1. The Three Elements of Project Cash Flows

You can think of an investment project’s cash flow as composed of three elements:

Total cash flow = cash flow from capital investment

+ operating cash flow

+ cash flow from changes in working capital

Capital Investment To get a project off the ground, a company typically makes an up-front investment in plant, equipment, research, start-up costs, and diverse other outlays. This expenditure is a negative cash flow—negative because cash goes out the door.

When the project comes to an end, the company can either sell the plant and equipment or redeploy it elsewhere in its business. This salvage value (net of any taxes if the plant and equipment is sold) is a positive cash flow. However, remember our earlier comment that final cash flows can be negative if there are significant shutdown costs.

Operating Cash Flow Operating cash flow consists of the net increase in sales revenue brought about by the new project less outlays for production, marketing, distribution, and other incremental costs. Incremental taxes are likewise subtracted.

Operating cash flow = revenues – expenses – taxes

Many investments do not produce any additional revenues; they are simply designed to reduce the costs of the company’s existing operations. Such projects also contribute to the firm’s operating cash flow. The after-tax cost saving is a positive addition to the cash flow.

Don’t forget that the depreciation charge is not a cash flow. It affects the tax that the company pays, but the company does not send anyone a check for depreciation, and it should not be deducted when calculating operating cash flow.

Investment in Working Capital When a company builds up inventories of raw materials or finished products, this investment in inventories requires cash. Cash is also absorbed when customers are slow to pay their bills; in this case the firm makes an investment in accounts receivable. On the other hand, cash is preserved when the firm can delay paying its bills. Accounts payable are in a way a source of financing.

Investment in working capital, just like investment in plant and equipment, represents a negative cash flow. On the other hand, later in the project’s life, as inventories are sold and accounts receivable are collected, working capital is reduced and the firm enjoys a positive cash flow.

2. Forecasting the Fertilizer Project’s Cash Flows

As the newly appointed financial manager of International Mulch and Compost Company (IM&C), you are about to analyze a proposal for marketing guano as a garden fertilizer.

(IM&C’s planned advertising campaign features a rustic gentleman who steps out of a vegetable patch singing, “All my troubles have guano way.”)5

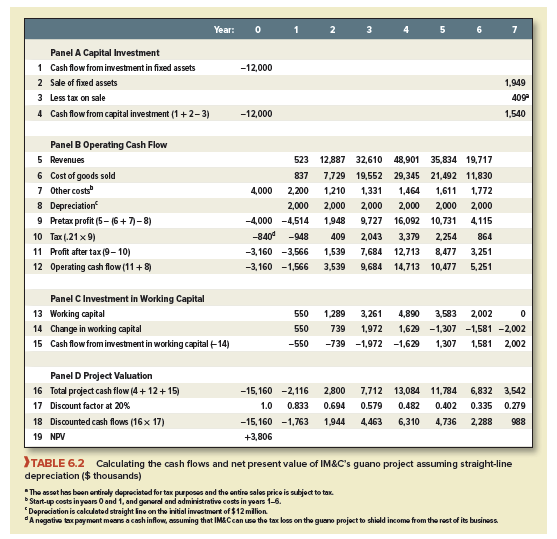

Table 6.2 shows the forecasted cash flows from the project. All the entries in the table are BEYOND THE PAGE nominal. In other words, the forecasts that you have been given take into account the likely effect of inflation on revenues and costs. We assume initially that for tax purposes the company uses straight-line depreciation. In other words, when it calculates each year’s taxable income, it deducts one-sixth of the initial investment.

The calculation in panel B of profit after tax is similar to the calculation in IM&C’s financial statements. There is one important difference. When calculating the depreciation figure in the published income statement, IM&C may choose to depreciate the plant and equipment to its likely salvage value. By contrast, IRS rules for calculating the company’s tax liability always assume that the plant and equipment has a salvage value of zero.

Capital Investment Rows 1 through 4 of Table 6.2 show the cash flows from the investment in fixed assets. The project requires an investment of $12 million in plant and machinery.

