What is Action Research?

Definition

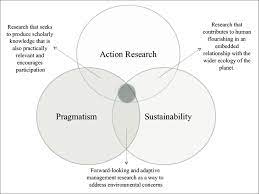

Action research is known by many other names, including participatory research, collaborative inquiry, emancipatory research, action learning, and contextual action research, but all are variations on a theme. Put simply, action research is “learning by doing” – a group of people identify a problem, do something to resolve it, see how successful their efforts were, and if not satisfied, try again. While this is the essence of the approach, there are other key attributes of action research that differentiate it from common problem-solving activities that we all engage in every day. A more succinct definition is,

“Action research…aims to contribute both to the practical concerns of people in an immediate problematic situation and to further the goals of social science simultaneously. Thus, there is a dual commitment in action research to study a system and concurrently to collaborate with members of the system in changing it in what is together regarded as a desirable direction. Accomplishing this twin goal requires the active collaboration of researcher and client, and thus it stresses the importance of co-learning as a primary aspect of the research process.”

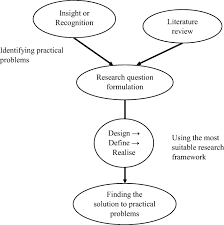

What separates this type of research from general professional practices, consulting, or daily problem-solving is the emphasis on scientific study, which is to say the researcher studies the problem systematically and ensures the intervention is informed by theoretical considerations. Much of the researcher’s time is spent on refining the methodological tools to suit the exigencies of the situation, and on collecting, analyzing, and presenting data on an ongoing, cyclical basis.

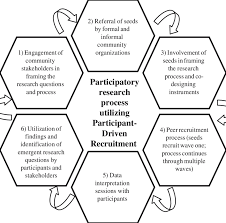

Several attributes separate action research from other types of research. Primary is its focus on turning the people involved into researchers, too – people learn best, and more willingly apply what they have learned, when they do it themselves. It also has a social dimension – the research takes place in real-world situations, and aims to solve real problems. Finally, the initiating researcher, unlike in other disciplines, makes no attempt to remain objective, but openly acknowledges their bias to the other participants.

