The financial manager cannot freely choose the amount of investment in inventories or accounts receivable or the size of accounts payable; the amounts will depend in large part on the nature of the firm’s operations and the industry it is in.

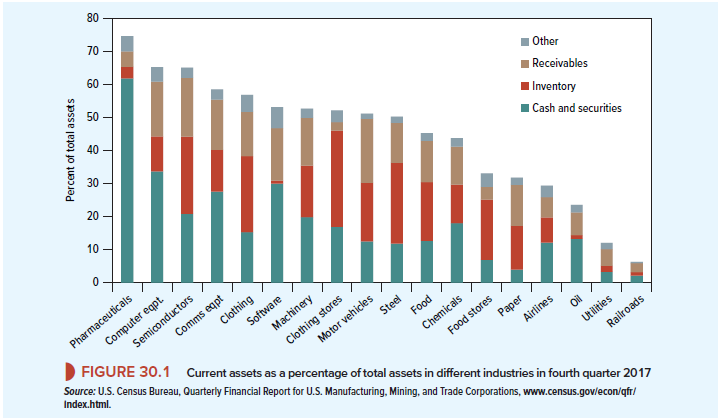

Figure 30.1 shows the relative importance of working capital in different industries. For example, current assets account for nearly 75% of total book assets of pharmaceutical companies but less than 10% of total book assets of railroads. For some industries, current assets means principally inventory; for others, it means accounts receivable or cash and securities. Retail firms hold large inventories. Receivables are relatively more important for auto producers. Cash and securities make up the bulk of current assets of computer and pharmaceutical companies.

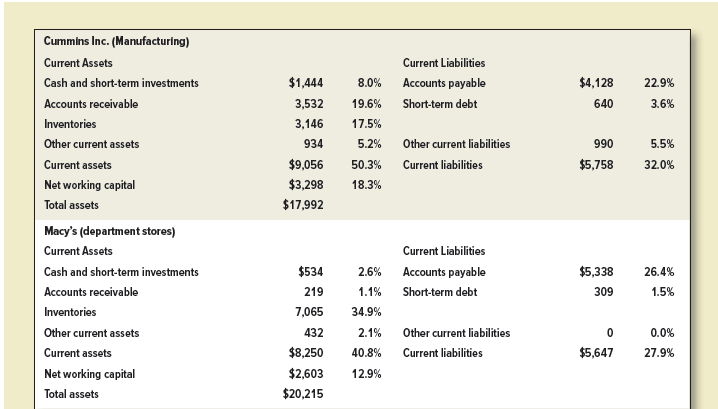

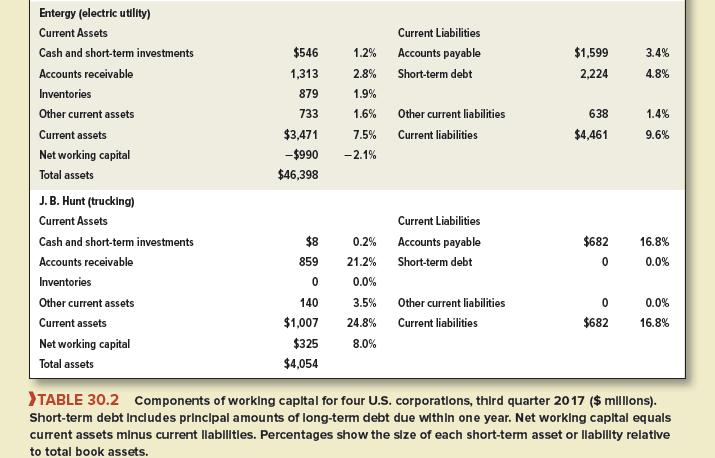

Table 30.2 presents working-capital balance sheets for four U.S. corporations: Cummins, a manufacturer, mostly of diesel engines; Macy’s department stores; electric utility Entergy; and trucking company J. B. Hunt.

The composition of Cummins’s working capital was not too different from the manufacturing aggregate in Table 30.1, although its net working capital was a larger fraction of net book assets. Cummins keeps extensive inventories of raw materials, work in progress, and finished goods awaiting sale. Its inventory of $3,146 million was 17.5% of total book assets. It carried about $3.5 billion in accounts receivable, but accounts payable were even larger at about $4.1 billion. Cummins was, in effect, financing its current assets partly with accounts payable because $4.1 billion due to its suppliers remained to be paid.

Macy’s current assets were dominated by inventory. Its shelves and warehouses were stocked with goods awaiting sale to retail customers. Other current assets were much less important. The most important current liability was accounts payable at about $5.3 billion. Like Cummins, Macy’s got short-term financing by deferring payments to suppliers.

Entergy’s current assets and liabilities were much smaller fractions of its total assets than for Cummins and Macy’s. Entergy’s inventories were small, which makes sense when you realize that its main product, electricity, cannot be stored and has to be produced at the instant it is consumed. Note also that Entergy’s current liabilities included about $2.2 billion of debt maturing in the coming year. Its current liabilities were larger than its current assets, so its net working capital was negative at slightly less than $1 billion. (There is nothing necessarily odd or dangerous about negative working capital. It happens frequently.

J.B. Hunt, a much smaller company than the other three in Table 30.2, carried no inventories at all. It transports goods; it does not buy and hold them in inventory for resale. Hunt’s working capital was dominated by large positions in receivables (21.2% of total assets) and payables (16.8% of total assets). It used no short-term debt financing.

We provide Table 30.2 just to alert you to the diversity that can be found in firms’ working- capital accounts and to illustrate some industry patterns. We now turn to the management of working capital, starting with inventory.

I do believe all of the ideas you have introduced on your post. They’re really convincing and will definitely work. Nonetheless, the posts are very quick for newbies. May just you please extend them a bit from subsequent time? Thanks for the post.