To carry on business, a corporation needs an almost endless variety of real assets. These do not drop free from a blue sky; they need to be paid for. The corporation pays for its real assets by selling claims on them and on the cash flow that they will generate. These claims are called financial assets or securities. Take a bank loan as an example. The bank provides the corporation with cash in exchange for a financial asset, which is the corporation’s promise to repay the loan with interest. An ordinary bank loan is not a security, however, because it is held by the bank and is not traded in financial markets.

Take a corporate bond as a second example. The corporation sells the bond to investors in exchange for the promise to pay interest on the bond and to pay off the bond at its maturity. The bond is a financial asset, and also a security, because it can be held and traded by many investors in financial markets. Securities include bonds, shares of stock, and a dizzying variety of specialized instruments. We describe bonds in Chapter 3, stocks in Chapter 4, and other securities in later chapters.

This suggests the following definitions:

Investment decision = purchase of real assets

Financing decision = sale of securities and other financial assets

But these equations are too simple. The investment decision also involves managing assets already in place and deciding when to shut down and dispose of assets when they are no longer profitable. The corporation also has to manage and control the risks of its investments. The financing decision includes not just raising cash today but also meeting its obligations to banks, bondholders, and stockholders that have contributed financing in the past. For example, the corporation has to repay its debts when they become due. If it cannot do so, it ends up insolvent and bankrupt. Sooner or later the corporation will also want to pay out cash to its shareholders.[1]

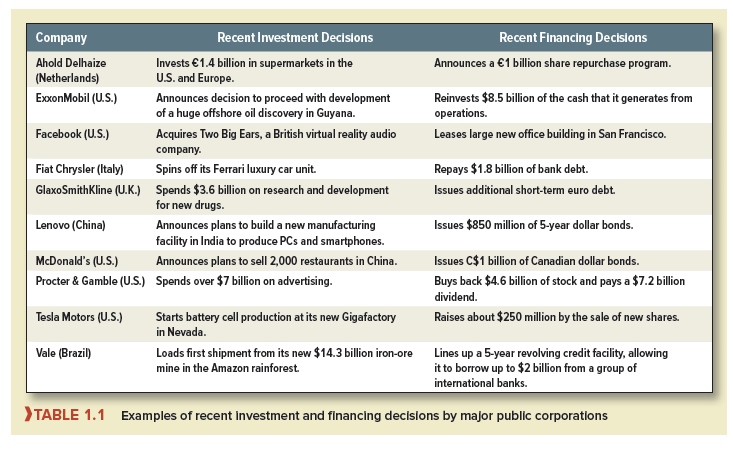

Let’s go to more specific examples. Table 1.1 lists 10 corporations from all over the world. We have chosen very large public corporations that you are probably already familiar with. You may have used Facebook to chat with your friends, eaten at McDonald’s, or used Crest toothpaste.

1. Investment Decisions

The second column of Table 1.1 shows an important recent investment decision for each corporation. These investment decisions are often referred to as capital budgeting or capital expenditure (CAPEX) decisions because most large corporations prepare an annual capital budget listing the major projects approved for investment. Some of the investments in Table 1.1, such as ExxonMobil’s new oil field or Lenovo’s factory, involve the purchase of tangible assets—assets that you can touch and kick. However, corporations also need to invest in intangible assets, such as research and development (R&D), advertising, and computer software. For example, GlaxoSmithKline and other major pharmaceutical companies invest billions every year on R&D for new drugs. Similarly, consumer goods companies such as Procter & Gamble invest huge sums in advertising and marketing their products. These outlays are investments because they build know-how, brand recognition, and reputation for the long run.

Today’s capital investments generate future cash returns. Sometimes the cash inflows last for decades. For example, many U.S. nuclear power plants, which were initially licensed by the Nuclear Regulatory Commission to operate for 40 years, are now being re-licensed for 20 more years and may be able to operate efficiently for 80 years overall.

Of course, not all investments have such distant payoffs. For example, Walmart spends about $50 billion each year to stock up its stores and warehouses before the holiday season. The company’s return on this investment comes within months as the inventory is drawn down and the goods are sold.

In addition, financial managers know (or quickly learn) that cash returns are not guaranteed. An investment could be a smashing success or a dismal failure. For example, the Iridium communications satellite system, which offered instant telephone connections worldwide, soaked up $5 billion of investment before it started operations in 1998. It needed 400,000 subscribers to break even, but attracted only a small fraction of that number. Iridium defaulted on its debt and filed for bankruptcy in 1999. The Iridium system was sold a year later for just $25 million. (Iridium has recovered and is now profitable, however.)[2]

Among the contenders for the all-time worst investment was Hewlett-Packard’s (HP) purchase of the British software company Autonomy. HP paid $11.1 billion for Autonomy. Just 13 months later, it wrote down the value of this investment by $8.8 billion. HP claimed that it was misled by improper accounting at Autonomy. Nevertheless, the acquisition was a disastrous investment, and HP’s CEO was fired in short order.

