It’s been said that a camel looks like a horse designed by a committee. If a firm made every decision piecemeal, it would end up with a financial camel. That is why smart financial managers also need to plan for the long term and to consider the financial actions that will be needed to support the company’s long-term growth. Here is where finance and strategy come together. A coherent long-term plan demands an understanding of how the firm can generate superior returns by its choice of industry and by the way that it positions itself within that industry.

Long-term planning involves capital budgeting on a grand scale. It focuses on the investment by each line of business and avoids getting bogged down in details. Of course, some individual projects may be large enough to have significant individual impact. For example, the telecom giant Verizon has spent billions of dollars to deploy fiber-optic-based broadband technology to its residential customers. You can bet that this project was explicitly analyzed as part of its long-range financial plan. Normally, however, planners do not work on a project- by-project basis. Instead, they are content with rules of thumb that relate average levels of fixed and short-term assets to annual sales, and do not worry so much about seasonal variations in these relationships. In such cases, the likelihood that accounts receivable may rise as sales peak in the holiday season would be a needless detail that would distract from more important strategic decisions.

1. Why Build Financial Plans?

Firms spend considerable time and resources in long-term planning. What do they get for this investment?

Contingency Planning Planning is not just forecasting. Forecasting concentrates on the most likely outcomes, but planners worry about unlikely events as well as likely ones. If you think ahead about what could go wrong, then you are less likely to ignore the danger signals and you can respond faster to trouble.

Companies have developed a number of ways of asking “what if’ questions about both individual projects and the overall firm. For example, managers often work through the consequences of their decisions under different scenarios. One scenario might envisage high interest rates contributing to a slowdown in world economic growth and lower commodity prices. A second scenario might involve a buoyant domestic economy, high inflation, and a weak currency. The idea is to formulate responses to inevitable surprises. What will you do, for example, if sales in the first year turn out to be 10% below forecast? A good financial plan should help you adapt as events unfold.

Considering Options Planners need to think whether there are opportunities for the company to exploit its existing strengths by moving into a wholly new area. Often they may recommend entering a market for “strategic” reasons—that is, not because the immediate investment has a positive net present value but because it establishes the firm in a new market and creates options for possibly valuable follow-on investments.

For example, Verizon’s costly fiber-optic initiative gives the company the real option to offer additional services that may be highly valuable in the future, such as the rapid delivery of an array of home entertainment services. The justification for the huge investment lies in these potential growth options.

Forcing Consistency Financial plans draw out the connections between the firm’s plans for growth and the financing requirements. For example, a forecast of 25% growth might require the firm to issue securities to pay for necessary capital expenditures, while a 5% growth rate might enable the firm to finance these expenditures by using only reinvested profits.

Financial plans should help to ensure that the firm’s goals are mutually consistent. For example, the chief executive might say that she is shooting for a profit margin of 10% and sales growth of 20%, but financial planners need to think about whether the higher sales growth may require price cuts that will reduce the profit margin.

Moreover, a goal that is stated in terms of accounting ratios is not operational unless it is translated back into what that means for business decisions. For example, a higher profit margin can result from higher prices, lower costs, or a move into new, high-margin products. Why then do managers define objectives in this way? In part, such goals may be a code to communicate real concerns. For example, a target profit margin may be a way of saying that in pursuing sales growth, the firm has allowed costs to get out of control. The danger is that everyone may forget the code and the accounting targets may be seen as goals in themselves. No one should be surprised when lower-level managers focus on the goals for which they are rewarded. For example, when Volkswagen set a goal of a 6.5% profit margin, some VW groups responded by developing and promoting expensive, high-margin cars. Less attention was paid to marketing cheaper models, which had lower profit margins but higher sales volume. As soon as this became apparent, Volkswagen announced that it would de-emphasize its profit margin goal and would instead focus on return on investment. It hoped that this would encourage managers to get the most profit out of every dollar of invested capital.

2. A Long-Term Financial Planning Model for Dynamic Mattress

Financial planners often use a financial planning model to help them explore the consequences of alternative strategies. We will drop in again on the financial manager of Dynamic Mattress to see how she uses a simple spreadsheet program to draw up the firm’s long-term plan.

