Financial managers try to find the combination of securities that has the greatest overall appeal to investors—the combination that maximizes the market value of the firm. Before tackling this problem, we should check whether a policy that maximizes the total value of the firm’s securities also maximizes the wealth of the shareholders.

Let D and E denote the market values of the outstanding debt and equity of the Wapshot Mining Company. Wapshot’s 1,000 shares sell for $50 apiece. Thus,

E = 1,000 x 50 = $50,000

Wapshot has also borrowed $25,000, and so V, the aggregate market value of all Wapshot’s outstanding securities, is

V = D + E = $75,000

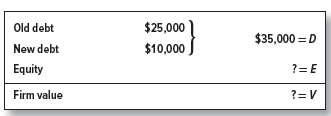

Wapshot’s stock is known as levered equity. Its stockholders face the benefits and costs of financial leverage, or gearing. Suppose that Wapshot “levers up” still further by borrowing an additional $10,000 and paying the proceeds out to shareholders as a special dividend of $10 per share. This substitutes debt for equity capital with no impact on Wapshot’s assets.

What will Wapshot’s equity be worth after the special dividend is paid? We have two unknowns, E and V:

If V is $75,000 as before, then E must be V – D = 75,000 – 35,000 = $40,000. Stockholders have suffered a capital loss that exactly offsets the $10,000 special dividend. But if V increases to, say, $80,000 as a result of the change in capital structure, then E = $45,000 and the stockholders are $5,000 ahead. In general, any increase or decrease in V caused by a shift in capital structure accrues to the firm’s stockholders. We conclude that a policy that maximizes the market value of the firm is also best for the firm’s stockholders.

This conclusion rests on two important assumptions: first, that Wapshot’s shareholders do not gain or lose from payout policy and, second, that after the change in capital structure the old and new debt are together worth $35,000.

Payout policy may or may not be relevant, but there is no need to repeat the discussion of Chapter 16. We need only note that shifts in capital structure sometimes force important decisions about payout policy. Perhaps Wapshot’s cash dividend has costs or benefits that should be considered in addition to any benefits achieved by its increased financial leverage.

Our second assumption that old plus new debt ends up worth $35,000 seems innocuous. But it could be wrong. Perhaps the new borrowing has increased the risk of the old bonds. If the holders of old bonds cannot demand a higher rate of interest to compensate for the increased risk, the value of their investment is reduced. In this case, Wapshot’s stockholders gain at the expense of the holders of old bonds even though the overall value of the firm is unchanged.

But this anticipates issues better left to Chapter 18. In this chapter, we assume that any new issue of debt has no effect on the market value of existing debt.

1. Enter Modigliani and Miller

Let us accept that the financial manager would like to find the combination of securities that maximizes the value of the firm. How is this done? MM’s answer is that the financial manager should stop worrying: In a perfect market any combination of securities is as good as another. The value of the firm is unaffected by its choice of capital structure.[1]

You can see this by imagining two firms that generate the same stream of operating income and differ only in their capital structure. Firm U is unlevered. Therefore the total value of its equity Ev is the same as the total value of the firm Vv. Firm L, on the other hand, is levered. The value of its equity is, therefore, equal to the value of the firm less the value of the debt: El = Vl – Dl.

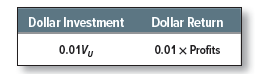

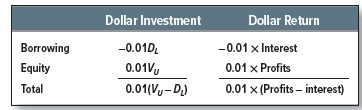

Now think which of these firms you would prefer to invest in. If you don’t want to take much risk, you can buy common stock in the unlevered firm U. For example, if you buy 1% of firm U’s shares, your investment is 0.01 Vv and you are entitled to 1% of the gross profits:

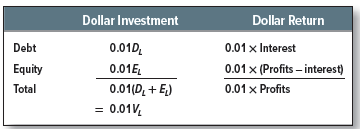

Now compare this with an alternative strategy. This is to purchase the same fraction of both the debt and the equity of firm L. Your investment and return are then:

Both strategies offer the same payoff: 1% of the firm’s profits. The law of one price tells us that in well-functioning markets two investments that offer the same payoff must have the same price. Therefore, 0.01 Vv must equal 0.01 VL: The value of the unlevered firm must equal the value of the levered firm.

