We have seen how market interest rates are used to help make capital investment and intertemporal production decisions. But what determines interest rate levels? Why do they fluctuate over time? To answer these questions, remember that an interest rate is the price that borrowers pay lenders to use their funds. Like any market price, interest rates are determined by supply and demand—in this case, the supply and demand for loanable funds.

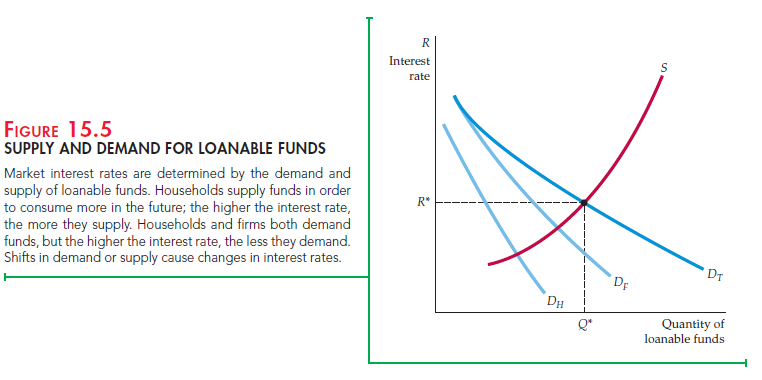

The supply of loanable funds comes from households that wish to save part of their incomes in order to consume more in the future (or make bequests to their heirs). For example, some households have high incomes now but expect to earn less after retirement. Saving lets them spread their consumption more evenly over time. In addition, because they receive interest on the money they lend, they can consume more in the future in return for consuming less now. As a result, the higher the interest rate, the greater the incentive to save. The supply of loanable funds is therefore an upward-sloping curve, labeled S in Figure 15.5.

The demand for loanable funds has two components. First, some households want to consume more than their current incomes, either because their incomes are low now but are expected to grow, or because they want to make a large purchase (e.g., a house) that must be paid for out of future income. These households are willing to pay interest in return for not having to wait to consume. However, the higher the interest rate, the greater the cost of consuming rather than waiting, so the less willing these households will be to borrow. The household demand for loanable funds is therefore a declining function of the interest rate. In Figure 15.5, it is the curve labeled DH.

The second source of demand for loanable funds is firms that want to make capital investments. Remember that firms will invest in projects with NPVs that are positive because a positive NPV means that the expected return on the project exceeds the opportunity cost of funds. That opportunity cost—the discount rate used to calculate the NPV—is the interest rate, perhaps adjusted for risk. Often firms borrow to invest because the flow of profits from an investment comes in the future while the cost of an investment must usually be paid now. The desire of firms to invest is thus an important source of demand for loanable funds.

As we saw earlier, however, the higher the interest rate, the lower the NPV of a project. If interest rates rise, some investment projects that had positive NPVs will now have negative NPVs and will therefore be cancelled. Overall, because firms’ willingness to invest falls when interest rates rise, their demand for loanable funds also falls. The demand for loanable funds by firms is thus a downward-sloping curve; in Figure 15.5, it is labeled DF.

The total demand for loanable funds is the sum of household demand and firm demand; in Figure 15.5, it is the curve DT. This total demand curve, together with the supply curve, determines the equilibrium interest rate. In Figure 15.5, that rate is R*.

Figure 15.5 can also help us understand why interest rates change. Suppose the economy goes into a recession. Firms will expect lower sales and lower future profits from new capital investments. The NPVs of projects will fall, and firms’ willingness to invest will decline, as will their demand for loanable funds. DF, and therefore DT, will shift to the left, and the equilibrium interest rate will fall. Or suppose the federal government spends much more money than it collects through taxes—i.e., that it runs a large deficit. It will have to borrow to finance the deficit, shifting the total demand for loanable funds DT to the right, so that R increases. The monetary policies of the Federal Reserve are another important determinant of interest rates. The Federal Reserve can create money, shifting the supply of loanable funds to the right and reducing R.

A Variety of Interest Rates

Figure 15.5 aggregates individual demands and supplies as though there were a single market interest rate. In fact, households, firms, and the government lend and borrow under a variety of terms and conditions. As a result, there is a wide range of “market” interest rates. Here we briefly describe some of the more important rates that are quoted in the newspapers and sometimes used for capital investment decisions.

- Treasury Bill Rate A Treasury bill is a short-term (one year or less) bond issued by the U.S. government. It is a pure discount bond—i.e., it makes no coupon payments but instead is sold at a price less than its redemption value at maturity. For example, a three-month Treasury bill might be sold for $98. In three months, it can be redeemed for $100; it thus has an effective three-month yield of about 2 percent and an effective annual yield of about 8 percent.[1] The Treasury bill rate can be viewed as a short-term, risk-free rate.

- Treasury Bond Rate A Treasury bond is a longer-term bond issued by the U.S. government for more than one year and typically for 10 to 30 years. Rates vary, depending on the maturity of the bond.

- Discount Rate Commercial banks sometimes borrow for short periods from the Federal Reserve. These loans are called discounts, and the rate that the Federal Reserve charges on them is the discount rate.

- Federal Funds Rate This is the interest rate that banks charge one another for overnight loans of federal funds. Federal funds consist of currency in circulation plus deposits held at Federal Reserve banks. Banks keep funds at Federal Reserve banks in order to meet reserve requirements. Banks with excess reserves may lend these funds to banks with reserve deficiencies at the federal funds rate. The federal funds rate is a key instrument of monetary policy used by the Federal Reserve.

- Commercial Paper Rate Commercial paper refers to short-term (six months or less) discount bonds issued by high-quality corporate borrowers. Because commercial paper is only slightly riskier than Treasury bills, the commercial paper rate is usually less than 1 percent higher than the Treasury bill rate.

- Prime Rate This is the rate (sometimes called the reference rate) that large banks post as a reference point for short-term loans to their biggest corporate borrowers. As we saw in Example 12.4 (page 475), this rate does not fluctuate from day to day as other rates do.

- Corporate Bond Rate Newspapers and government publications report the average annual yields on long-term (typically 20-year) corporate bonds in different risk categories (e.g., high-grade, medium-grade, etc.). These average yields indicate how much corporations are paying for long-term debt. However, as we saw in Example 15.2, the yields on corporate bonds can vary considerably, depending on the financial strength of the corporation and the time to maturity for the bond.

Source: Pindyck Robert, Rubinfeld Daniel (2012), Microeconomics, Pearson, 8th edition.

Great write-up, I¦m regular visitor of one¦s web site, maintain up the nice operate, and It is going to be a regular visitor for a long time.

I got good info from your blog