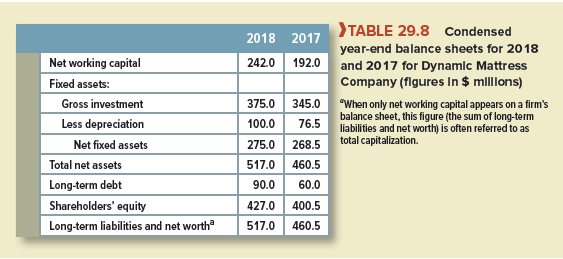

Long-term planning is concerned with the big picture. Therefore, when constructing longterm planning models it is generally acceptable to collapse all current assets and liabilities into a single figure for net working capital. Table 29.8 replaces Dynamic’s latest balance sheets with condensed versions that report only net working capital rather than individual current assets or liabilities.

Suppose that Dynamic’s analysis of the industry leads it to forecast a 20% annual growth in the company’s sales and profits over the next five years. Can the company realistically expect to finance this out of retained earnings and borrowing, or should it plan for an issue of equity? Spreadsheet programs are tailor-made for such questions. Let’s investigate.

The basic sources and uses relationship tells us that the sources of funds must be sufficient to cover the uses. If the company’s operations do not provide sufficient cash to pay for the uses, then it will need to raise additional capital from external sources. Dynamic’s external capital requirement equals the difference between the cash that the firm will need for its investments and dividend payments and the funds that it will generate from its business operations.

External capital required = (investment in net working capital + investment in fixed assets

+ dividends) – cash flow from operations

Thus, there are three steps to finding how much extra capital Dynamic will need and the implications for its debt ratio.

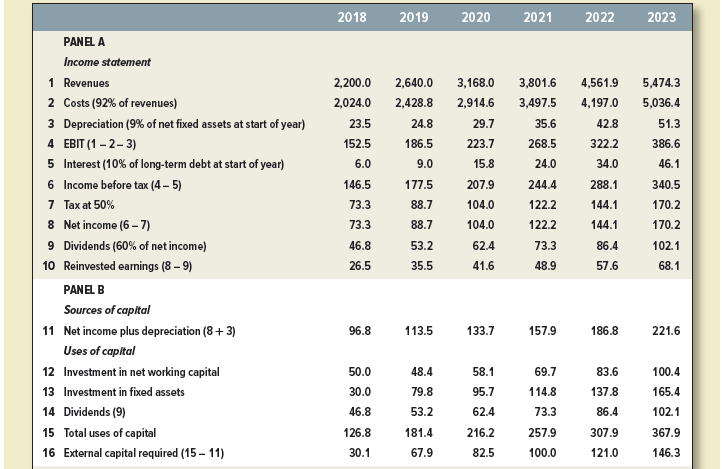

Step 1 Project next year’s net income plus depreciation, assuming the planned 20% increase in revenues. These projections are shown in Panel A of Table 29.9.The first column shows net income for Dynamic in the latest year (2018) and is taken from Table 29.1. The remaining columns show the forecasted values for the following five years.

Step 2 Project what additional investment in net working capital and fixed assets will be needed to support this increased activity and how much of the net income will be paid out as dividends. The sum of these expenditures gives you the total uses of capital. If the total uses of capital exceed the cash flow generated by operations, Dynamic will need to raise additional long-term capital. Panel B of Table 29.9 shows these capital requirements. The first column shows that in 2018 Dynamic needed to raise $30 million of new capital. The remaining columns forecast its capital needs for the following five years. For example, you can see that Dynamic will need to issue $67.9 million of debt in 2019 if it is to expand at the planned rate and not sell more shares.

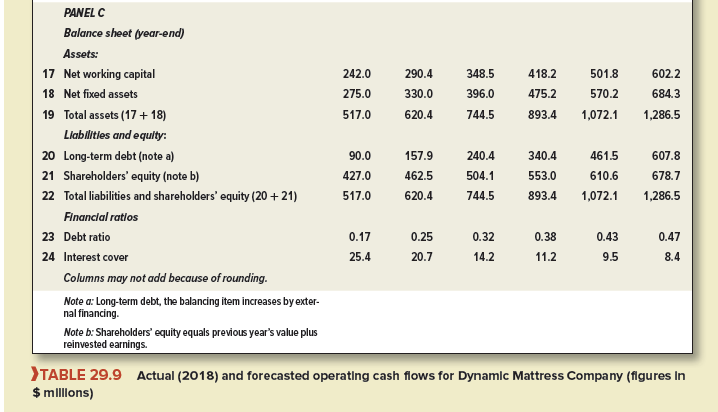

Step 3 Finally, construct a forecast, or pro forma, balance sheet that incorporates the additional assets and the new levels of debt and equity. For example, the first column of Panel C of Table 29.9 shows the latest condensed balance sheet for Dynamic Mattress. The remaining columns show that the company’s equity grows by the additional retained earnings (net income less dividends), while long-term debt increases steadily to $607.8 million.