In some cases, the costs and risks of an investment can be huge. For example, the cost of developing the Gorgon natural gas field in Australia has been estimated at more than $40 billion. But do not think of the financial manager as making such large investments on a daily basis. Most investment decisions are smaller and simpler, such as the purchase of a truck, machine tool, or computer system. Corporations make thousands of these smaller investment decisions every year. The cumulative amount of small investments can be just as large as that of the occasional big investments.

Also, financial managers do not make major investment decisions in solitary confinement. They may work as part of a team of engineers and managers from manufacturing, marketing, and other business functions.

2. Financing Decisions

The third column of Table 1.1 lists a recent financing decision by each corporation. A corporation can raise money from lenders or from shareholders. If it borrows, the lenders contribute the cash, and the corporation promises to pay back the debt plus a fixed rate of interest. If the shareholders put up the cash, they do not get a fixed return, but they hold shares of stock and therefore get a fraction of future profits and cash flow. The shareholders are equity investors, who contribute equity financing. The choice between debt and equity financing is called the capital structure decision. Capital refers to the firm’s sources of long-term financing.

The financing choices available to large corporations seem almost endless. Suppose the firm decides to borrow. Should it borrow from a bank or borrow by issuing bonds that can be traded by investors? Should it borrow for 1 year or 20 years? If it borrows for 20 years, should it reserve the right to pay off the debt early? Should it borrow in Paris, receiving and promising to repay euros, or should it borrow dollars in New York?

Corporations raise equity financing in two ways. First, they can issue new shares of stock. The investors who buy the new shares put up cash in exchange for a fraction of the corporation’s future cash flow and profits. Second, the corporation can take the cash flow generated by its existing assets and reinvest that cash in new assets. In this case the corporation is reinvesting on behalf of existing stockholders. No new shares are issued.

What happens when a corporation does not reinvest all of the cash flow generated by its existing assets? It may hold the cash in reserve for future investment, or it may pay the cash back to its shareholders. Table 1.1 shows that Procter & Gamble paid back $4.6 billion to its stockholders by repurchasing shares. This was in addition to $7.2 billion paid out as cash dividends. The decision to pay dividends or repurchase shares is called the payout decision. We cover payout decisions in Chapter 16.

In some ways, financing decisions are less important than investment decisions. Financial managers say that “value comes mainly from the asset side of the balance sheet.” In fact, the most successful corporations sometimes have the simplest financing strategies. Take Microsoft as an example. It is one of the world’s most valuable corporations. In December 2017, Microsoft shares traded for about $88 each. There were 7.7 billion shares outstanding. Therefore Microsoft’s overall market value—its market capitalization or market cap—was $88 X 7.7 = $680 billion. Where did this market value come from? It came from Microsoft’s product development, from its brand name and worldwide customer base, from its research and development, and from its ability to make profitable future investments. The value did not come from sophisticated financing. Microsoft’s financing strategy is very simple: It carries no debt to speak of and finances almost all investment by retaining and reinvesting cash flow.

Financing decisions may not add much value, compared with good investment decisions, but they can destroy value if they are stupid or if they are ambushed by bad news. For example, after a consortium of investment companies bought the energy giant TXU in 2007, the company took on an additional $50 billion of debt. This may not have been a stupid decision, but it did prove nearly fatal. The consortium did not foresee the expansion of shale gas production and the resulting sharp fall in natural gas and electricity prices. In 2014, the company (renamed Energy Future Holdings) was no longer able to service its debts and filed for bankruptcy.

Business is inherently risky. The financial manager needs to identify the risks and make sure they are managed properly. For example, debt has its advantages, but too much debt can land the company in bankruptcy, as the buyers of TXU discovered. Companies can also be knocked off course by recessions, by changes in commodity prices, interest rates and exchange rates, or by adverse political developments. Some of these risks can be hedged or insured, however, as we explain in Chapters 26 and 27.

3. What Is a Corporation?

We have been referring to “corporations.” Before going too far or too fast, we need to offer some basic definitions. Details follow in later chapters.

A corporation is a legal entity. In the view of the law, it is a legal person that is owned by its shareholders. As a legal person, the corporation can make contracts, carry on a business, borrow or lend money, and sue or be sued. One corporation can make a takeover bid for another and then merge the two businesses. Corporations pay taxes—but cannot vote!

