1. A Question Expressing a Knowledge Project

To construct a research problem is to elaborate a question or problematic through which the researcher will construct or discover reality. The question produced links or examines theoretical, methodological or empirical elements.

The theoretical elements of the research problem may be concepts (collective representation, change, learning, collective knowledge or cognitive schemes, for example), explicative or descriptive models of phenomena (for instance, innovation processes in an unstable environment or learning processes in groups) or theories (such as Festinger’s theory of cognitive dissonance). Some authors place particular emphasis on the primacy of the question’s theoretical dimension. However, in our opinion, we can also construct a research problem by linking or examining theoretical elements, empirical elements or methodological elements. For example, empirical elements could be a decision taken by a board of directors, a result such as the performance of a business, or facts or events; methodological elements could include the method of cognitive mapping, a scale for measuring a concept or a method to support decision-making processes.

A theoretical, empirical or methodological element does not, in itself, constitute a research problem. To take up our first examples, neither ‘the Cuban missile crisis’ nor ‘a method of constructing the representations held by managers’ constitute in themselves a research problem. They are not questions through which we can construct or discover reality. However, examining these elements or the links between them can enable the creation or discovery of reality, and therefore does constitute a research problem. So, ‘How can we move beyond the limits of cognitive mapping to elicit the representations held by managers?’ or ‘How was the decision made to blockade during the Cuban crisis?’ do constitute research problems.

Examining facts, theoretical or methodological elements, or the links between them enables a researcher to discover or create other theoretical or methodological elements or even other facts. For instance, researchers may hope their work will encourage managers to reflect more about their vision of company strategy. In this case, they will design research that will create facts and arouse reactions that will modify social reality (Cossette and Audet, 1992). The question the researcher formulates therefore indirectly expresses the type of contribution the research will make: a contribution that is for the most part theoretical, methodological or empirical. In this way, we can talk of different types of research problem (see following examples).

Example: Different types of research problems

- ‘What does a collective representation in an organization consist of, what is its nature and its constituent elements, and how does it emerge from the supposedly differing representations held by its members?’ This research problem principally links concepts, and may be considered as theoretical.

- ‘How can we move beyond the limits of cognitive mapping in eliciting the representations held by managers?’ In this case, the research problem would be described as methodological.

- ‘How can we accelerate the process of change in company X?’ The research problem here is empirical (the plans for change at X). The contribution may be both methodological (creating a tool to assist change) and empirical (speeding up change in company X).

The theoretical, methodological or empirical elements that are created or discovered by the researcher (and which constitute the research’s major contribution) will enable reality to be explained, predicted, understood or changed. In this way the research will meet the ultimate goals of management science.

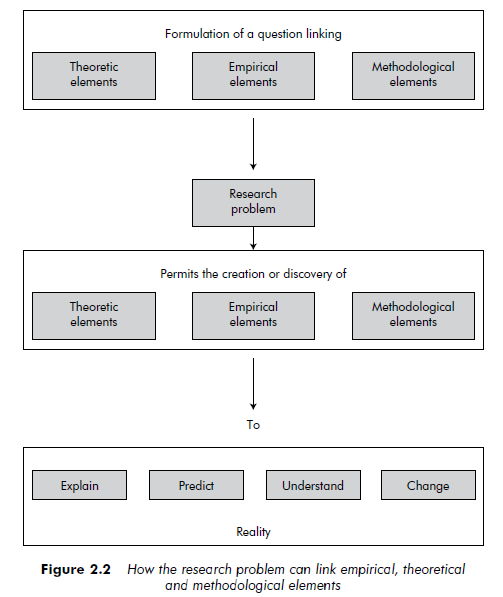

To sum up, constructing a research problem consists of formulating a question linking theoretical, empirical or methodological elements, a question which will enable the creation or discovery of other theoretical, empirical or methodological elements that will explain, predict, understand or change reality (see Figure 2.2).

2. Different Research Problems for Different Knowledge Goals

A knowledge goal assumes a different signification according to the researcher’s epistemological assumptions. The type of knowledge researchers seek, and that of their research problem, will differ depending on whether they hold a positivist, interpretative or constructivist vision of reality.

For a positivist researcher, the research problem consists principally of examining facts so as to discover the underlying structure of reality. For an interpretative researcher, it is a matter of understanding a phenomenon from the inside in an effort to understand the significations people attach to reality, as well as their motivations and intentions. Finally, for constructivist researchers, constructing a research problem consists of elaborating a knowledge project which they will endeavor to satisfy by means of their research.

These three different epistemological perspectives are based on different visions of reality and on the researcher’s relationship with that reality. Consequently, they each attribute a different origin and role to the research problem, and give it a different position in the research process.

The research problem and, therefore, the process by which it is formulated will differ according to the type of knowledge a researcher wishes to produce.