IM&C expects to sell the equipment in year 7 for $1.949 million. Any difference between this figure and the book value of the equipment is a taxable gain. By year 7, IM&C has fully depreciated the equipment, so the company will be taxed on a capital gain of $1.949 million.

If the tax rate is 21%, the company will pay tax of .21 x 1.949 = $0.409 million, and the net cash flow from the sale of equipment will be 1.949 – 0.409 = $1.540 million. This is shown in rows 2 and 3 of the table.

Operating Cash Flow Panel B of Table 6.2 show the calculation of the operating cash flow from the guano project. Operating cash flow consists of revenues from the sale of guano less the cash expenses of production and any taxes. Taxes are calculated on profits net of depreciation. Thus, if the tax rate is 21%,

Tax = .21 x (sales – cash expenses – depreciation)

We assume in this first-pass table that the company uses straight-line depreciation. This means that, if the depreciable life of the equipment is six years, IM&C can deduct from profits one-sixth of the initial $12 million investment. Thus, row 8 shows that straight-line depreciation in each year is

Annual depreciation = (1/6 x 12.0) = $2.0 million

Pretax profits and taxes are shown in rows 9 and 10. For example, in year 2

Pretax profit = 12.887 – (7.729 + 1.210) – 2.000 = $1.948 million

Tax = .21 x 1.948 = $0.409 million

Once we have calculated taxes, it is a simple matter to calculate operating cash flow. Thus,

Operating cash flow in year 2 = revenues – cash expenses – taxes

= 12.887 – (7.729 + 1.210) – 0.409 = $3.539 million

Notice that, when calculating operating cash flow, we ignored the possibility that the project may be partly financed by debt. Following our earlier Rule 4, we did not deduct any debt proceeds from the original investment, and we did not deduct interest payments from the cash inflows. Standard practice forecasts cash flows as if the project is all-equity financed. Any additional value resulting from financing decisions is considered separately.

Investment in Working Capital You can see from Table 6.2 that working capital increases in the early and middle years of the project. Why is this? There are several possible reasons:

- Sales recorded on the income statement overstate actual cash receipts from guano shipments because sales are increasing and customers are slow to pay their bills. Therefore, accounts receivable increase.

- It takes several months for processed guano to age properly. Thus, as projected sales increase, larger inventories have to be held in the aging sheds.

- An offsetting effect occurs if payments for materials and services used in guano production are delayed. In this case accounts payable will increase.

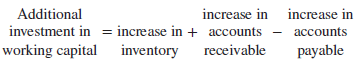

Thus, the additional investment in working capital can be calculated as:

There is an alternative to worrying about changes in working capital. You can estimate cash flow directly by counting the dollars coming in from customers and deducting the dollars going out to suppliers. You would also deduct all cash spent on production, including cash spent for goods held in inventory. In other words,

- If you replace each year’s sales with that year’s cash payments received from customers, you don’t have to worry about accounts receivable.

- If you replace cost of goods sold with cash payments for labor, materials, and other costs of production, you don’t have to keep track of inventory or accounts payable.

However, you would still have to construct a projected income statement to estimate taxes.

Project Valuation Rows 16 to 19 of Table 6.2 show the calculation of project NPV. Row 16 shows the total cash flow from IM&C’s project as the sum of the capital investment, operating cash flow, and investment in working capital. IM&C estimates the opportunity cost of capital for projects of this type as 20%.

Remember that to calculate the present value of a cash flow in year t you can either divide the cash flow by (1 + r)t or you can multiply by a discount factor that is equal to 1/(1 + r)t. Row 17 shows the discount factors for a 20% discount rate, and Row 18 multiplies the discount factor by the cash flow to give each flow’s present value. When all the cash flows are discounted and added up, the project is seen to offer a net present value of $3.806 million.

3. Accelerated Depreciation and First-Year Expensing

Depreciation is a noncash expense; it is important only because it reduces taxable income. It provides an annual tax shield equal to the product of depreciation and the marginal tax rate. In the case of IM&C:

Annual tax shield = depreciation x tax rate = 2,000 X .21 = 420.0, or $420,000.

