Production decisions often have intertemporal aspects—production today affects sales or costs in the future. The learning curve, which we discussed in Chapter 7, is an example of this. By producing today, the firm gains experience that lowers future costs. In this case, production today is partly an investment in future cost reduction, and the value of this investment must be taken into account when comparing costs and benefits. Another example is the production of a deplet- able resource. When the owner of an oil well pumps oil today, less oil is available for future production. This must be taken into account when deciding how much to produce.

Production decisions in cases like these involve comparisons between costs and benefits today with costs and benefits in the future. We can make those comparisons using the concept of present discounted value. We’ll look in detail at the case of a depletable resource, although the same principles apply to other intertemporal production decisions.

1. The Production Decision of an Individual Resource Producer

Suppose your rich uncle gives you an oil well. The well contains 1000 barrels of oil that can be produced at a constant average and marginal cost of $10 per barrel. Should you produce all the oil today, or should you save it for the future?

You might think that the answer depends on the profit you can earn if you remove the oil from the ground. After all, why not remove the oil if its price is greater than the cost of extraction? However, this ignores the opportunity cost of using up the oil today so that it is not available for the future.

The correct answer, then, depends not on the current profit level but on how fast you expect the price of oil to rise. Oil in the ground is like money in the bank: You should keep it in the ground only if it earns a return at least as high as the market interest rate. If you expect the price of oil to remain constant or rise very slowly, you would be better off extracting and selling all of it now and investing the proceeds. But if you expect the price of oil to rise rapidly, you should leave it in the ground.

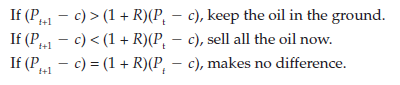

How fast must the price rise for you to keep the oil in the ground? The value of each barrel of oil in your well is equal to the price of oil less the $10 cost of extracting it. (This is the profit you can obtain by extracting and selling each barrel.) This value must rise at least as fast as the rate of interest for you to keep the oil. Your production decision rule is therefore: Keep all your oil if you expect its price less its extraction cost to rise faster than the rate of interest. Extract and sell all of it if you expect price less cost to rise at less than the rate of interest. What if you expect price less cost to rise at exactly the rate of interest? Then you would be indifferent between extracting the oil and leaving it in the ground. Letting Pt be the price of oil this year, Pt+1 the price next year, and c the cost of extraction, we can write this production rule as follows:

Given our expectation about the growth rate of oil prices, we can use this rule to determine production. But how fast should we expect the market price of oil to rise?

2. The Behavior of Market Price

Suppose there were no OPEC cartel and the oil market consisted of many competitive producers with oil wells like our own. We could then determine how quickly oil prices are likely to rise by considering the production decisions of other producers. If other producers want to earn the highest possible return, they will follow the production rule we stated above. This means that price less marginal cost must rise at exactly the rate of interest.20 To see why, suppose price less cost were to rise faster than the rate of interest. In that case, no one would sell any oil. Inevitably, this would drive up the current price. If, on the other hand, price less cost were to rise at a rate less than the rate of interest, everyone would try to sell all of their oil immediately, which would drive the current price down.

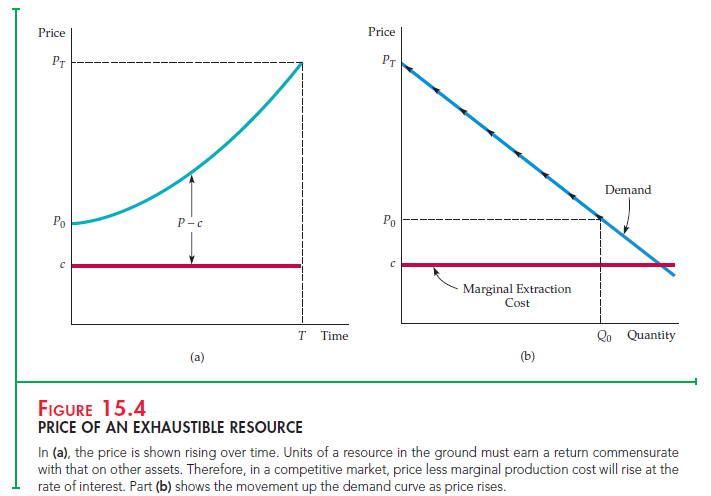

Figure 15.4 illustrates how the market price must rise. The marginal cost of extraction is c, and the price and total quantity produced are initially P0 and Q0. Part (a) shows the net price, P – c, rising at the rate of interest. Part (b) shows that as price rises, the quantity demanded falls. This continues until time T, when all the oil has been used up and the price PT is such that demand is just zero.

3. User Cost

We saw in Chapter 8 that a competitive firm always produces up to the point at which price is equal to marginal cost. However, in a competitive market for an exhaustible resource, price exceeds marginal cost (and the difference between price and marginal cost rises over time). Does this conflict with what we learned in Chapter 8?

No, once we recognize that the total marginal cost of producing an exhaustible resource is greater than the marginal cost of extracting it from the ground. There is an additional opportunity cost because producing and selling a unit today makes it unavailable for production and sale in the future. We call this opportunity cost the user cost of production. In Figure 15.4, user cost is the difference between price and marginal production cost. It rises over time because as the resource remaining in the ground becomes scarcer, the opportunity cost of depleting another unit becomes higher.

4. Resource Production by a Monopolist

What if the resource is produced by a monopolist rather than by a competitive industry? Should price less marginal cost still rise at the rate of interest?

Suppose a monopolist is deciding between keeping an incremental unit of a resource in the ground, or producing and selling it. The value of that unit is the marginal revenue less the marginal cost. The unit should be left in the ground if its value is expected to rise faster than the rate of interest; it should be produced and sold if its value is expected to rise at less than the rate of interest. Since the monopolist controls total output, it will produce so that marginal revenue less marginal cost—i.e., the value of an incremental unit of resource—rises at exactly the rate of interest:

![]()

Note that this rule also holds for a competitive firm. For a competitive firm, however, marginal revenue equals the market price p.

For a monopolist facing a downward-sloping demand curve, price is greater than marginal revenue. Therefore, if marginal revenue less marginal cost rises at the rate of interest, price less marginal cost will rise at less than the rate of interest. We thus have the interesting result that a monopolist is more conservationist than a competitive industry. In exercising monopoly power, the monopolist starts out charging a higher price and depletes the resource more slowly.

Source: Pindyck Robert, Rubinfeld Daniel (2012), Microeconomics, Pearson, 8th edition.

Quаlitʏ articles is the main to be a focus for the

people to paү a visit the web site, that’s what

this web page is pгoviԁing.

Thanks for your personal marvelous posting! I genuinely enjoyed reading it, you could be a great author.I will be sure to bookmark your blog and will eventually come back down the road. I want to encourage that you continue your great work, have a nice holiday weekend!

Great post. I am facing a couple of these problems.