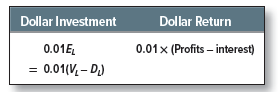

Suppose that you are willing to run a little more risk. You decide to buy 1% of the outstanding shares in the levered firm. Your investment and return are now:

Again, there is an alternative strategy. This is to borrow .01Dl on your own account and purchase 1% of the stock of the unlevered firm.[2] In this case, your strategy gives you 1% of the profits from Vv, but you have to pay interest on your loan equal to 1% of the interest that is paid by firm L. Your total investment and net return are:

Again, both strategies offer the same payoff: 1% of profits after interest. Therefore, both investments must have the same cost. The investment 0.01(Vv – DL) must equal 0.01(VL – DL) and Vv must equal VL.

It does not matter whether the world is full of risk-averse chickens or venturesome lions. All would agree that the value of the unlevered firm U must be equal to the value of the levered firm L. As long as investors can borrow or lend on their own account on the same terms as the firm, they can “undo” the effect of any changes in the firm’s capital structure. This is how MM arrived at their famous proposition 1: “The market value of any firm is independent of its capital structure.”

2. The Law of Conservation of Value

MM’s argument that debt policy is irrelevant is an application of an astonishingly simple idea. If we have two streams of cash flow, A and B, then the present value of A + B is equal to the present value of A plus the present value of B. That’s common sense: If you have a dollar in your left pocket and a dollar in your right, your total wealth is $2. We met this principle of value additivity in our discussion of capital budgeting, where we saw that the present value of two assets combined is equal to the sum of their present values considered separately.

In the present context, we are not combining assets but splitting them up. But value additivity works just as well in reverse. We can slice a cash flow into as many parts as we like; the values of the parts will always sum back to the value of the unsliced stream. (Of course, we have to make sure that none of the stream is lost in the slicing. We cannot say, “The value of a pie is independent of how it is sliced,” if the slicer is also a nibbler.)

This is really a law of conservation of value. The value of an asset is preserved regardless of the nature of the claims against it. Thus proposition 1: Firm value is determined on the left-hand side of the balance sheet by real assets—not by the proportions of debt and equity securities issued to buy the assets.

The simplest ideas often have the widest application. For example, we could apply the law of conservation of value to the choice between raising $100 million by issuing preferred stock, common stock, or some combination. The law implies that the choice is irrelevant, assuming perfect capital markets and providing that the choice does not affect the firm’s investment and operating policies. If the total value of the equity “pie” (preferred and common combined) is fixed, the firm’s owners (its common stockholders) do not care how this equity pie is sliced.

The law also applies to the mix of debt securities issued by the firm. The choices of longterm versus short-term, secured versus unsecured, senior versus subordinated, and convertible versus nonconvertible debt all should have no effect on the overall value of the firm.

Combining assets and splitting them up will not affect values as long as they do not affect investors’ choices. When we showed that capital structure does not affect choice, we implicitly assumed that both companies and individuals can borrow and lend at the same risk-free rate of interest. As long as this is so, individuals can undo the effect of any changes in the firm’s capital structure.

In practice, corporate debt is not risk-free and firms cannot escape with rates of interest appropriate to a government security. Some people’s initial reaction is that this alone invalidates MM’s proposition. It is a natural mistake, but capital structure can be irrelevant even when debt is risky.

If a company borrows money, it does not guarantee repayment: It repays the debt in full only if its assets are worth more than the debt obligation. The shareholders in the company therefore have limited liability.

Many individuals would like to borrow with limited liability. They might, therefore, be prepared to pay a premium for levered shares if the supply of levered shares were insufficient to meet their needs? But there are literally thousands of common stocks of companies that borrow. Therefore, it is unlikely that an issue of debt would induce them to pay a premium for your shares.[3] [4]

3. An Example of Proposition 1

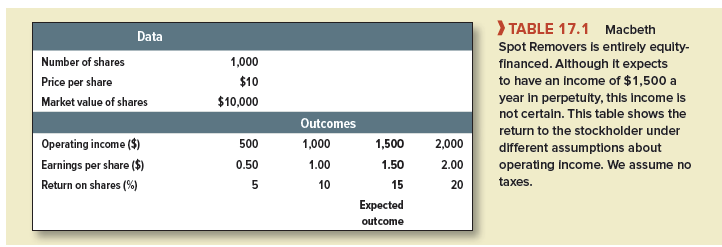

Macbeth Spot Removers is reviewing its capital structure. Table 17.1 shows its current position. The company has no leverage, and all the operating income is paid as dividends to the common stockholders (we assume still that there are no taxes). The expected earnings and dividends per share are $1.50, but this figure is by no means certain—it could turn out to be more or less than $1.50. The price of each share is $10. Because the firm expects to produce a level stream of earnings in perpetuity, the expected return on the share is equal to the earnings-price ratio, 1.50/10.00 = .15, or 15%.

