What would you say if you were asked to name the seven most important ideas in finance? Here is our list.

1. Net Present Value

When you wish to know the value of a used car, you look at prices in the secondhand car market. Similarly, when you wish to know the value of a future cash flow, you look at prices quoted in the capital markets, where claims to future cash flows are traded (remember, those highly paid investment bankers are just secondhand cash-flow dealers). If you can buy cash flows for your shareholders at a cheaper price than they would have to pay in the capital market, you have increased the value of their investment.

This is the simple idea behind net present value (NPV). When we calculate an investment project’s NPV, we are asking whether the project is worth more than it costs. We are estimating its value by calculating what its cash flows would be worth if a claim on them were offered separately to investors and traded in the capital markets.

That is why we calculate NPV by discounting future cash flows at the opportunity cost of capital—that is, at the expected rate of return offered by securities having the same degree of risk as the project. In well-functioning capital markets, all equivalent-risk assets are priced to offer the same expected return. By discounting at the opportunity cost of capital, we calculate the price at which investors in the project could expect to earn that rate of return.

Like most good ideas, the net present value rule is “obvious when you think about it.” But notice what an important idea it is. The NPV rule allows thousands of shareholders, who may have vastly different levels of wealth and attitudes toward risk, to participate in the same enterprise and to delegate its operation to a professional manager. They give the manager one simple instruction: “Maximize net present value.”

2. The Capital Asset Pricing Model

Some people say that modern finance is all about the capital asset pricing model. That’s nonsense. If the capital asset pricing model had never been invented, our advice to financial managers would be essentially the same. The attraction of the model is that it gives us a manageable way of thinking about the required return on a risky investment.

Again, it is an attractively simple idea. There are two kinds of risk: risks that you can diversify away and those that you can’t. You can measure the nondiversifiable, or market, risk of an investment by the extent to which the value of the investment is affected by a change in the aggregate value of all the assets in the economy. This is called the beta of the investment. The only risks that people care about are the ones that they can’t get rid of—the nondiversifiable ones. This is why the required return on an asset increases in line with its beta.

Many people are worried by some of the rather strong assumptions behind the capital asset pricing model, or they are concerned about the difficulties of estimating a project’s beta. They are right to be worried about these things. In 10 or 20 years’ time, we may have much better theories than we do now.1 But we will be extremely surprised if those future theories do not still insist on the crucial distinction between diversifiable and nondiversifiable risks—and that, after all, is the main idea underlying the capital asset pricing model.

3. Efficient Capital Markets

The third fundamental idea is that security prices accurately reflect available information and respond rapidly to new information as soon as it becomes available. This efficient-market theory comes in three flavors, corresponding to different definitions of “available information.” The weak form (or random-walk theory) says that prices reflect all the information in past prices. The semistrong form says that prices reflect all publicly available information, and the strong form holds that prices reflect all acquirable information.

Don’t misunderstand the efficient-market idea. It doesn’t say that there are no taxes or costs; it doesn’t say that there aren’t some clever people and some stupid ones. It merely implies that competition in capital markets is very tough—there are no money machines or arbitrage opportunities, and security prices reflect the true underlying values of assets.

Extensive empirical testing of the efficient-market hypothesis began around 1970. By 2018, after almost 50 years of work, the tests have uncovered dozens of statistically significant anomalies. Sorry, but this work does not translate into dozens of ways to make easy money. Superior returns are elusive. For example, only a few mutual fund managers can generate superior returns for a few years in a row, and then only in small amounts.2 Statisticians can beat the market, but real investors have a much harder time of it. And on that essential matter there is now widespread agreement.3

4. Value Additivity and the Law of Conservation of Value

The principle of value additivity states that the value of the whole is equal to the sum of the values of the parts. It is sometimes called the law of the conservation of value.

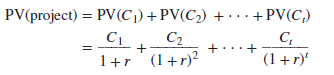

When we appraise a project that produces a succession of cash flows, we always assume that values add up. In other words, we assume

We similarly assume that the sum of the present values of projects A and B equals the present value of a composite project AB.[1] But value additivity also means that you can’t increase value by putting two whole companies together unless you thereby increase the total cash flow. In other words, there are no benefits to mergers solely for diversification.

5. Capital Structure Theory

If the law of the conservation of value works when you add up cash flows, it must also work when you subtract them.[2] Therefore, financing decisions that simply divide up operating cash flows don’t increase overall firm value. This is the basic idea behind Modigliani and Miller’s famous proposition 1: In perfect markets changes in capital structure do not affect value. As long as the total cash flow generated by the firm’s assets is unchanged by capital structure, value is independent of capital structure. The value of the whole pie does not depend on how it is sliced.

Of course, MM’s proposition is not The Answer, but it does tell us where to look for reasons why capital structure decisions may matter. Taxes are one possibility. Debt provides a corporate interest tax shield, and this tax shield may more than compensate for any extra personal tax that the investor has to pay on debt interest. Also, high debt levels may spur managers to work harder and to run a tighter ship. But debt has its drawbacks if it leads to costly financial distress.

6. Option Theory

In everyday conversation, we often use the word “option” as synonymous with “choice” or “alternative”; thus, we speak of someone as “having a number of options.” In finance, option refers specifically to the opportunity to trade in the future on terms that are fixed today. Smart managers know that it is often worth paying today for the option to buy or sell an asset tomorrow.

Since options are so important, the financial manager needs to know how to value them. Finance experts always knew the relevant variables—the exercise price and the exercise date of the option, the risk of the underlying asset, and the rate of interest. But it was Black and Scholes who first showed how these can be put together in a usable formula.

The Black-Scholes formula was developed for simple call options and does not directly apply to the more complicated options often encountered in corporate finance. But Black and Scholes’s most basic ideas—for example, the risk-neutral valuation method implied by their formula—work even where the formula doesn’t. Valuing the real options described in Chapter 22 may require extra number crunching but no extra concepts.

7. Agency Theory

A modern corporation is a team effort involving a number of players, such as managers, employees, shareholders, and bondholders. For a long time, economists used to assume without question that all these players acted for the common good, but in the last 30 years, they have had a lot more to say about the possible conflicts of interest and how companies attempt to overcome such conflicts. These ideas are known collectively as agency theory.

Consider, for example, the relationship between the shareholders and the managers. The shareholders (the principals) want managers (their agents) to maximize firm value. In the United States, the ownership of many major corporations is widely dispersed, and no single shareholder can check on the managers or reprimand those who are slacking. So, to encourage managers to pull their weight, firms seek to tie the managers’ compensation to the value that they have added. For those managers who persistently neglect shareholders’ interests, there is the threat that their firm will be taken over and they will be turfed out.

Some corporations are owned by a few major shareholders, and therefore, there is less distance between ownership and control. For example, the families, companies, and banks that hold or control large stakes in many German companies can review top management’s plans and decisions as insiders. In most cases, they have the power to force changes as necessary. However, hostile takeovers in Germany are rare.

We discussed the problems of management incentives and corporate control in Chapters 12, 14, 32, and 33, but they were not the only places in the book where agency issues arose. For example, in Chapters 18 and 24, we looked at some of the conflicts that arise between shareholders and bondholders, and we described how loan agreements try to anticipate and minimize these conflicts.

Are these seven ideas exciting theories or plain common sense? Call them what you will, they are basic to the financial manager’s job. If, by reading this book, you really understand these ideas and know how to apply them, you have learned a great deal.

I’m not positive where you’re getting your info, however good topic. I must spend some time studying more or working out more. Thank you for fantastic information I was searching for this info for my mission.