Some company cash flows are fixed. Others vary with the level of interest rates, rates of exchange, prices of commodities, and so on. These characteristics may not always result in the desired risk profile. For example, a company that pays a fixed rate of interest on its debt might prefer to pay a floating rate, while another company that receives cash flows in euros might prefer to receive them in yen. Swaps allow them to change their risk in these ways.

The market for swaps is huge. In 2017, the total notional amount of interest rate and currency swaps outstanding was more than $300 trillion. By far, the major part of this figure consisted of interest rate swaps. We therefore show first how interest rate swaps work and then describe a currency swap. We conclude with a brief look at some other types of swap.

1. Interest Rate Swaps

Friendly Bancorp has made a five-year, $50 million loan to fund part of the construction cost of a large cogeneration project. The loan carries a fixed interest rate of 8%. Annual interest payments are therefore $4 million. Interest payments are made annually, and all the principal will be repaid at year 5.

Suppose that instead of receiving fixed interest payments of $4 million a year, the bank would prefer to receive floating-rate payments. It can do so by swapping the $4 million, five-year annuity (the fixed interest payments) into a five-year floating-rate annuity. We show first how Friendly Bancorp can make its own homemade swap. Then we describe a simpler procedure.

The bank (we assume) can borrow at a 6% fixed rate for five years.[2] Therefore, the $4 million interest it receives can support a fixed-rate loan of 4/.06 = $66.67 million. The bank can now construct the homemade swap as follows: It borrows $66.67 million at a fixed interest rate of 6% for five years and simultaneously lends the same amount at LIBOR. We assume that LIBOR is initially 5%.[3] LIBOR is a short-term interest rate, so future interest receipts will fluctuate as the bank’s investment is rolled over.

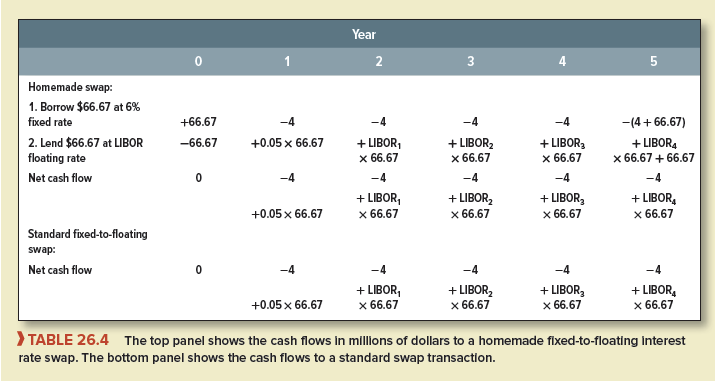

The net cash flows to this strategy are shown in the top portion of Table 26.4. Notice that there is no net cash flow in year 0 and that in year 5 the principal amount of the short-term investment is used to pay off the $66.67 million loan. What’s left? A cash flow equal to the difference between the interest earned (LIBOR x 66.67) and the $4 million outlay on the fixed loan. The bank also has $4 million per year coming in from the project financing, so it has transformed that fixed payment into a floating payment keyed to LIBOR.

Of course, there’s an easier way to do this, shown in the bottom portion of Table 26.3. The bank can just enter into a five-year swap.[4] Naturally, Friendly Bancorp takes this easier route. Let’s see what happens.

Friendly Bancorp calls a swap dealer, which is typically a large commercial or investment bank, and agrees to swap the payments on a $66.67 million fixed-rate loan for the payments on an equivalent floating-rate loan. The swap is known as a fixed-to-floating interest rate swap and the $66.67 million is termed the notional principal amount of the swap. Friendly Bancorp and the dealer are the counterparties to the swap.

The dealer is quoting a rate for five-year swaps of 6% against LIBOR.[5] This figure is sometimes quoted as a spread over the yield on U.S. Treasuries. For example, if the yield on five-year Treasury notes is 5.25%, the swap spread is .75%.

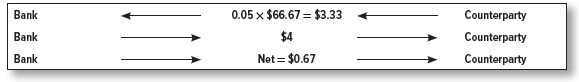

The first payment on the swap occurs at the end of year 1 and is based on the starting LIBOR rate of 5%.[6] The dealer (who pays floating) owes the bank 5% of $66.67 million, while the bank (which pays fixed) owes the dealer $4 million (6% of $66.67 million). The bank, therefore, makes a net payment to the dealer of 4 – (.05 x 66.67) = $.67 million:

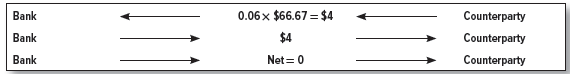

The second payment is based on LIBOR at year 1. Suppose it increases to 6%. Then the net payment is zero:

The third payment depends on LIBOR at year 2, and so on.

The notional value of this swap is $66.67 million. The fixed and floating interest rates are multiplied by the notional amount to calculate dollar amounts of fixed and floating interest. But the notional value vastly overstates the economic value of the swap. At creation, the economic value of the swap is zero because the NPV of the cash flows to each counterparty is zero. The NPV drifts away from zero as time passes and interest rates change. But the economic value will always be far less than notional value. Careless references to notional values give the impression that swap markets are impossibly gigantic; in fact, they are merely very large.

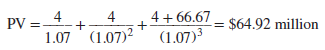

The economic value of a swap depends on the path of long-term interest rates. For example, suppose that after two years, interest rates are unchanged, so a 6% note issued by the bank would continue to trade at its face value. In this case, the swap still has zero value. (You can confirm this by checking that the NPV of a new three-year homemade swap is zero.) But if long rates increase over the two years to 7% (say), the value of a three-year note falls to

Now the fixed payments that the bank has agreed to make are less valuable and the swap is worth 66.67 – 64.92 = $1.75 million.

