1. Book Rate of Return

Net present value depends only on the project’s cash flows and the opportunity cost of capital. But when companies report to shareholders, they do not simply show the cash flows. They also report book—that is, accounting—income and book assets.

Financial managers sometimes use these numbers to calculate a book (or accounting) rate of return on a proposed investment. In other words, they look at the prospective book income from the investment as a proportion of the book value of the assets that the firm is proposing to acquire:

![]()

They typically compare this figure with the book rate of return that the company is currently earning.

Cash flows and book income are often very different. For example, the accountant labels some cash outflows as capital investments and others as operating expenses. The operating expenses are, of course, deducted immediately from each year’s income. The capital expenditures are put on the firm’s balance sheet and then depreciated. The annual depreciation charge is deducted from each year’s income. Thus the book rate of return depends on which items the accountant treats as capital investments and how rapidly they are depreciated.[1]

Now the merits of an investment project do not depend on how accountants classify the cash flows2 and few companies these days make investment decisions just on the basis of the book rate of return. But managers know that the company’s shareholders pay considerable attention to book measures of profitability and naturally they think (and worry) about how major projects would affect the company’s book return. Those projects that would reduce the company’s book return may be scrutinized more carefully by senior management.

You can see the dangers here. The company’s book rate of return may not be a good measure of true profitability. It is also an average across all of the firm’s activities. The average profitability of past investments is not usually the right hurdle for new investments. Think of a firm that has been exceptionally lucky and successful. Say its average book return is 24%, double shareholders’ 12% opportunity cost of capital. Should it demand that all new investments offer 24% or better? Clearly not: That would mean passing up many positive-NPV opportunities with rates of return between 12 and 24%.

We will come back to the book rate of return in Chapters 12 and 28, when we look more closely at accounting measures of financial performance.

2. Payback

We suspect that you have often heard conversations that go something like this: “We are spending $6 a week, or around $300 a year, at the laundromat. If we bought a washing machine for $800, it would pay for itself within three years. That’s well worth it.” You have just encountered the payback rule.

A project’s payback period is found by counting the number of years it takes before the cumulative cash flow equals the initial investment. For the washing machine the payback period was just under three years. The payback rule states that a project should be accepted if its payback period is less than some specified cutoff period. For example, if the cutoff period is four years, the washing machine makes the grade; if the cutoff is two years, it doesn’t.

We have no quarrel with those who use payback as a descriptive statistic. It is perfectly fine to say that the washing machine has a three-year payback. But payback should never be a rule.

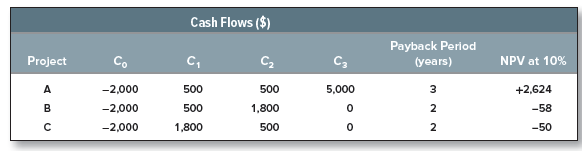

Example 5.1 • The Payback Rule

Consider the following three projects:

Project A involves an initial investment of $2,000 (C0 = -2,000) followed by cash inflows during the next three years. Suppose the opportunity cost of capital is 10%. Then project A has an NPV of +$2,624:

![]()

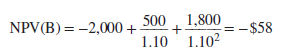

Project B also requires an initial investment of $2,000 but produces a cash inflow of $500 in year 1 and $1,800 in year 2. At a 10% opportunity cost of capital project B has an NPV of -$58:

The third project, C, involves the same initial outlay as the other two projects but its first- period cash flow is larger. It has an NPV of +$50:

![]()

The net present value rule tells us to accept projects A and C but to reject project B.

Now look at how rapidly each project pays back its initial investment. With project A, you take three years to recover the $2,000 investment; with projects B and C, you take only two years. If the firm used the payback rule with a cutoff period of two years, it would accept only projects B and C; if it used the payback rule with a cutoff period of three or more years, it would accept all three projects. Therefore, regardless of the choice of cutoff period, the payback rule gives different answers from the net present value rule.

You can see why payback can give misleading answers:

- The payback rule ignores all cash flows after the cutoff date. If the cutoff date is two years, the payback rule rejects project A regardless of the size of the cash inflow in year 3.

- The payback rule gives equal weight to all cash flows before the cutoff date. The payback rule says that projects B and C are equally attractive, but because C’s cash inflows occur earlier, C has the higher net present value at any positive discount rate.

To use the payback rule, a firm must decide on an appropriate cutoff date. If it uses the same cutoff regardless of project life, it will tend to accept many poor short-lived projects and reject many good long-lived ones.

We have had little good to say about payback. So why do many companies continue to use it? Senior managers don’t truly believe that all cash flows after the payback period are irrelevant. We suggest three explanations. First, payback may be used because it is the simplest way to communicate an idea of project profitability. Investment decisions require discussion and negotiation among people from all parts of the firm, and it is important to have a measure that everyone can understand. Second, managers of larger corporations may opt for projects with short paybacks because they believe that quicker profits mean quicker promotion. That takes us back to Chapter 1, where we discussed the need to align the objectives of managers with those of shareholders. Finally, owners of small public firms with limited access to capital may worry about their future ability to raise capital. These worries may lead them to favor rapid payback projects even though a longer-term venture may have a higher NPV.

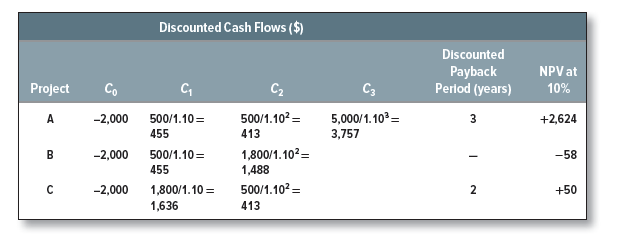

3. Discounted Payback

Occasionally companies discount the cash flows before they compute the payback period. The discounted cash flows for our three projects are as follows:

The discounted payback measure asks, How many years does the project have to last in order for it to make sense in terms of net present value? You can see that the value of the cash inflows from project B never exceeds the initial outlay and would always be rejected under the discounted payback rule. Thus a discounted payback rule will never accept a negative-NPV project. On the other hand, it still takes no account of cash flows after the cutoff date, so that good long-term projects such as A continue to risk rejection.

Rather than automatically rejecting any project with a long discounted payback period, many managers simply use the measure as a warning signal. These managers don’t unthinkingly reject a project with a long discounted payback period. Instead they check that the proposer is not unduly optimistic about the project’s ability to generate cash flows into the distant future. They satisfy themselves that the equipment has a long life and that competitors will not enter the market and eat into the project’s cash flows.

Hi there, just became aware of your blog through Google, and found that it’s really informative. I am gonna watch out for brussels. I’ll appreciate if you continue this in future. Many people will be benefited from your writing. Cheers!

I truly appreciate this post. I?¦ve been looking everywhere for this! Thank goodness I found it on Bing. You have made my day! Thx again