Boeing has 596 million shares outstanding. Shareholders include large pension funds and insurance companies that each own millions of shares, as well as individuals who own a handful. If you owned one Boeing share, you would own .0000002% of the company and have a claim on the same tiny fraction of its profits. Of course, the more shares you own, the larger your “share” of the company.

If Boeing wishes to raise new capital, it can do so either by borrowing or by selling new shares to investors. Sales of shares to raise new capital are said to occur in the primary market. But most trades in Boeing take place on the stock exchange, where investors buy and sell existing Boeing shares. Stock exchanges are really markets for secondhand shares, but they prefer to describe themselves as secondary markets, which sounds more important.

The two principal U.S. stock exchanges are the New York Stock Exchange and Nasdaq. Both compete vigorously for business and just as vigorously tout the advantages of their trading systems. In addition to the NYSE and Nasdaq, there are electronic communication networks (ECNs) that connect traders with each other. Large U.S. companies may also arrange for their shares to be traded on foreign exchanges, such as the London exchange or the Euronext exchange in Paris. At the same time, many foreign companies are listed on the U.S. exchanges. For example, the NYSE trades shares in Sony, Royal Dutch Shell, Canadian Pacific, Tata Motors, Deutsche Bank, Telefonica Brasil, China Eastern Airlines, and more than 500 other companies.

Suppose that Ms. Jones, a long-time Boeing shareholder, no longer wishes to hold her shares. She can sell them via the stock exchange to Mr. Brown, who wants to increase his stake in the firm. The transaction merely transfers partial ownership of the firm from one investor to another. No new shares are created, and Boeing will neither care nor know that the trade has taken place.

Ms. Jones and Mr. Brown do not trade the Boeing shares themselves. Instead, their orders must go through a brokerage firm. Ms. Jones, who is anxious to sell, might give her broker a market order to sell stock at the best available price. On the other hand, Mr. Brown might state a price limit at which he is willing to buy Boeing stock. If his limit order cannot be executed immediately, it is recorded in the exchange’s limit order book until it can be executed.

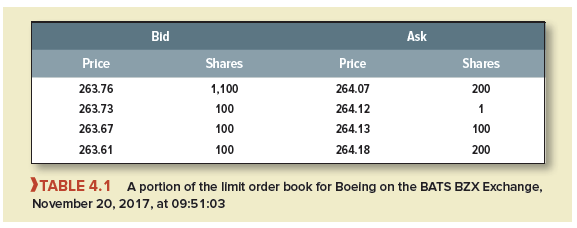

Table 4.1 shows a portion of the limit order book for Boeing from the BATS Exchange, one of the largest electronic markets. The bid prices on the left are the prices (and number of shares) at which investors are currently willing to buy. The ask prices on the right are those at which investors are prepared to sell. The prices are arranged from best to worst, so the highest bids and lowest asks are at the top of the list. The broker might electronically enter Ms. Jones’s market order to sell 100 shares on the BATS Exchange, where it would be matched with the best offer to buy, which at that moment was $263.76 a share. A market order to buy would be matched with the best ask price, $264.07. The bid-ask spread at that moment was, therefore, 31 cents per share.

When they transact on the NYSE or one of the electronic markets, Brown and Jones are participating in a huge auction market in which the exchange matches up the orders of thousands of investors. Most major exchanges around the world, including the Tokyo, Shanghai, London stock exchanges and the Deutsche Borse, are also auction markets, but the auctioneer in these cases is a computer.1 This means that there is no stock exchange floor to show on the evening news and no one needs to ring a bell to start trading.

Nasdaq is not an auction market. All trades on Nasdaq take place between the investor and one of a group of professional dealers who are prepared to buy and sell stock. Dealer markets are common for other financial instruments. For example, most bonds are traded in dealer markets.

1. Trading Results for Boeing

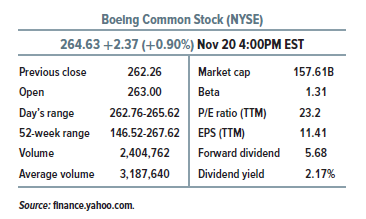

You can track trades in Boeing or other public corporations on the Internet. For example, if you go to finance.yahoo.com and enter the ticker symbol BA under “Quote Lookup,” you will see results like the table below.2 We will focus here on some of the more important entries.

Boeing’s closing price on November 20, 2017, was $264.63, up $2.37, or .90% from the previous day’s close. Boeing had 595.58 million shares outstanding, so its market cap (shorthand for market capitalization) was 595.58 X $264.63 = $157.61 billion.

Boeing’s earnings per share (EPS) over the previous 12 months were $11.41 (“TTM” stands for “trailing 12 months”). The ratio of stock price to EPS (the P/E ratio) was 23.2. Notice that this P/E ratio uses past EPS. P/E ratios using forecasted EPS are generally more useful. Security analysts forecasted an increase in Boeing’s EPS to 11.68 per share for 2018, which gives a forward P/E of 22.7.3

Boeing paid a cash dividend of $5.68 per share per year, so its dividend yield (the ratio of dividend to price) was 2.17%.

Boeing’s beta of 1.31 measures the market risk of Boeing’s stock. We explain betas in Chapter 7.

Boeing stock was a wonderful investment in 2017: Its price was up 81% in the 12 months previous to the quotes summarized here. Buying stocks is a risky occupation, however. Take GE as an example. GE used to be one of the most powerful and admired U.S. companies. But GE stock fell by 40% over the 12 months ending on November 16, 2017—a period in which the S&P 500 market index gained 18.5%. The stock fell by 23% in the last month of that period when its new CEO cut GE’s dividend in half and announced a plan for drastic restructuring. There weren’t many GE stockholders piping up at cocktail parties over the 2017 holiday season; they either kept quiet or were not invited.

Most of the trading on the NYSE and Nasdaq is in ordinary common stocks, but other securities are traded also, including preferred shares, which we cover in Chapter 14, and warrants, which we cover in Chapter 21. Investors can also choose from hundreds of exchange-traded funds (ETFs), which are portfolios of stocks that can be bought or sold in a single trade. With a few exceptions ETFs are not actively managed. Many simply aim to track a well-known market index such as the Dow Jones Industrial Average or the S&P 500. Others track specific industries or commodities. (We discuss ETFs more fully in Chapter 14.) You can also buy shares in closed-end mutual funds[1] that invest in portfolios of securities. These include country funds, for example, the Mexico and India funds, that invest in portfolios of stocks in specific countries. Unlike ETFs, most closed-end funds are actively managed and seek to “beat the market.”

As a Newbie, I am continuously exploring online for articles that can aid me. Thank you

Good write-up, I am normal visitor of one¦s blog, maintain up the nice operate, and It’s going to be a regular visitor for a lengthy time.