The Action Research Process

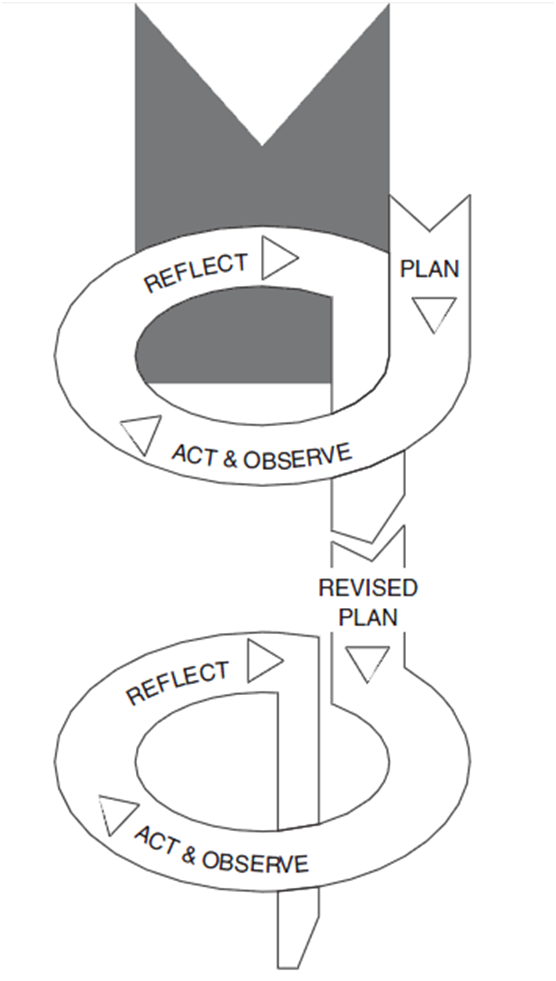

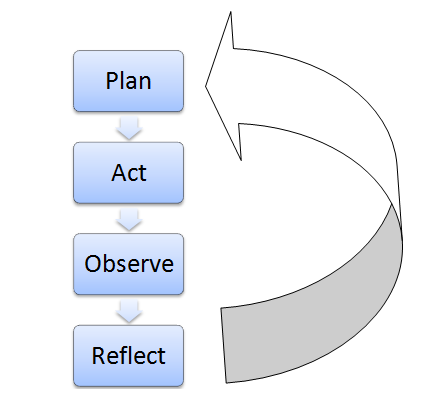

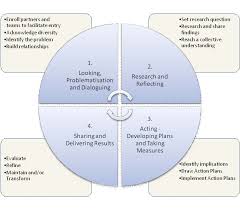

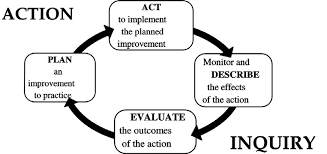

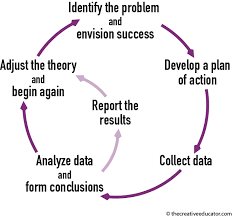

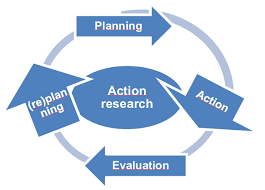

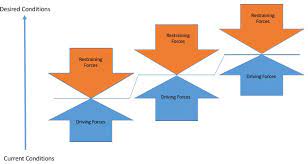

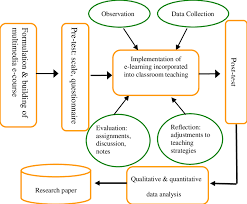

Stephen Kemmis has developed a simple model of the cyclical nature of the typical action research process (Figure 1). Each cycle has four steps: plan, act, observe, reflect.

Figure 1 Simple Action Research Model

(from MacIsaac, 1995)

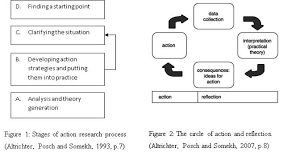

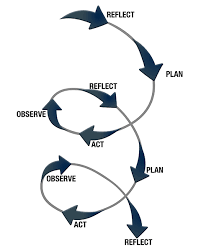

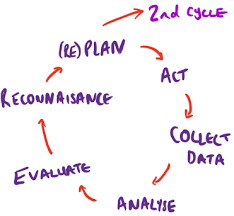

Gerald Susman (1983) gives a somewhat more elaborate listing. He distinguishes five phases to be conducted within each research cycle (Figure 2). Initially, a problem is identified and data is collected for a more detailed diagnosis. This is followed by a collective postulation of several possible solutions, from which a single plan of action emerges and is implemented. Data on the results of the intervention are collected and analyzed, and the findings are interpreted in light of how successful the action has been. At this point, the problem is re-assessed and the process begins another cycle. This process continues until the problem is resolved.

Figure 2 Detailed Action Research Model

(adapted from Susman 1983)

Principles of Action Research

What gives action research its unique flavour is the set of principles that guide the research. Winter (1989) provides a comprehensive overview of six key principles.

1) Reflexive critique

An account of a situation, such as notes, transcripts or official documents, will make implicit claims to be authoritative, i.e., it implies that it is factual and true. Truth in a social setting, however, is relative to the teller. The principle of reflective critique ensures people reflect on issues and processes and make explicit the interpretations, biases, assumptions and concerns upon which judgments are made. In this way, practical accounts can give rise to theoretical considerations.

2) Dialectical critique

Reality, particularly social reality, is consensually validated, which is to say it is shared through language. Phenomena are conceptualized in dialogue, therefore a dialectical critique is required to understand the set of relationships both between the phenomenon and its context, and between the elements constituting the phenomenon. The key elements to focus attention on are those constituent elements that are unstable, or in opposition to one another. These are the ones that are most likely to create changes.

