The benefits that we have described so far all make economic sense. Other arguments sometimes given for mergers are dubious. Here are a few of the dubious ones.

1. Diversification

We have suggested that the managers of a cash-rich company may prefer to see it use that cash for acquisitions rather than distribute it as extra dividends. That is why we often see cash-rich firms in stagnant industries merging their way into fresh woods and pastures new.

What about diversification as an end in itself? It is obvious that diversification reduces risk. Isn’t that a gain from merging?

The trouble with this argument is that diversification is easier and cheaper for the stockholder than for the corporation. There is little evidence that investors pay a premium for diversified firms; in fact, as we will explain in Chapter 32, discounts are more common.

The Appendix to this chapter provides a simple proof that corporate diversification does not increase value in perfect markets as long as investors’ diversification opportunities are unrestricted. This is the value-additivity principle introduced in Chapter 7.

2. Increasing Earnings per Share: The Bootstrap Game

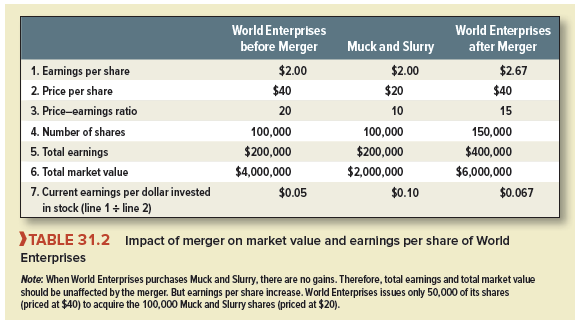

Some acquisitions that offer no evident economic gains nevertheless produce several years of rising earnings per share. To see how this can happen, let us look at the acquisition of Muck and Slurry by the well-known conglomerate World Enterprises.

The position before the merger is set out in the first two columns of Table 31.2. Because Muck and Slurry has relatively poor growth prospects, its stock’s price-earnings ratio is lower than World Enterprises’ (line 3). The merger, we assume, produces no economic benefits, and so the firms should be worth exactly the same together as they are apart. The market value of World Enterprises after the merger should be equal to the sum of the separate values of the two firms (line 6).

Since World Enterprises’ stock is selling for double the price of Muck and Slurry stock (line 2), World Enterprises can acquire the 100,000 Muck and Slurry shares for 50,000 of its own shares. Thus, World will have 150,000 shares outstanding after the merger.

Total earnings double as a result of the merger (line 5), but the number of shares increases by only 50%. Earnings per share rise from $2.00 to $2.67. We call this the bootstrap effect because there is no real gain created by the merger and no increase in the two firms’ combined value. Since the stock price is unchanged, the price-earnings ratio falls (line 3).

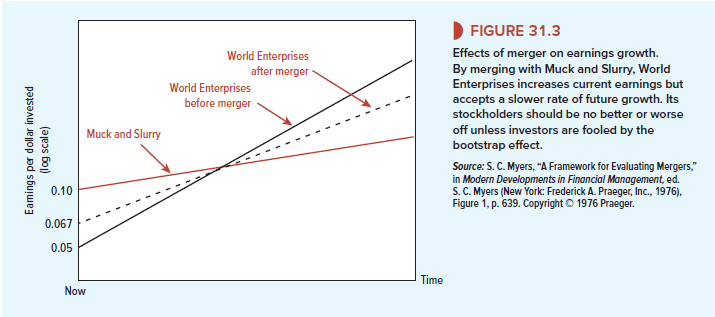

Figure 31.3 illustrates what is going on here. Before the merger $1 invested in World Enterprises bought 5 cents of current earnings and rapid growth prospects. On the other hand, $1 invested in Muck and Slurry bought 10 cents of current earnings but slower growth prospects. If the total market value is not altered by the merger, then $1 invested in the merged firm gives 6.7 cents of immediate earnings but slower growth than World Enterprises offered alone. Muck and Slurry shareholders get lower immediate earnings but faster growth. Neither side gains or loses provided everybody understands the deal.

Financial manipulators sometimes try to ensure that the market does not understand the deal. Suppose that investors are fooled by the exuberance of the president of World Enterprises and by plans to introduce modern management techniques into its new Earth Sciences Division (formerly known as Muck and Slurry). They could easily mistake the 33% postmerger increase in earnings per share for real growth. If they do, the price of World Enterprises stock rises and the shareholders of both companies receive something for nothing.

This is a “bootstrap” or “chain letter” game. It generates earnings growth not from capital investment or improved profitability, but from purchase of slowly growing firms with low price-earnings ratios. If this fools investors, the financial manager may be able to puff up stock price artificially. But to keep fooling investors, the firm has to continue to expand by merger at the same compound rate. Clearly, this cannot go on forever; one day, expansion must slow down or stop. At this point, earnings growth falls dramatically and the house of cards collapses.

This game is not often played these days, but you may still encounter managers who would rather acquire firms with low price-earnings ratios. Beware of false prophets who suggest that you can appraise mergers just by looking at their immediate impact on earnings per share.

3. Lower Financing Costs

You often hear it said that a merged firm is able to borrow more cheaply than its separate units could. In part this is true. We have already seen (in Section 15-4) that there are economies of scale in making new issues. Therefore, if firms can make fewer, larger security issues by merging, there are genuine savings.

But when people say that borrowing costs are lower for the merged firm, they usually mean something more than lower issue costs. They mean that when two firms merge, the combined company can borrow at lower interest rates than either firm could separately. This, of course, is exactly what we should expect in a well-functioning bond market. While the two firms are separate, they do not guarantee each other’s debt; if one fails, the bondholder cannot ask the other for money. But after the merger, each enterprise effectively does guarantee the other’s debt; if one part of the business fails, the bondholders can still take their money out of the other part. Because these mutual guarantees make the debt less risky, lenders demand a lower interest rate.

Does the lower interest rate mean a net gain to the merger? Not necessarily. Compare the following two situations:

- Separate issues. Firm A and firm B each make a $50 million bond issue.

- Single issue. Firms A and B merge, and the new firm AB makes a single $100 million issue.

Of course AB would pay a lower interest rate, other things being equal. But it does not make sense for A and B to merge just to get that lower rate. Although AB’s shareholders do gain from the lower rate, they lose by having to guarantee each other’s debt. In other words, they get the lower interest rate only by giving bondholders better protection. There is no net gain.

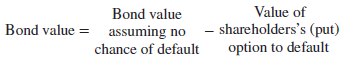

A merger of A and B increases bond value (or reduces the interest payments necessary to support a given bond value) only by reducing the value of stockholders’ option to default. In other words, the value of the default option for AB’s $100 million issue is less than the combined value of the two default options on A’s and B’s separate $50 million issues.

Now suppose that A and B each borrow $50 million and then merge. If the merger is a surprise, it is likely to be a happy one for the bondholders. The bonds they thought were guaranteed by one of the two firms end up guaranteed by both. The stockholders lose in this case because they have given bondholders better protection but have received nothing in exchange.

There is one situation in which mergers can create value by making debt safer. Consider a firm that covets interest tax shields but is reluctant to borrow more because of worries about financial distress. (This is the trade-off theory described in Chapter 18.) Merging decreases the probability of financial distress, other things equal. If it allows increased borrowing, and increased value from the interest tax shields, there can be a net gain to the merger.

There is noticeably a bundle to know about this. I assume you made certain nice points in features also.