Two other closely related forms of price discrimination are important and widely practiced. The first of these is intertemporal price discrimination: sep- arating consumers with different demand functions into different groups by charging different prices at different points in time. The second is peak-load pricing: charging higher prices during peak periods when capacity constraints cause marginal costs to be high. Both of these strategies involve charging differ- ent prices at different times, but the reasons for doing so are somewhat different in each case. We will take each in turn.

1. Intertemporal Price Discrimination

The objective of intertemporal price discrimination is to divide consumers into high-demand and low-demand groups by charging a price that is high at first but falls later. To see how this strategy works, think about how an electronics company might price new, technologically advanced equipment, such as high- performance digital cameras or LCD television monitors. In Figure 11.7, D1 is the (inelastic) demand curve for a small group of consumers who value the product highly and do not want to wait to buy it (e.g., photography buffs who want the latest camera). D2 is the demand curve for the broader group of consumers who are more willing to forgo the product if the price is too high. The strategy, then, is to offer the product initially at the high price P1, selling mostly to consumers on demand curve D1. Later, after this first group of consumers has bought the product, the price is lowered to P2, and sales are made to the larger group of consumers on demand curve D .9

There are other examples of intertemporal price discrimination. One involves charging a high price for a first-run movie and then lowering the price after the movie has been out a year. Another, practiced almost universally by publish- ers, is to charge a high price for the hardcover edition of a book and then to release the paperback version at a much lower price about a year later. Many people think that the lower price of the paperback is due to a much lower cost of production, but this is not true. Once a book has been edited and typeset, the marginal cost of printing an additional copy, whether hardcover or paperback, is quite low, perhaps a dollar or so. The paperback version is sold for much less not because it is much cheaper to print but because high-demand consumers have already purchased the hardbound edition. The remaining consumers— paperback buyers—generally have more elastic demands.

2. Peak–Load Pricing

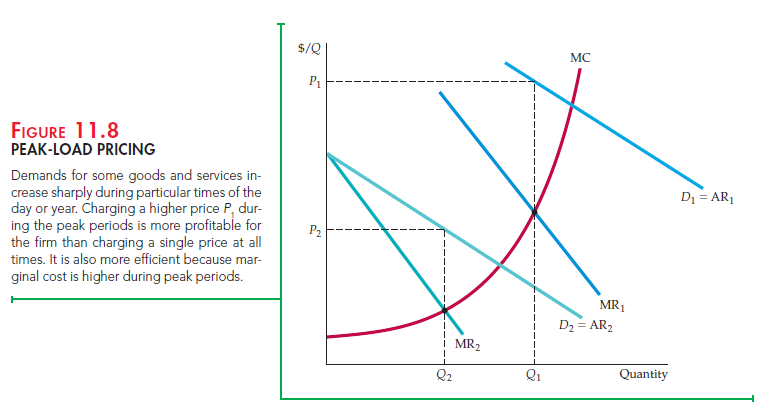

Peak-load pricing also involves charging different prices at different points in time. Rather than capturing consumer surplus, however, the objective is to increase eco- nomic efficiency by charging consumers prices that are close to marginal cost.

For some goods and services, demand peaks at particular times—for roads and tunnels during commuter rush hours, for electricity during late summer afternoons, and for ski resorts and amusement parks on weekends. Marginal cost is also high during these peak periods because of capacity constraints. Prices should thus be higher during peak periods.

This is illustrated in Figure 11.8, where D1 is the demand curve for the peak period and D2 the demand curve for the nonpeak period. The firm sets marginal revenue equal to marginal cost for each period, obtaining the high price P1 for the peak period and the lower price P2 for the nonpeak period, selling corresponding quantities Q1 and Q2. This strategy increases the firm’s profit above what it would be if it charged one price for all periods. It is also more efficient: The sum of pro-ducer and consumer surplus is greater because prices are closer to marginal cost.

The efficiency gain from peak-load pricing is important. If the firm were a regulated monopolist (e.g., an electric utility), the regulatory agency should set the prices P1 and P2 at the points where the demand curves, D1 and D2, intersect the marginal cost curve, rather than where the marginal revenue curves inter- sect marginal cost. In that case, consumers realize the entire efficiency gain.

Note that peak-load pricing is different from third-degree price discrimina- tion. With third-degree price discrimination, marginal revenue must be equal for each group of consumers and equal to marginal cost. Why? Because the costs of serving the different groups are not independent. For example, with unrestricted versus discounted air fares, increasing the number of seats sold at discounted fares affects the cost of selling unrestricted tickets—marginal cost rises rapidly as the airplane fills up. But this is not so with peak-load pricing (or for that matter, with most instances of intertemporal price discrimination). Selling more tickets for ski lifts or amusement parks on a weekday does not significantly raise the cost of selling tickets on the weekend. Similarly, selling more electricity during off- peak periods will not significantly increase the cost of selling electricity during peak periods. As a result, price and sales in each period can be determined inde- pendently by setting marginal cost equal to marginal revenue for each period.

Movie theaters, which charge more for evening shows than for matinees, are another example. For most movie theaters, the marginal cost of serving customers during the matinee is independent of marginal cost during the evening. The owner of a movie theater can determine the optimal prices for the evening and matinee shows independently, using estimates of demand and marginal cost in each period.

Source: Pindyck Robert, Rubinfeld Daniel (2012), Microeconomics, Pearson, 8th edition.

Woh I love your content, saved to favorites! .

Hello.This post was extremely fascinating, especially since I was investigating for thoughts on this issue last Thursday.