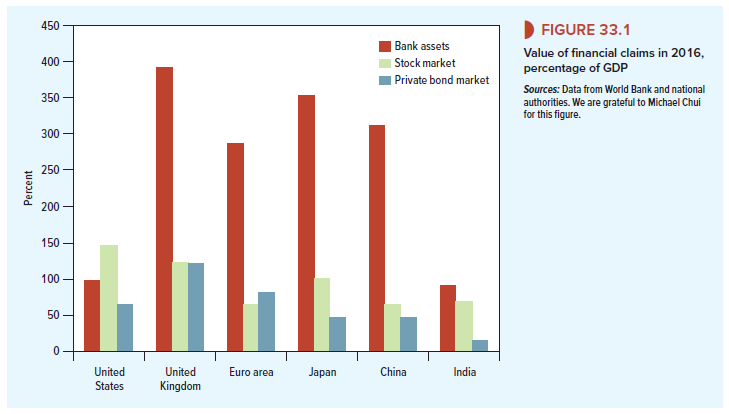

In most of this book, we have assumed that a large part of debt financing comes from public bond markets. Nothing in principle changes when a firm borrows from a bank instead. But in some countries, bond markets are stunted and bank financing is more important. Figure 33.1 shows the total values of bank loans, private (nongovernment) bonds, and stock markets in different parts of the world in 2016. To measure these financial claims on a comparable basis, the amounts are scaled by gross domestic product (GDP).

Company financing in the United States is different from that in most other countries. The United States not only has a large amount of bank loans outstanding, but there is also a large stock market and a large corporate bond market. Thus, the United States is said to have a market-based financial system. Stock market value is also high in the United Kingdom, but bank loans are much more important than the bond market. However, this is because the UK is an international banking center, so the bank loan figure includes eurocurrency loans. The figure does not represent just domestic loans. In Europe, Japan, and China, bank financing again outpaces bond markets, but the stock market is relatively small. In India, the financial system is less developed overall, with banks in particular being relatively small compared to most other countries. Most countries in Europe, including Germany, France, Italy, and Spain, have bank-based financial systems. So do many Asian countries, including Japan, China, and India.

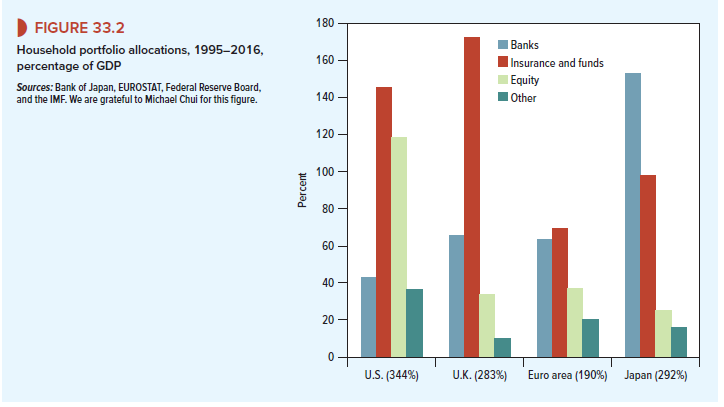

Let’s look at these regions from a different perspective. Figure 33.2 shows the financial investments made by households, again scaled by GDP.[2] (“Households” means individual investors.) Household portfolios are divided into four categories: bank deposits, insurance policies and mutual and pension funds, equity securities, and “other.” Notice the differences in the total amounts of financial assets in Figure 33.2. Summing the columns for each country and region, the amount of financial assets is 344% of GDP in the United States, 283% in the United Kingdom, 190% in Europe, and 292% in Japan. This does not mean that European investors are poor, just that they hold less wealth in the form of financial assets. Figure 33.2 excludes other important investment categories, such as real estate or privately owned businesses. It also excludes the value of pensions provided by governments.

In the United States, a large fraction of households’ portfolios is held directly in equity securities, mostly common stocks. Therefore, individual investors can potentially play an important role in corporate governance. Direct equity holdings are smallest in Japan. Japanese households could not play a significant direct role in corporate governance even if they wanted to. They can’t vote shares that they don’t own.

Where direct equity investment is small, household investments in bank deposits, insurance policies, and mutual and pension funds are correspondingly large. In the United Kingdom, the insurance and funds category dominates, with bank deposits in second place. In Europe, bank deposits and insurance and funds run a close race for first. In Japan, bank deposits win by a mile, with insurance and funds in second place and equities a distant third.

Figure 33.2 tells us that in many parts of the world, there are relatively few individual stockholders. Most individuals don’t invest directly in equity markets, but indirectly, through insurance companies, mutual funds, banks, and other financial intermediaries. Of course, the thread of ownership traces back through these intermediaries to individual investors. All assets are ultimately owned by individuals. There are no Martian or extraterrestrial investors that we know of.[3]

