A company’s first public issue of stock is seldom its last. As the firm grows, it is likely to make further issues of debt and equity. Public companies can issue securities either by offering them to investors at large or by making a rights issue that is limited to existing stockholders. We begin by describing general cash offers, which are now used for almost all debt and equity issues in the United States. We then describe rights issues, which are widely used in other countries for issues of common stock.

1. General Cash Offers

When a corporation makes a general cash offer of debt or equity in the United States, it goes through much the same procedure as when it first went public. In other words, it registers the issue with the SEC[1] and then sells the securities to an underwriter (or a syndicate of underwriters), who in turn offers the securities to the public. Before the price of the issue is fixed, the underwriter will build up a book of likely demand for the securities, just as in the case of Marvin’s IPO.

The SEC’s Rule 415 allows large companies to file a single registration statement covering financing plans for up to three years into the future. The actual issues can then be done with scant additional paperwork, whenever the firm needs the cash or thinks it can issue securities at an attractive price. This is called shelf registration—the registration statement is “put on the shelf,” to be taken down and used as needed.

Think of how you as a financial manager might use shelf registration. Suppose your company is likely to need up to $200 million of new long-term debt over the next year or so. It can file a registration statement for that amount. It then has prior approval to issue up to $200 million of debt, but it isn’t obligated to issue a penny. Nor is it required to work through any particular underwriters; the registration statement may name one or more underwriters the firm thinks it may work with, but others can be substituted later.

Now you can sit back and issue debt as needed, in bits and pieces if you like. Suppose Morgan Stanley comes across an insurance company with $10 million ready to invest in corporate bonds. Your phone rings. It’s Morgan Stanley offering to buy $10 million of your bonds, priced to yield, say, 8.5%. If you think that’s a good price, you say OK and the deal is done, subject only to a little additional paperwork. Morgan Stanley then resells the bonds to the insurance company, it hopes at a higher price than it paid for them, thus earning an intermediary’s profit.

Here is another possible deal: Suppose that you perceive a window of opportunity in which interest rates are temporarily low. You invite bids for $100 million of bonds. Some bids may come from large investment banks acting alone; others may come from ad hoc syndicates. But that’s not your problem; if the price is right, you just take the best deal offered.

Not all companies eligible for shelf registration actually use it for all their public issues. Sometimes they believe they can get a better deal by making one large issue through traditional channels, especially when the security to be issued has some unusual feature or when the firm believes that it needs the investment banker’s counsel or stamp of approval on the issue. Consequently, shelf registration is less often used for issues of common stock or convertible securities than for garden-variety corporate bonds.

2. International Security Issues

Instead of borrowing in their local market, companies often issue so-called foreign bonds in another country’s domestic market, in which case the issue will be governed by the rules of that country.

A second alternative is to make an issue of eurobonds, which is underwritten by a group of international banks and offered simultaneously to investors in a number of countries. The borrower must provide a prospectus or offering circular that sets out the detailed terms of the issue. The underwriters will then build up a book of potential orders, and finally, the issue will be priced and sold. Very large debt issues may be sold as global bonds, with one part sold internationally in the eurobond market and the remainder sold in the company’s domestic market.

Equity issues too may be sold overseas. Traditionally, New York has been the natural home for such issues, but in recent years, many companies have preferred to list in London or Hong Kong. This has led many U.S. observers to worry that New York may be losing its competitive edge to other financial centers.

3. The Costs of a General Cash Offer

Whenever a firm makes a cash offer of securities, it incurs substantial administrative costs, and it needs to compensate the underwriters by selling them securities below the price that they expect to receive from investors.

In addition to these direct costs, the offer price for seasoned stock issues is on average set at about 3% below the previous night’s close.[2] While this underpricing is far less than in the case of an IPO, it remains a significant proportion of the cost of an issue of stock.