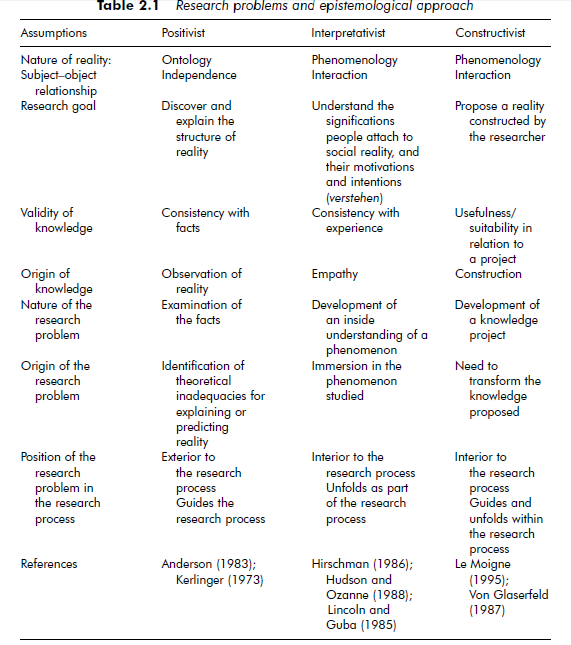

The relationship between the epistemological assumptions of the researcher and the type of research problem they will tend to produce is presented in Table 2.1. The categories presented here can only be indicative and theoretical. Their inclusion is intended to provide pointers that researchers can use in identifying their presuppositions, rather than to suggest they are essential considerations in the construction of a research problem. Most research problems in management sciences are in fact rooted in these different perspectives.

However, once a research problem has been temporarily defined during the research process, it is useful to try to understand the assumptions underlying it, in order to fully appreciate their implications for the research design and results.

2.1. A positivist approach

Positivists consider that reality has its own essence, independently of what individuals perceive – this is what we call an ontological hypothesis. Furthermore, this reality is governed by universal laws: real causes exist and causality is the rule of nature – the determinist hypothesis. To understand reality, we must then try to explain it, to discover the simple and systematic associations between variables underlying a phenomenon (Kerlinger, 1973).

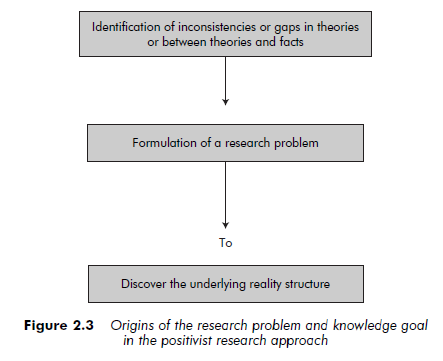

From the positivist viewpoint, then, the research problem consists essentially of examining facts. Researchers construct their research problem by identifying inadequacies or inconsistencies in existing theories, or between theories and facts (Landry, 1995). The results of the research will be aimed at resolving or correcting these inadequacies or inconsistencies so as to improve our knowledge about the underlying structure of reality (see Figure 2.3).

The nature of the knowledge sought and of the research problem in the positivist epistemology imply that, in the research process, the research problem should be external to scientific activity. Ideally, the research problem is independent of the process that led the researcher to pose it. The research problem then serves as a guide to the elaboration of the architecture and methodology of the research.

2.2. An interpretativist approach

For interpretativists, reality is essentially mental and perceived – the phenomenological hypothesis – and the researcher and the subjects studied interact with each other – the hypothesis of interactivity (Hudson and Ozanne, 1988). In accordance with these hypotheses, interpretativists’ knowledge goal is not to discover reality and the laws underlying it, but to develop an understanding (verstehen) of social realities. This means developing an understanding of the culturally shared meanings, the intentions and motives of those involved in creating these social realities, and the context in which these constructions are taking place (Hudson and Ozanne, 1988; Schwandt, 1994).

In this perspective, the research process is not directed by an external knowledge goal (as in the positivist research approach), but consists of developing an understanding of the social reality experienced by the subjects of the study. The research problem, therefore, does not involve examining facts to discover their underlying structure, but understanding a phenomenon from the viewpoint of the individuals involved in its creation – in accordance with their own language, representations, motives and intentions (Hudson and Ozanne, 1988; Hirschman, 1986).

The research problem thus unfolds from researcher’s immersion in the phenomenon he or she wishes to study (efforts to initiate change in a university, for example). By immersing him or herself in the context, the researcher will be able to develop an inside understanding of the social realities he or she studies. In particular, the researcher will recognize and grasp the participant’s problems, motives and meanings (for instance, what meanings actors attach to the university president’s efforts to initiate change, and how they react to them).