In the United States, corporations are formed under state law, based on articles of incorporation that set out the purpose of the business and how it is to be governed and operated.3 For example, the articles of incorporation specify the composition and role of the board of directors.4 A corporation’s directors are elected by the shareholders. They choose and advise top management and must sign off on important corporate actions, such as mergers and the payment of dividends to shareholders.

A corporation is owned by its shareholders but is legally distinct from them. Therefore the shareholders have limited liability, which means that they cannot be held personally responsible for the corporation’s debts. When the U.S. financial corporation Lehman Brothers failed in 2008, no one demanded that its stockholders put up more money to cover Lehman’s massive debts. Shareholders can lose their entire investment in a corporation, but no more.

When a corporation is first established, its shares may be privately held by a small group of investors, such as the company’s managers and a few backers. In this case, the shares are not publicly traded and the company is closely held. Eventually, when the firm grows and new shares are issued to raise additional capital, its shares are traded in public markets such as the New York Stock Exchange. These corporations are known as public companies. Most well-known corporations in the U.S. are public companies with widely dispersed shareholdings. In other countries, it is more common for large corporations to remain in private hands, and many public companies may be controlled by just a handful of investors. The latter category includes such well-known names as Volkswagen (Germany), Alibaba (China), Softbank (Japan), and the Swatch Group (Switzerland).

A large public corporation may have hundreds of thousands of shareholders, who own the business but cannot possibly manage or control it directly. This separation of ownership and control gives corporations permanence. Even if managers quit or are dismissed and replaced, the corporation survives. Today’s stockholders can sell all their shares to new investors without disrupting the operations of the business. Corporations can, in principle, live forever, and in practice, they may survive many human lifetimes. One of the oldest corporations is the Hudson’s Bay Company, which was formed in 1670 to profit from the fur trade between northern Canada and England. The company still operates as one of Canada’s leading retail chains.

The separation of ownership and control can also have a downside, for it can open the door for managers and directors to act in their own interests rather than in the stockholders’ interest. We return to this problem later in the chapter.

There are other disadvantages to being a corporation. One is the cost, in both time and money, of managing the corporation’s legal machinery. These costs are particularly burdensome for small businesses. There is also an important tax drawback to corporations in the United States. Because the corporation is a separate legal entity, it is taxed separately. So corporations pay tax on their profits, and shareholders are taxed again when they receive dividends from the company or sell their shares at a profit. By contrast, income generated by businesses that are not incorporated is taxed just once as personal income.

Almost all large and medium-sized businesses are corporations, but the nearby box describes how smaller businesses may be organized.

4. The Role of the Financial Manager

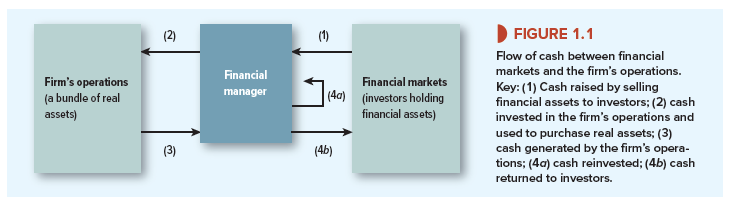

What is the essential role of the financial manager? Figure 1.1 gives one answer. The figure traces how money flows from investors to the corporation and back to investors again. The flow starts when cash is raised from investors (arrow 1 in the figure). The cash could come from banks or from securities sold to investors in financial markets. The cash is then used to pay for the real assets (capital investment projects) needed for the corporation’s business (arrow 2). Later, as the business operates, the assets produce cash inflows (arrow 3). That cash is either reinvested (arrow 4a) or returned to the investors who furnished the money in the first place (arrow 4b). Of course, the choice between arrows 4a and 4b is constrained by the promises made when cash was raised at arrow 1. For example, if the firm borrows money from a bank at arrow 1, it must repay this money plus interest at arrow 4b.

You can see examples of arrows 4a and 4b in Table 1.1. ExxonMobil financed its new projects by reinvesting earnings (arrow 4a). Procter & Gamble decided to return cash to shareholders by paying cash dividends and by buying back its stock (arrow 4b).

Notice how the financial manager stands between the firm and outside investors. On the one hand, the financial manager helps manage the firm’s operations, particularly by helping to make good investment decisions. On the other hand, the financial manager deals with investors—not just with shareholders but also with financial institutions such as banks and with financial markets such as the New York Stock Exchange.

Hello my loved one! I wish to say that this article is amazing, great written and come with approximately all important infos. I would like to look extra posts like this .