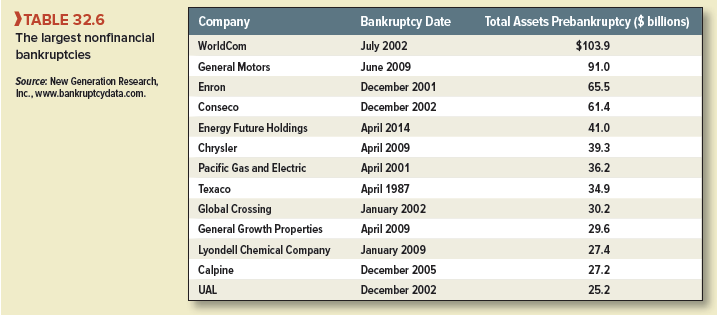

Some firms are forced to reorganize by the onset of financial distress. At this point they need to agree to a reorganization plan with their creditors or file for bankruptcy. We list the largest nonfinancial U.S. bankruptcies in Table 32.6. The credit crunch also ensured a good dollop of large financial bankruptcies. Lehman Brothers tops the list. It failed in September 2008 with assets of $691.1 billion. Two weeks later, Washington Mutual went the same way with assets of $327.9 billion.

Bankruptcy proceedings in the United States may be initiated by the creditors, but in the case of public corporations it is usually the firm itself that decides to file. It can choose one of two procedures, which are set out in Chapters 7 and 11 of the 1978 Bankruptcy Reform Act. The purpose of Chapter 7 is to oversee the firm’s death and dismemberment, while Chapter 11 seeks to nurse the firm back to health.

Most small firms make use of Chapter 7. In this case, the bankruptcy judge appoints a trustee, who then closes the firm down and auctions off the assets. The proceeds from the auction are used to pay off the creditors. Secured creditors can recover the value of their collateral. Whatever is left over goes to the unsecured creditors, who take assigned places in a queue. (Secured creditors join as unsecured to the extent that their collateral is not worth enough to repay the secured debt.) The court and the trustee are first in line. Wages come next, followed by federal and state taxes and debts to some government agencies such as the Pension Benefit Guarantee Corporation. The remaining unsecured creditors mop up any remaining crumbs from the table.[1] Frequently, the trustee needs to prevent some creditors from trying to jump the gun and collect on their debts, and sometimes the trustee retrieves property that a creditor has recently seized.

Managers of small firms that are in trouble know that Chapter 7 bankruptcy means the end of the road and, therefore, try to put off filing as long as possible. For this reason, Chapter 7 proceedings are often launched not by the firm, but by its creditors.

When large public companies can’t pay their debts, they generally attempt to rehabilitate the business. This is in the shareholders’ interests; they have nothing to lose if things deteriorate further and everything to gain if the firm recovers. The procedures for rehabilitation are set out in Chapter 11. Most companies find themselves in Chapter 11 because they can’t pay their debts. But sometimes companies have filed for Chapter 11 not because they run out of cash, but to deal with burdensome labor contracts or lawsuits. For example, Delphi, the automotive parts manufacturer, filed for bankruptcy in 2005. Delphi’s North American operations were running at a loss, partly because of high-cost labor contracts with the United Auto Workers (UAW) and partly because of the terms of its supply contract with GM, its largest customer. Delphi sought the protection of Chapter 11 to restructure its operations and to negotiate better terms with the UAW and GM.

The aim of Chapter 11 is to keep the firm alive and operating while a plan of reorganization is worked out.[2] During this period, other proceedings against the firm are halted, and the company usually continues to be run by its existing management.[3] The responsibility for developing the plan falls on the debtor firm but, if it cannot devise an acceptable plan, the court may invite anyone to do so—for example, a committee of creditors.

The plan goes into effect if it is accepted by the creditors and confirmed by the court. Each class of creditors votes separately on the plan. Acceptance requires approval by at least one-half of votes cast in each class, and those voting “aye” must represent two-thirds of the value of the creditors’ aggregate claim against the firm. The plan also needs to be approved by two-thirds of the shareholders. Once the creditors and the shareholders have accepted the plan, the court normally approves it, provided that each class of creditors is in favor and that the creditors will be no worse off under the plan than they would be if the firm’s assets were liquidated and the proceeds distributed. Under certain conditions the court may confirm a plan even if one or more classes of creditors votes against it,[4] but the rules for a “cramdown” are complicated, and we will not attempt to cover them here.