How do we know the swap is worth $1.75 million? Consider the following strategy:

- The bank can enter a new three-year swap deal in which it agrees to pay LIBOR on the same notional principal of $66.67 million.

- In return it receives fixed payments at the new 7% interest rate, that is, .07 X 66.67 = $4.67 per year.

The new swap cancels the cash flows of the old one, but it generates an extra $.67 million for three years. This extra cash flow is worth

![]()

Remember, ordinary interest rate swaps have no initial cost or value (NPV = 0), but their value drifts away from zero as time passes and long-term interest rates change. One counterparty wins as the other loses.

In our example, the swap dealer loses from the rise in interest rates. Dealers will try to hedge the risk of interest rate movements by engaging in a series of futures or forward contracts or by entering into an offsetting swap with a third party. As long as Friendly Bancorp and the other counterparty honor their promises, the dealer is fully protected against risk. The recurring nightmare for swap managers is that one party will default, leaving the dealer with a large unmatched position. This is another example of counterparty risk.

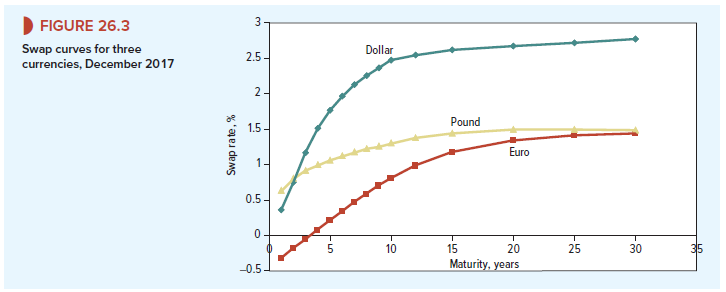

The market for interest rate swaps is large and liquid. Consequently, financial analysts often look at swap rates when they want to know how interest rates vary with maturity. For example, Figure 26.3 shows swap rates in December 2017 for the U.S. dollar, the euro, and the British pound. You can see that in each country, long-term interest rates are much higher than short-term rates, though the level of swap rates varies from one country to another.

2. Currency Swaps

We now look briefly at an example of a currency swap.

Suppose that the Possum Company needs 11 million euros to help finance its European operations. We assume that the euro interest rate is about 5%, whereas the dollar rate is about 6%. Since Possum is better known in the United States, the financial manager decides not to borrow euros directly. Instead, the company issues $10 million of five-year 6% notes in the United States. Then it arranges with a counterparty to swap this dollar loan into euros. Under this arrangement the counterparty agrees to pay Possum sufficient dollars to service its dollar loan, and in exchange Possum agrees to make a series of annual payments in euros to the counterparty.

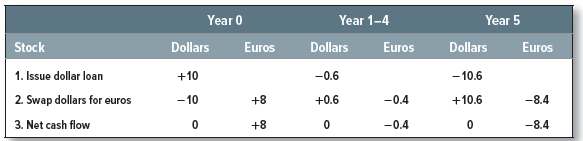

Here are Possum’s cash flows (in millions):

Look first at the cash flows in year 0. Possum receives $10 million from its issue of dollar notes, which it then pays over to the swap counterparty. In return the counterparty sends Possum a check for €8 million. (We assume that at current rates of exchange $10 million is worth €8 million.)

Now move to years 1 through 4. Possum needs to pay interest of 6% on its debt issue, which works out at .06 X 10 = $.6 million. The swap counterparty agrees to provide Possum each year with sufficient cash to pay this interest and in return Possum makes an annual payment to the counterparty of 5% of €8 million, or €.4 million. Finally, in year 5 the swap counterparty pays Possum enough to make the final payment of interest and principal on its dollar notes ($10.6 million), while Possum pays the counterparty €8.4 million.

The combined effect of Possum’s two steps (line 3) is to convert a 6% dollar loan into a 5% euro loan. You can think of the cash flows for the swap (line 2) as a series of contracts to buy euros in years 1 through 5. In each of years 1 through 4 Possum agrees to purchase $.6 million at a cost of .4 million euros; in year 5 it agrees to buy $10.6 million at a cost of 8.4 million euros.[7]

3. Some Other Swaps

While interest rate and currency swaps are the most popular type of contract, there is a wide variety of other possible swaps or related contracts. For example, in Chapter 23 we encountered credit default swaps that allow investors to insure themselves against the default on a corporate bond.

Inflation swaps allow a company to protect against inflation risk. One party in the swap receives a fixed payment while the other receives a payment that is linked to the rate of inflation. In effect, the swap creates a made-to-measure inflation-linked bond, which can be of any maturity.[8]

You can also enter into a total return swap where one party (party A) makes a series of agreed payments and the other (party B) pays the total return on a particular asset. This asset might be a common stock, a loan, a commodity, or a market index. For example, suppose that B owns $10 million of IBM stock. It now enters into a two-year swap agreement to pay A each quarter the total return on this stock. In exchange A agrees to pay B interest of LIBOR + 1%. B is known as the total return payer and A is the total return receiver. Suppose LIBOR is 5%. Then A owes B 6% of $10 million, or about 1.5% a quarter. If IBM stock returns more than this, there will be a net payment from B to A; if the return is less than 1.5%, A must make a net payment to B. Although ownership of the IBM stock does not change hands, the effect of this total return swap is the same as if B had sold the asset to A and bought it back at an agreed future date.

I truly appreciate this post. I’ve been looking everywhere for this! Thank goodness I found it on Bing. You have made my day! Thx again