3) Collaborative Resource

Participants in an action research project are co-researchers. The principle of collaborative resource presupposes that each person’s ideas are equally significant as potential resources for creating interpretive categories of analysis, negotiated among the participants. It strives to avoid the skewing of credibility stemming from the prior status of an idea-holder. It especially makes possible the insights gleaned from noting the contradictions both between many viewpoints and within a single viewpoint

4) Risk

The change process potentially threatens all previously established ways of doing things, thus creating psychic fears among the practitioners. One of the more prominent fears comes from the risk to ego stemming from open discussion of one’s interpretations, ideas, and judgments. Initiators of action research will use this principle to allay others’ fears and invite participation by pointing out that they, too, will be subject to the same process, and that whatever the outcome, learning will take place.

5) Plural Structure

The nature of the research embodies a multiplicity of views, commentaries and critiques, leading to multiple possible actions and interpretations. This plural structure of inquiry requires a plural text for reporting. This means that there will be many accounts made explicit, with commentaries on their contradictions, and a range of options for action presented. A report, therefore, acts as a support for ongoing discussion among collaborators, rather than a final conclusion of fact.

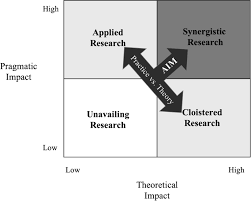

6) Theory, Practice, Transformation

For action researchers, theory informs practice, practice refines theory, in a continuous transformation. In any setting, people’s actions are based on implicitly held assumptions, theories and hypotheses, and with every observed result, theoretical knowledge is enhanced. The two are intertwined aspects of a single change process. It is up to the researchers to make explicit the theoretical justifications for the actions, and to question the bases of those justifications. The ensuing practical applications that follow are subjected to further analysis, in a transformative cycle that continuously alternates emphasis between theory and practice.

When is Action Research used?

Action research is used in real situations, rather than in contrived, experimental studies, since its primary focus is on solving real problems. It can, however, be used by social scientists for preliminary or pilot research, especially when the situation is too ambiguous to frame a precise research question. Mostly, though, in accordance with its principles, it is chosen when circumstances require flexibility, the involvement of the people in the research, or change must take place quickly or holistically.

It is often the case that those who apply this approach are practitioners who wish to improve understanding of their practice, social change activists trying to mount an action campaign, or, more likely, academics who have been invited into an organization (or other domain) by decision-makers aware of a problem requiring action research, but lacking the requisite methodological knowledge to deal with it.

Situating Action Research in a Research Paradigm

Positivist Paradigm

The main research paradigm for the past several centuries has been that of Logical Positivism. This paradigm is based on a number of principles, including: a belief in an objective reality, knowledge of which is only gained from sense data that can be directly experienced and verified between independent observers. Phenomena are subject to natural laws that humans discover in a logical manner through empirical testing, using inductive and deductive hypotheses derived from a body of scientific theory. Its methods rely heavily on quantitative measures, with relationships among variables commonly shown by mathematical means. Positivism, used in scientific and applied research, has been considered by many to be the antithesis of the principles of action research (Susman and Evered 1978, Winter 1989).

Interpretive Paradigm

Over the last half century, a new research paradigm has emerged in the social sciences to break out of the constraints imposed by positivism. With its emphasis on the relationship between socially-engendered concept formation and language, it can be referred to as the Interpretive paradigm. Containing such qualitative methodological approaches as phenomenology, ethnography, and hermeneutics, it is characterized by a belief in a socially constructed, subjectively-based reality, one that is influenced by culture and history. Nonetheless it still retains the ideals of researcher objectivity, and researcher as passive collector and expert interpreter of data.

Paradigm of Praxis

Though sharing a number of perspectives with the interpretive paradigm, and making considerable use of its related qualitative methodologies, there are some researchers who feel that neither it nor the positivist paradigms are sufficient epistemological structures under which to place action research (Lather 1986, Morley 1991). Rather, a paradigm of Praxis is seen as where the main affinities lie. Praxis, a term used by Aristotle, is the art of acting upon the conditions one faces in order to change them. It deals with the disciplines and activities predominant in the ethical and political lives of people. Aristotle contrasted this with Theoria – those sciences and activities that are concerned with knowing for its own sake. Both are equally needed he thought. That knowledge is derived from practice, and practice informed by knowledge, in an ongoing process, is a cornerstone of action research. Action researchers also reject the notion of researcher neutrality, understanding that the most active researcher is often one who has most at stake in resolving a problematic situation.