The present value of these tax shields ($420,000 for six years) is $1,397,000 at a 20% discount rate.

In Table 6.2 we assumed that IM&C was required to use straight-line depreciation, which allowed it to write off a fixed proportion of the initial investment each year. This is the most common method of depreciation, but some countries, including the United States, permit firms to depreciate their investments more rapidly.

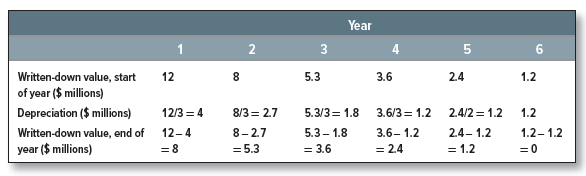

There are several different methods of accelerated depreciation. For example, firms may be allowed to use the double-declining-balance method. Suppose that IM&C is permitted to use double-declining-balance depreciation. In this case, it can deduct not one-sixth, but 2 x 1/6 = 1/3 of the remaining book value of the investment in each year.[2] Therefore, in year 1, it deducts depreciation of 12/3 = $4 million, and the written-down value of the equipment falls to 12 – 4 = $8 million. In year 2, IM&C deducts depreciation of 8/3 = $2.7 million, and the written-down value is further reduced to $8 – 2.7 = $5.3 million. In year 5, IM&C observes that depreciation would be higher if it could switch to straight-line depreciation and write off the balance of $2.4 million over the remaining two years of the equipment’s life. If this is permitted, IM&C’s depreciation allowance each year would be as follows:

The present value of the tax shields with double-declining-balance depreciation is $1.608 million, $212,000 million higher than if IM&C was restricted to straight-line depreciation.

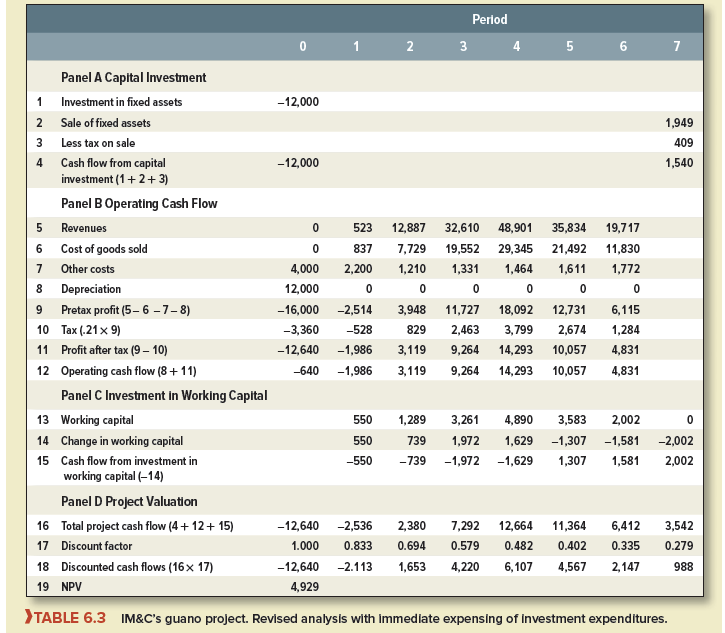

From 1986 to the end of 2017, U.S. companies used a slight variation of the doubledeclining balance method, called the modified accelerated cost recovery system (MACRS).[3] But the 2017 Tax Cuts and Jobs Act offered companies bonus depreciation sufficient to write off 100% of their investment expenditures in the year that they come on line. Table 6.3 recalculates the NPV of the guano project, assuming that the full $12 million investment can be depreciated immediately.

We initially assumed that the guano project could be depreciated straight-line over six years. This resulted in an NPV of $3.806 million. We then calculated that if IM&C could use the double-declining-balance method, NPV would increase by $212,000 to $4.018 million. Finally, Table 6.3 shows that full first-year expensing introduced in the 2017 tax reform would increase NPV further to $4.929 million.