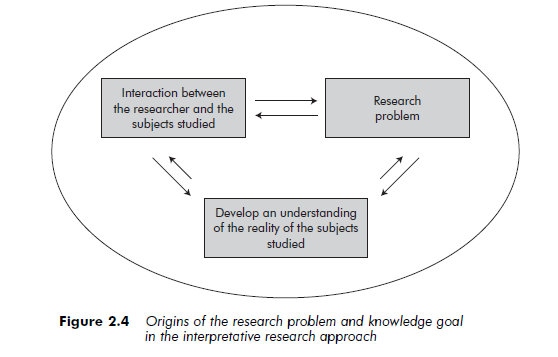

Here, constructing a research problem does not equate to elaborating a general theoretical problematic that will guide the research process, with the ultimate aim of explaining or predicting reality. The researcher begins from an interest in a phenomenon, and then decides to develop an inside understanding of it. The specific research problem emerges as this understanding develops. Although interpretativists may enter their research setting with some prior knowledge of it, and a general plan, they do not work from established guidelines or strict research protocols. They seek instead to constantly adapt to the changing environment, and to develop empathy for its members (Hudson and Ozanne, 1988). From the interpretative perspective, this is the only way to understand the social realities that people create and experience (Lincoln and Guba, 1985). The research problem will then take its final form semiconcomitantly with the outcome of the research, when researchers have developed an interpretation of the social reality they have observed or in which they have participated (see Figure 2.4).

This is, of course, a somewhat simplistic and extreme vision of interpreta- tivism. Researchers often begin with a broadly defined research problem that will guide their observations (see Silverman, 1993, for example). This is, however, difficult to assess as most interpretative research, published in American journals at least, are presented in the standard academic format: The research problem is announced in the introduction to the article, and often positioned in relation to existing theories and debates, which can give the mistaken impression that the researchers have clearly defined their research problem before beginning their empirical investigation, as in the positivist approach.

2.3. A constructivist research approach

For the constructivists, knowledge and reality are created by the mind. There is no unique real world that pre-exists independently from human mental activity and language: all observation depends on its observer – including data, laws of nature and external objects (Segal, 1990: 21). In this perspective, ‘reality is pluralistic – i.e. it can be expressed by a different symbol and language system – but also plastic – i.e. it is shaped to fit the purposeful acts of intentional human agents’ (Schwandt, 1994: 125). The knowledge sought by constructivists is therefore contextual and relative, and above all instrumental and goal-oriented (Le Moigne, 1995). Constructivist researchers construct their own reality, starting from and drawing on their own experience in the context ‘in which they act’ (Von Glaserfeld, 1988: 30). The dynamics and the goal of the knowledge construction are always linked to the intentions and the motives of the researcher, who experiments, acts and seeks to know. Eventually, the knowledge constructed should serve the researcher’s contingent goals: it must be operational. It will then be evaluated according to whether it has fulfilled the researcher’s objectives or not – that is, according to a criterion of appropriateness (Le Moigne, 1995).

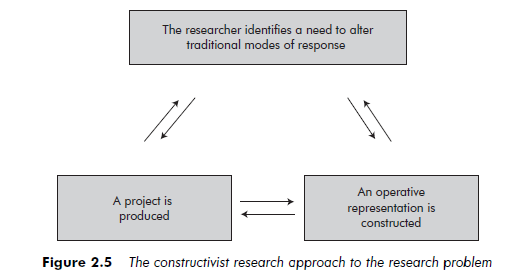

From this perspective, constructing the research problem is to design a goal- oriented project. This project originates in the identification of a need to alter traditional responses to a given context – to change accepted modes of action or of thought. The construction of the research problem takes place gradually as the researcher develops his or her own experience of the research. The project is in fact continually redefined as the researcher interacts with the reality studied (Le Moigne, 1995). Because of this conjectural aspect of the constructivist process of constructing knowledge, the research problem only appears after the researcher has enacted a clear vision of the project and has stabilized his or her own construction of reality.

Thus, as in the interpretative research approach, the constructivist’s research problem is only fully elaborated at the end of the research process. In the constructivist research approach, however, the process of constructing the research problem is guided by the researcher’s initial knowledge project (see Figure 2.5). The researcher’s subjectivity and purposefulness are then intrinsic to the constructivist project. This intentional dimension of the constructivist research approach departs from the interpretative one. The interpretative research process is not aimed at transforming reality and knowledge and does not take into account the goal-oriented nature of knowledge.

The type of research problem produced, and the process used to construct it, will vary depending on the nature of the knowledge sought and the underlying vision of reality. As we pointed out earlier, the categories we have presented are representative only. If a researcher does not strongly support a particular epistemological view from the outset, he or she could construct a research problem by working from different starting points. In such a process, it is unlikely that the researcher will follow a linear and pre-established dynamics.

Source: Thietart Raymond-Alain et al. (2001), Doing Management Research: A Comprehensive Guide, SAGE Publications Ltd; 1 edition.

26 Jul 2021

26 Jul 2021

26 Jul 2021

26 Jul 2021

26 Jul 2021

26 Jul 2021