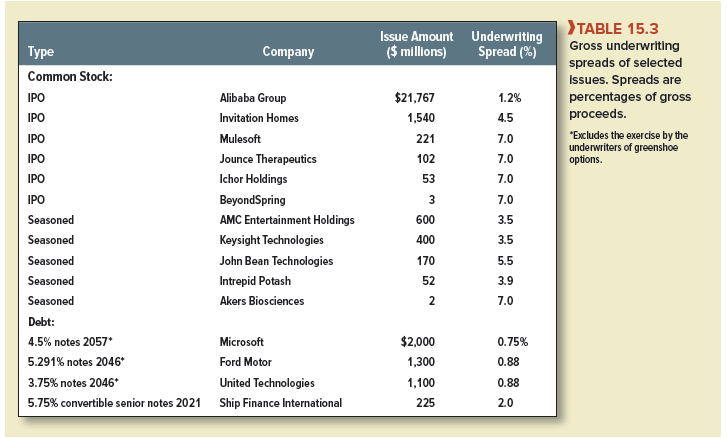

Table 15.3 lists underwriting spreads for a few recent issues. Notice that the underwriting spreads for debt securities are lower than for common stocks—less than 1% for many issues. Larger issues tend to have lower spreads than smaller issues. This may partly stem from the fact that there are fixed costs to selling securities, but large issues are generally made by large companies, which are better known and easier for the underwriter to monitor. So do not assume that a small company could make a jumbo issue at a negligible percentage spread.*

Figure 15.6 summarizes a study of total issue costs (spreads plus administrative costs) for several thousand issues between 2004 and 2008.

4. Market Reaction to Stock Issues

Economists who have studied seasoned issues of common stock have generally found that announcement of the issue results in a decline in the stock price of 2% to 4%.[6] While this may not sound overwhelming, the fall in market value is equivalent, on average, to nearly a third of the new money raised by the issue.

What’s going on here? One view is that the price of the stock is simply depressed by the prospect of the additional supply. On the other hand, there is little sign that the extent of the price fall increases with the size of the stock issue. There is an alternative explanation that seems to fit the facts better.

Suppose that the CFO of a restaurant chain is strongly optimistic about its prospects. From her point of view, the company’s stock price is too low. Yet the company wants to issue shares to finance expansion into the new state of Northern California.[7] What is she to do? All the choices have drawbacks. If the chain sells common stock, it will favor new investors at the expense of old shareholders. When investors come to share the CFO’s optimism, the share price will rise, and the bargain price to the new investors will be evident.

If the CFO could convince investors to accept her rosy view of the future, then new shares could be sold at a fair price. But this is not so easy. CEOs and CFOs always take care to sound upbeat, so just announcing “I’m optimistic” has little effect. But supplying detailed information about business plans and profit forecasts is costly and is also of great assistance to competitors.

The CFO could scale back or delay the expansion until the company’s stock price recovers. That too is costly, but it may be rational if the stock price is severely undervalued and a stock issue is the only source of financing.

If a CFO knows that the company’s stock is overvalued, the position is reversed. If the firm sells new shares at the high price, it will help existing shareholders at the expense of the new ones. Managers might be prepared to issue stock even if the new cash is just put in the bank.

Of course, investors are not stupid. They can predict that managers are more likely to issue stock when they think it is overvalued and that optimistic managers may cancel or defer issues. Therefore, when an equity issue is announced, they mark down the price of the stock accordingly. Thus the decline in the price of the stock at the time of the new issue may have nothing to do with the increased supply but simply with the information that the issue provides.[8]

Cornett and Tehranian devised a natural experiment that pretty much proves this point.[9] They examined a sample of stock issues by commercial banks. Some of these issues were necessary to meet capital standards set by banking regulators. The rest were ordinary, voluntary stock issues designed to raise money for various corporate purposes. The necessary issues caused a much smaller drop in stock prices than the voluntary ones, which makes perfect sense. If the issue is outside the manager’s discretion, announcement of the issue conveys no information about the manager’s view of the company’s prospects.[10]