Evolution of Action Research

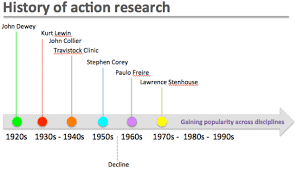

Origins in late 1940s

Kurt Lewin is generally considered the ‘father’ of action research. A German social and experimental psychologist, and one of the founders of the Gestalt school, he was concerned with social problems, and focused on participative group processes for addressing conflict, crises, and change, generally within organizations. Initially, he was associated with the Center for Group Dynamics at MIT in Boston, but soon went on to establish his own National Training Laboratories.

Lewin first coined the term ‘action research’ in his 1946 paper “Action Research and Minority Problems”,[v] characterizing Action Research as “a comparative research on the conditions and effects of various forms of social action and research leading to social action”, using a process of “a spiral of steps, each of which is composed of a circle of planning, action, and fact-finding about the result of the action”.

Eric Trist, another major contributor to the field from that immediate post-war era, was a social psychiatrist whose group at the Tavistock Institute of Human Relations in London engaged in applied social research, initially for the civil repatriation of German prisoners of war. He and his colleagues tended to focus more on large-scale, multi-organizational problems.

Both Lewin and Trist applied their research to systemic change in and between organizations. They emphasized direct professional – client collaboration and affirmed the role of group relations as basis for problem-solving. Both were avid proponents of the principle that decisions are best implemented by those who help make them.

Current Types of Action Research

By the mid-1970s, the field had evolved, revealing 4 main ‘streams’ that had emerged: traditional, contextural (action learning), radical, and educational action research.

Traditional Action Research

Traditional Action Research stemmed from Lewin’s work within organizations and encompasses the concepts and practices of Field Theory, Group Dynamics, T-Groups, and the Clinical Model. The growing importance of labour-management relations led to the application of action research in the areas of Organization Development, Quality of Working Life (QWL), Socio-technical systems (e.g., Information Systems), and Organizational Democracy. This traditional approach tends toward the conservative, generally maintaining the status quo with regards to organizational power structures.

Contextural Action Research (Action Learning)

Contextural Action Research, also sometimes referred to as Action Learning, is an approach derived from Trist’s work on relations between organizations. It is contextural, insofar as it entails reconstituting the structural relations among actors in a social environment; domain-based, in that it tries to involve all affected parties and stakeholders; holographic, as each participant understands the working of the whole; and it stresses that participants act as project designers and co-researchers. The concept of organizational ecology, and the use of search conferences come out of contextural action research, which is more of a liberal philosophy, with social transformation occurring by consensus and normative incrementalism.

Radical Action Research

The Radical stream, which has its roots in Marxian ‘dialectical materialism’ and the praxis orientations of Antonio Gramsci, has a strong focus on emancipation and the overcoming of power imbalances. Participatory Action Research, often found in liberationist movements and international development circles, and Feminist Action Research both strive for social transformation via an advocacy process to strengthen peripheral groups in society.

Educational Action Research

A fourth stream, that of Educational Action Research, has its foundations in the writings of John Dewey, the great American educational philosopher of the 1920s and 30s, who believed that professional educators should become involved in community problem-solving. Its practitioners, not surprisingly, operate mainly out of educational institutions, and focus on development of curriculum, professional development, and applying learning in a social context. It is often the case that university-based action researchers work with primary and secondary school teachers and students on community projects.

Main contentsSee more from basic to advanced

Source: O’Brien, R. (2001). Um exame da abordagem metodológica da pesquisa ação [An Overview of the Methodological Approach of Action Research]. In Roberto Richardson (Ed.), Teoria e Prática da Pesquisa Ação [Theory and Practice of Action Research]. João Pessoa, Brazil: Universidade Federal da Paraíba. (English version) Available: http://www.web.ca/~robrien/papers/arfinal.html (Accessed 20/1/2002)

16 Aug 2021

16 Aug 2021

16 Aug 2021

16 Aug 2021

16 Aug 2021

16 Aug 2021