4. Final Comments on Taxes

Two final comments. First, note that all of the guano project’s $12 million capital investment is in plant and equipment, which, under current U.S. tax law, can be expensed immediately. But suppose the project also requires an up-front R&D outlay of $500,000. Under the Tax Cuts and Jobs Act, R&D expenditures after 2021 cannot be expensed but must be written off over five years.

Second, all large U.S. corporations keep two separate sets of books, one for stockholders and one for the Internal Revenue Service (IRS). It is common to use straight-line depreciation on the stockholder books and accelerated depreciation on the tax books. The IRS doesn’t object to this, and it makes the firm’s reported earnings higher than if accelerated depreciation were used everywhere. There are many other differences between tax books and shareholder books.[4]

The financial analyst must be careful to remember which set of books he or she is looking at. In capital budgeting only the tax books are relevant, but to an outside analyst only the shareholder books are available.

5. Project Analysis

Let us review. Earlier in this section, you embarked on an analysis of IM&C’s guano project. You drew up a series of cash-flow forecasts assuming straight-line depreciation. Then you remembered accelerated depreciation and recalculated cash flows and NPV. Finally, you recognized that under the Tax Cuts and Jobs Act, IM&C could write off the capital expenditure in the year that it was incurred.

You were lucky to get away with just three NPV calculations. In real situations, it often takes several tries to purge all inconsistencies and mistakes. Then you may want to analyze some alternatives. For example, should you go for a larger or smaller project? Would it be better to market the fertilizer through wholesalers or directly to the consumer? Should you build 90,000-square-foot aging sheds for the guano in northern South Dakota rather than the planned 100,000-square-foot sheds in southern North Dakota? In each case, your choice should be the one offering the highest NPV. Sometimes the alternatives are not immediately obvious. For example, perhaps the plan calls for two costly, high-speed packing lines. But, if demand for guano is seasonal, it may pay to install just one high-speed line to cope with the base demand and two slower but cheaper lines simply to cope with the summer rush. You won’t know the answer until you have compared NPVs.

You will also need to ask some “what if clear” questions. How would NPV be affected if inflation rages out of control? What if technical problems delay start-up? What if gardeners prefer chemical fertilizers to your natural product? Managers employ a variety of techniques to develop a better understanding of how such unpleasant surprises could damage NPV. For example, they might undertake a sensitivity analysis, in which they look at how far the project could be knocked off course by bad news about one of the variables. Or they might construct different scenarios and estimate the effect of each on NPV. Another technique, known as break-even analysis, is to explore how far sales could fall short of forecast before the project goes into the red.

In Chapter 10, we practice using each of these “what if clear” techniques. You will find that project analysis is much more than one or two NPV calculations.[5]

Chapter 6 Making Investment Decisions with the Net Present Value Rule

6. Calculating NPV in Other Countries and Currencies

Our guano project was undertaken in the United States by a U.S. company. But the principles of capital investment are the same worldwide. For example, suppose that you are the financial manager of the German company, K.G.R. Okologische Naturdungemittel GmbH (KGR), that is faced with a similar opportunity to make a €10 million investment in Germany. What changes?

- KGR must also produce a set of cash-flow forecasts, but in this case the project cash flows are stated in euros, the eurozone currency.

- In developing these forecasts, the company needs to recognize that prices and costs will be influenced by the German inflation rate.

- Profits from KGR’s project are liable to the German rate of corporate tax, which is currently 15.8% plus a large municipal trade tax.

- KGR must use the German system of depreciation allowances. In common with many other countries, Germany requires firms to use the straight-line system. KGR, therefore, writes off one-sixth of the capital outlay each year.

- Finally, KGR discounts the project’s euro cash flows at the German cost of capital measured in euros.

Now suppose you are the financial manager of a U.S. company considering the same investment in Germany. You would go through exactly the same steps as KGR. You would not have to worry about U.S. taxes on your company’s German profits because the United States now has a territorial corporate income tax. You would probably convert the project NPV from euros to U.S. dollars, however, and you might use a different cost of capital. We discuss crossborder capital investment decisions in Chapter 27.

I like this site its a master peace ! Glad I found this on google .

I also conceive thus, perfectly pent post! .