The reorganization plan is basically a statement of who gets what; each class of creditors gives up its claim in exchange for new securities or a mixture of new securities and cash. The problem is to design a new capital structure for the firm that will (1) satisfy the creditors and (2) allow the firm to solve the business problems that got the firm into trouble in the first place.[5] Sometimes satisfying these two conditions requires a plan of baroque complexity, involving the creation of a dozen or more new securities.

The Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC) plays a role in many reorganizations, particularly for large, public companies. Its interest is to ensure that all relevant and material information is disclosed to the creditors before they vote on the proposed plan of reorganization.

Chapter 11 proceedings are often successful, and the patient emerges fit and healthy. But in other cases, rehabilitation proves impossible, and the assets are liquidated under Chapter 7. Sometimes the firm may emerge from Chapter 11 for a brief period before it is once again submerged by disaster and back in the bankruptcy court. For example, the venerable airline TWA came out of Chapter 11 bankruptcy at the end of 1993, was back again less than two years later, and then for a third time in 2001, prompting jokes about “Chapter 22” and “Chapter 33.”[6]

1. Is Chapter 11 Efficient?

Here is a simple view of the bankruptcy decision: Whenever a payment is due to creditors, management checks the value of the equity. If the value is positive, the firm makes the payment (if necessary, raising the cash by an issue of shares). If the equity is valueless, the firm defaults on its debt and files for bankruptcy. If the assets of the bankrupt firm can be put to better use elsewhere, the firm is liquidated and the proceeds are used to pay off the creditors; otherwise, the creditors become the new owners and the firm continues to operate.[7]

In practice, matters are rarely so simple. For example, we observe that firms often petition for bankruptcy even when the equity has a positive value. And firms often continue to operate even when the assets could be used more efficiently elsewhere. The problems in Chapter 11 usually arise because the goal of paying off the creditors conflicts with the goal of maintaining the business as a going concern. We described in Chapter 18 how the assets of Eastern Airlines seeped away in bankruptcy. When the company filed for Chapter 11, its assets were more than sufficient to repay in full its liabilities of $3.7 billion. But the bankruptcy judge was determined to keep Eastern flying. When it finally became clear that Eastern was a terminal case, the assets were sold off and the creditors received less than $900 million. The creditors would clearly have been better off if Eastern had been liquidated immediately; the unsuccessful attempt at resuscitation cost the creditors $2.8 billion.[8]

Here are some further reasons that Chapter 11 proceedings do not always achieve an efficient solution:

- Although the reorganized firm is legally a new entity, it is entitled to the tax-loss carryforwards belonging to the old firm. If the firm is liquidated rather than reorganized, the tax-loss carry-forwards disappear. Thus, there is a tax incentive to continue operating the firm even when its assets could be sold and put to better use elsewhere.

- If the firm’s assets are sold, it is easy to determine what is available to pay creditors. However, when the company is reorganized, it needs to conserve cash. Therefore, claimants are often paid off with a mixture of cash and securities. This makes it less easy to judge whether they receive a fair shake.

- Senior creditors, who know they are likely to get a raw deal in a reorganization, may press for a liquidation. Shareholders and junior creditors prefer a reorganization. They hope that the court will not interpret the creditors’ pecking order too strictly and that they will receive consolation prizes when the firm’s remaining value is sliced up.

- Although shareholders and junior creditors are at the bottom of the pecking order, they have a secret weapon—they can play for time. When they use delaying tactics, the junior creditors are betting on a stroke of luck that will rescue their investment. On the other hand, the senior claimants know that time is working against them, so they may be prepared to settle for a lower payoff as part of the price for getting the plan accepted. Also, prolonged bankruptcy cases are costly, as we pointed out in Chapter 18. Senior claimants may see their money seeping into lawyers’ pockets and decide to settle quickly.

But bankruptcy practices do change, and in recent years, Chapter 11 proceedings have become more creditor-friendly.[9] For example, equity investors and junior debtholders used to find that managers were willing allies in dragging out a settlement, but these days, the managers of bankrupt firms often receive a key-employee retention plan, which provides them with a large bonus if the reorganization proceeds quickly and a smaller one if the company lingers on in Chapter 11. For large public bankruptcies, this has contributed to a reduction in the time spent in bankruptcy from about 840 days in 2007 to 430 in 2017.[10]

While a reorganization plan is being drawn up, the company is likely to need additional working capital. It has, therefore, become increasingly common to allow the firm to buy goods on credit and to borrow money (known as debtor in possession, or DIP, debt). The lenders, who frequently comprise the firm’s existing creditors, receive senior claims and can insist on stringent conditions. DIP lenders therefore have considerable influence on the outcome of the bankruptcy proceedings.