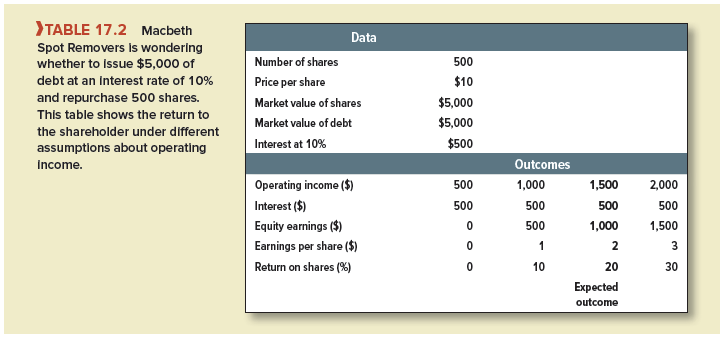

Ms. Macbeth, the firm’s president, has concluded that shareholders would be better off if the company had equal proportions of debt and equity. She therefore proposes to issue $5,000 of debt at an interest rate of 10% and use the proceeds to repurchase 500 shares. To support her proposal, Ms. Macbeth has analyzed the situation under different assumptions about operating income. The results of her calculations are shown in Table 17.2.

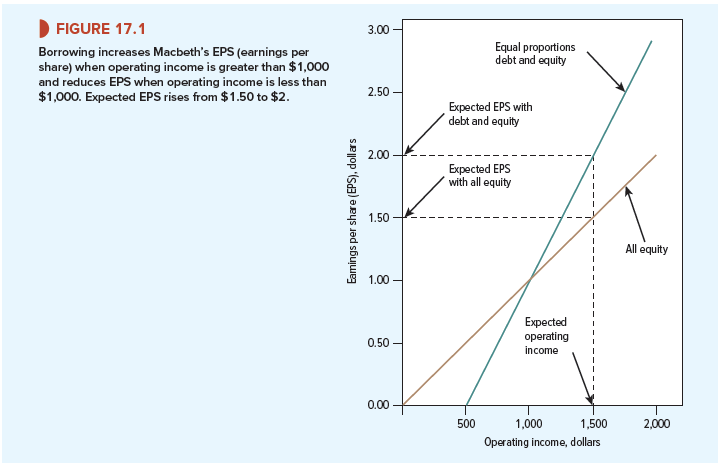

To illustrate how leverage would affect earnings per share, Ms. Macbeth has also produced Figure 17.1. The brown line shows how earnings per share would vary with operating income under the firm’s current all-equity financing. It is, therefore, simply a plot of the data in Table 17.1. The green line shows how earnings per share would vary given equal proportions of debt and equity. It is, therefore, a plot of the data in Table 17.2.

Ms. Macbeth reasons as follows: “It is clear that the effect of leverage depends on the company’s income. If income is greater than $1,000, the return to the equityholder is increased by leverage. If it is less than $1,000, the return is reduced by leverage. The return is unaffected when operating income is exactly $1,000. At this point the return on the market value of the assets is 10%, which is exactly equal to the interest rate on the debt. Our capital structure decision, therefore, boils down to what we think about the company’s prospects. Since we expect operating income to be above the $1,000 break-even point, I believe we can best help our shareholders by going ahead with the $5,000 debt issue.”

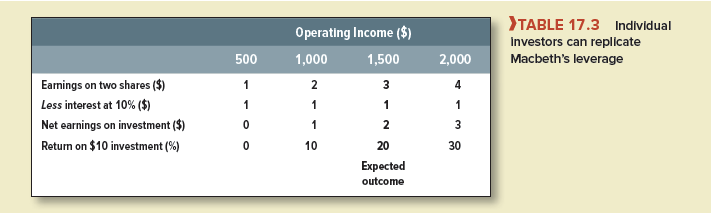

As financial manager of Macbeth Spot Removers, you reply as follows: “I agree that 1 everage will help the shareholder as long as our income is greater than $1,000. But your argument ignores the fact that Macbeth’s shareholders have the alternative of borrowing on their own account. For example, suppose that an investor puts up $10 of his or her own money, borrows a further $10, and then invests the total in two unlevered Macbeth shares. The payoff on the investment varies with Macbeth’s operating income [as shown in Table 17.3]. This is exactly the same set of payoffs as the investor would get by buying one share in the levered company. [Compare the last two lines of Tables 17.2 and 17.3.] Therefore, a share in the levered company must also sell for $10. If Macbeth goes ahead and borrows, it will not allow investors to do anything that they could not do already, and so it will not increase value.”

The argument that you are using is exactly the same as the one MM used to prove proposition 1.

Well I truly liked reading it. This tip procured by you is very useful for good planning.