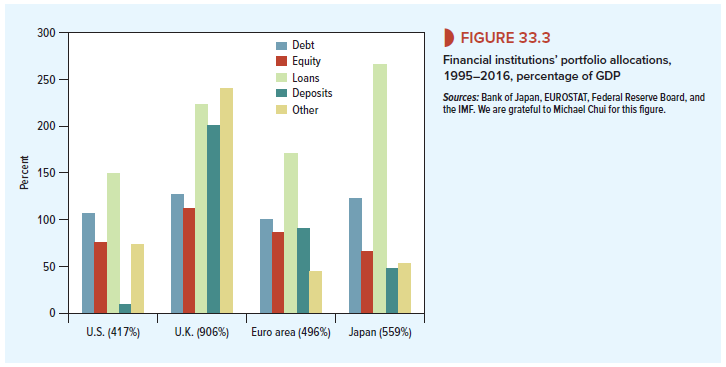

Now let’s look at financial institutions. Figure 33.3 shows the financial assets held by financial institutions, including banks, mutual funds, insurance companies, pension funds, and other intermediaries. These investments are smaller in the United States, relative to GDP, than in other countries (as expected in the U.S. market-based system). Financial institutions in the United Kingdom, Europe, and Japan have invested large sums in loans and in deposits. Holdings of equity are highest in the United Kingdom. These holdings are mainly owned by insurance companies and pension funds.

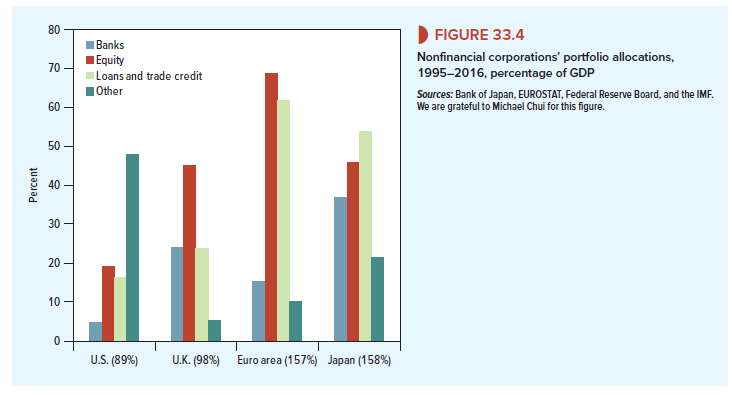

We’ve covered households and financial institutions. Is there any other source for corporate financing? Yes, financing can come from other corporations. Take a look at Figure 33.4, which shows the financial assets held by nonfinancial corporations. Perhaps the most striking feature is the large amount of equity held by firms in Europe. The amount of equity held in Japan and the United Kingdom is also large. In the United States it is relatively small. As we will see, these holdings of shares by other nonfinancial corporations have important implications for corporate ownership and governance.

Another interesting aspect of Figure 33.4 is the large amount of intercompany loans and trade credit in Europe and Japan. Many Japanese firms rely heavily on trade-credit financing— that is, on accounts payable to other firms. Of course, the other firms see the reverse side of trade credit: They are providing financing in the form of accounts receivable.

Figures 33.1 to 33.4 show that just drawing a line between market-based, “Anglo-Saxon” financial systems and bank-based financial systems is simplistic. We need to dig a little deeper when comparing financial systems. For example, more equity is held directly by households in the United States than in the United Kingdom, and the portfolio allocations of households, nonfinancial corporations, and financial institutions are also significantly different. In addition, we noted the large cross-holdings of shares among European corporations. Finally, Japanese households put significantly more of their savings in banks and Japanese corporations use trade credit much more than in other advanced economies.

Investor Protection and the Development of Financial Markets

What explains the importance of financial markets in some countries, while other countries rely less on markets and more on banks and other financial institutions? One answer is investor protection. Stock and bond markets thrive where investors in these markets are protected reasonably well.

Investors’ property rights are much better protected in some parts of the world than others. La Porta, Lopez-de-Silanes, Shleifer, Vishny, and others have developed quantitative measures of investor protection based on shareholders’ and creditors’ rights and the quality of law enforcement. Countries with poor scores generally have smaller stock markets, measured by aggregate market value relative to GDP, and the numbers of listed firms and initial public offerings are smaller relative to population. Poor scores also mean less debt financing for private firms.[4]

It’s easy to understand why poor protection of outside investors stunts the growth of financial markets. A more difficult question is why protection is good in some countries and poor in others. La Porta, Lopez-de-Silanes, Shleifer, and Vishny point to the origin of legal systems. They distinguish legal systems derived from the common-law tradition, which originated in England, from systems based on civil law, which evolved in France, Germany, and Scandinavia. The English, French, and German systems have spread around the world by conquest, imperialism, and imitation. Both shareholders and creditors, it is argued, are better protected by the law in countries that adopted the common-law tradition.

But Rajan and Zingales[5] point out that France, Belgium, and Germany, which are civil- law countries, had well-developed financial markets early in the twentieth century. Relative to GDP, these countries’ financial markets were then about the same size as markets in the United Kingdom and bigger than those in the United States. These rankings were reversed in the second half of the century after World War II, although financial markets are now expanding and playing a greater role in European economies. Rajan and Zingales believe that these reversals can be attributed to political trends and shifts in government policy. For example, they recount the backlash against financial markets after the stock market crash of 1929 and the expansion of government regulation and ownership in the Great Depression and after World War II.

It remains to be seen how political factors will fully play out in the wake of the financial crisis of 2007-2009 and the eurozone sovereign debt crisis that started in 2010. These have already had significant effects, which seem likely to continue.

I am constantly looking online for ideas that can help me. Thx!