Most financial economists now interpret the stock price drop on equity issue announcements as an information effect and not a result of the additional supply.[11] But what about an issue of preferred stock or debt? Are they equally likely to provide information to investors about company prospects? A pessimistic manager might be tempted to get a debt issue out before investors become aware of the bad news, but how much profit can you make for your shareholders by selling overpriced debt? Perhaps 1% or 2%. Investors know that a pessimistic manager has a much greater incentive to issue equity rather than preferred stock or debt. Therefore, when companies announce an issue of preferred or debt, there is a barely perceptible fall in the stock price.[12]

5. Rights Issues

Instead of making an issue of stock to investors at large, companies sometimes give their existing shareholders the right of first refusal. Such issues are known as privileged subscription, or rights, issues. In the United States, rights issues are largely confined to closed-end investment companies. However, in most countries outside the United States, rights issues are the most common method for seasoned equity issues. For example, rights offerings predominate in China, Germany, France, and Brazil.

We have already come across one example of a rights issue—the offer by the British bank HBOS, which ended up in the hands of its underwriters. Let us look more closely at another issue. In 2017, Deutsche Bank needed to raise €8 billion of equity to reduce its debt ratio. It did so by offering its existing shareholders the right to buy one new share for every two that they currently held. The new shares were priced at €11.65, about 35% below the preannouncement market price of €18.00.

Imagine that just before the rights issue you held two shares of Deutsche Bank valued at 2 x €18 = €36.00. Deutsche’s offer would give you the right to buy one new share for an additional outlay of €11.65. If you take up the offer, your holding increases to three shares, and the value increases by the amount of the extra cash to €36.00 + 11.65 = €47.65. Therefore, after the issue the value of each share is no longer €18.00 but a little lower at €47.65/3 = €15.88. This is termed the ex-rights price.

What is the value of the right to buy a new share for €11.65? The answer is €15.88 – €11.65 = €4.23.[14] An investor who could buy a share worth €15.88 for €11.65 would be willing to pay €4.23 for the privilege.[15]

It should be clear on reflection that Deutsche Bank could have raised the same amount of money on a variety of terms. For example, it could have offered shareholders the right to buy one new share at €5.825 for every share that they held. In this case, shareholders would buy twice as many shares at half the price. Our shareholder who initially held two shares would end up with four shares’ worth, in total, 2 x €18.00 + 2 x €5.825 = €47.65. The value of each share would be €47.65/4 = €11.91. Under this new arrangement, the ex-rights share price is lower, but you end up with four shares rather than three. The total value of your holding remains the same. Suppose that you wanted to sell your right to buy one new share for €5.825. Investors would be prepared to pay you €6.09 for this right. They would then pay €5.825 to Deutsche Bank and receive a share worth €11.91.

Deutsche’s shareholders were given about two weeks to decide whether they wished to take up the offer of new shares. If the stock price in the meantime fell below the issue price, shareholders would have no incentive to buy the new shares. For this reason, companies making a rights issue generally arrange for the underwriters to buy any unwanted stock. Underwriters are not often left holding the baby, but we saw earlier that in the case of the HBOS issue, they were left with a very large (and bouncing) baby.

Our example illustrates that as long as the company successfully sells the new shares, the issue price in a rights offering is irrelevant. That is not the case in a general cash offer. If the company sells stock to new shareholders for less than the market will bear, the buyer makes a profit at the expense of existing shareholders. As we noted earlier, general cash offers are typically sold at a small discount of about 3% on the previous day’s closing price, so underpricing is not a major worry. But since this cost can be avoided completely by using a rights issue, we are puzzled by the apparent preference of companies for general cash offers.

As I website owner I believe the subject material here is rattling wonderful, regards for your efforts.

I like this website very much, Its a real nice situation to read and obtain info .