Over the five-year period, Dynamic Mattress is forecasted to borrow an additional $517.8 million, and by year 2023, its debt ratio will have risen from 17% to 47%. The interest payments would still be comfortably covered by earnings, and most financial managers could live with this amount of debt. However, the company could not continue to borrow at that rate beyond five years, and the debt ratio might be close to the limit set by the company’s banks and bondholders.

An obvious alternative is for Dynamic to issue a mix of debt and equity, but there are other possibilities that the financial manager may want to explore. One option may be to hold back dividends during this period of rapid growth. An alternative may be to investigate whether the company could cut back on net working capital. For example, it may be able to economize on inventories or speed up the collection of receivables. The model makes it easy to examine these alternatives.

We stated earlier that financial planning is not just about exploring how to cope with the most likely outcomes. It also needs to ensure that the firm is prepared for unlikely or unexpected ones. For example, management would certainly wish to check that Dynamic Mattress could cope with a cyclical decline in sales and profit margins. Sensitivity analysis or scenario analysis can help to do this.

3. Pitfalls in Model Design

The Dynamic Mattress model that we have developed is too simple for practical application. You probably have already thought of several ways to improve it—by keeping track of the outstanding shares, for example, and printing out earnings and dividends per share. Or you might want to distinguish between short-term lending and borrowing opportunities, now buried in working capital.

The model that we developed for Dynamic Mattress is known as a percentage of sales model. Almost all the forecasts for the company are proportional to the forecasted level of sales. However, in reality many variables will not be proportional to sales. For example, important components of working capital such as inventory and cash balances will generally rise less rapidly than sales. In addition, fixed assets such as plant and equipment are not usually added in small increments as sales increase. The Dynamic Mattress plant may well be operating at less than full capacity, so that the company can initially increase output without any additions to capacity. Eventually, however, if sales continue to increase, the firm may need to make a large new investment in plant and equipment.

But beware of adding too much complexity: There is always the temptation to make a model bigger and more detailed. You may end up with an exhaustive model that is too cumbersome for routine use. The fascination of detail, if you give in to it, distracts attention from crucial decisions like stock issues and payout policy.

4. Choosing a Plan

Financial planning models help the manager to develop consistent forecasts of crucial financial variables. For example, if you wish to value Dynamic Mattress, you need forecasts of future free cash flows. These are easily derived up to the end of the planning period from our financial planning model.[1] However, a planning model does not tell you whether the plan is optimal. It does not even tell you which alternatives are worth examining. For example, we saw that Dynamic Mattress is planning for a rapid growth in sales and earnings per share. But is that good news for the shareholders? Well, not necessarily; it depends on the opportunity cost of the capital that Dynamic Mattress needs to invest. If the new investment earns more than the cost of capital, it will have a positive NPV and add to shareholder wealth. If the investment earns less than the cost of capital, shareholders will be worse off, even though the company expects steady growth in earnings.

The capital that Dynamic Mattress needs to raise depends on its decision to pay out 60% of its earnings as a dividend. But the financial planning model does not tell us whether this dividend payment makes sense or what mixture of equity or debt the company should issue. In the end the management has to decide. We would like to tell you exactly how to make the choice, but we can’t. There is no model that encompasses all the complexities encountered in financial planning and decision making.

As a matter of fact, there never will be one. This bold statement is based on Brealey, Myers, and Allen’s Third Law:[2]

Axiom: The number of unsolved problems is infinite.

Axiom: The number of unsolved problems that humans can hold in their minds is at any time limited to 10.

Law: Therefore in any field there will always be 10 problems that can be addressed but that have no formal solution.

BMA’s Third Law implies that no model can find the best of all financial strategies.[3]

I think this site holds some really excellent information for everyone. “As we grow oldthe beauty steals inward.” by Ralph Waldo Emerson.