As creditors have gained more influence, shareholders of the bankrupt firms have received fewer and fewer crumbs. In recent years, the court has faithfully observed the pecking order in about 90% of Chapter 11 settlements.

In 2009, GM and Chrysler both filed for bankruptcy. They were not only two of the largest bankruptcies ever, but they were also extraordinary legal events. With the help of billions of fresh money from the U.S. Treasury, the companies were in and out of bankruptcy court with blinding speed, compared with the normal placid pace of Chapter 11. The U.S. government was deeply involved in the rescue and the financing of New GM and New Chrysler. The nearby box explains some of the financial issues raised by the Chrysler bankruptcy. The GM bankruptcy raised similar issues.

2. Workouts

If Chapter 11 reorganizations are not efficient, why don’t firms bypass the bankruptcy courts and get together with their creditors to work out a solution? Many firms that are in distress do first seek a negotiated settlement, or workout. For example, they can seek to delay payment of the debt or negotiate an interest rate holiday. However, shareholders and junior creditors know that senior creditors are anxious to avoid formal bankruptcy proceedings. So they are likely to be tough negotiators, and senior creditors generally need to make concessions to reach agree- ment.[11] The larger the firm, and the more complicated its capital structure, the less likely it is that everyone will agree to any proposal.

Sometimes the firm does agree to an informal workout with its creditors and then files under Chapter 11 to obtain the approval of the bankruptcy court. Such prepackaged or prenegotiated bankruptcies reduce the likelihood of subsequent litigation and allow the firm to gain the special tax advantages of Chapter 11.[12] For example, in 2014 Energy Future Holdings, the electric utility company, arranged a prepack after reaching agreement with its creditors. Since 1980, about 30% of U.S. bankruptcies have been prepackaged or prenegotiated.[13]

3. Alternative Bankruptcy Procedures

The U.S. bankruptcy system is often described as a debtor-friendly system. Its principal focus is on rescuing firms in distress. But this comes at a cost because there are many instances in which the firm’s assets would be better deployed in other uses. Michael Jensen, a critic of Chapter 11, has argued that “the U.S. bankruptcy code is fundamentally flawed. It is expensive, it exacerbates conflicts of interest among different classes of creditors, and it often takes years to resolve individual cases.” Jensen’s proposed solution is to require that any bankrupt company be put immediately on the auction block and the proceeds distributed to claimants in accordance with the priority of their claims.[14]

In some countries, the bankruptcy system is even more friendly to debtors. For example, in France the primary duties of the bankruptcy court are to keep the firm in business and preserve employment. Only once these duties have been performed does the court have a responsibility to creditors. Creditors have minimal control over the process, and it is the court that decides whether the firm should be liquidated or preserved. If the court chooses liquidation, it may select a bidder who offers a lower price but better prospects for employment.

The UK is at the other end of the scale. When a British firm is unable to pay its debts, the control rights pass to the creditors. Most commonly, a designated secured creditor appoints a receiver, who assumes direction of the firm, sells sufficient assets to repay the secured creditors, and ensures that any excess funds are used to pay off the other creditors according to the priority of their claims.

Davydenko and Franks, who have examined alternative bankruptcy systems, found that banks responded to these differences in the bankruptcy code by adjusting their lending practices. Nevertheless, as you would expect, lenders recover a smaller proportion of their money in those countries that have a debtor-friendly bankruptcy system. For example, in France the banks recover on average only 47% of the money owed by bankrupt firms, while in the UK, the corresponding figure is 69%.[15]

Of course, the grass is always greener elsewhere. In the United States and France, critics complain about the costs of trying to save businesses that are no longer viable. By contrast, in countries such as the UK, bankruptcy laws are blamed for the demise of healthy businesses and Chapter 11 is held up as a model of an efficient bankruptcy system.

An interesting discussion is worth comment. I think that you should write more on this topic, it might not be a taboo subject but generally people are not enough to speak on such topics. To the next. Cheers