, and 33.) Firms in some other countries, where quarterly earnings reports are not required and governance is more relaxed, may find it easier to invest for the long run. But such firms will probably accumulate more agency problems. We wish there were simple answers to these trade-offs.

Whats up very nice web site!! Guy .. Excellent .. Superb .. I’ll bookmark your site and take the feeds also…I am satisfied to seek out so many helpful information right here within the submit, we need work out more strategies in this regard, thank you for sharing.

It’s best to participate in a contest for one of the best blogs on the web. I’ll recommend this site!