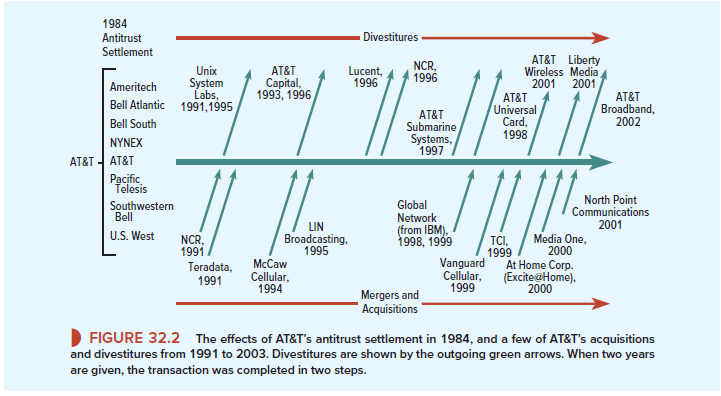

Figure 32.2 shows some of AT&T’s acquisitions and divestitures. Before 1984, AT&T controlled most of the local and virtually all of the long-distance telephone service in the United States. (Customers used to speak of the ubiquitous “Ma Bell.”) Then in 1984, the company accepted an antitrust settlement requiring local telephone services to be spun off to seven new, independent companies. AT&T was left with its long-distance business plus Bell Laboratories, Western Electric (telecommunications manufacturing), and various other assets. As the communications industry became increasingly competitive, AT&T acquired several other businesses, notably in computers, cellular telephone service, and cable television. Some of these acquisitions are shown as the green incoming arrows in Figure 32.2.

AT&T was an unusually active acquirer. It was a giant company trying to respond to rapidly changing technologies and markets. But AT&T was simultaneously divesting dozens of other businesses. For example, its credit card operations (the AT&T Universal Card) were sold to Citicorp. AT&T also created several new companies by spinning off parts of its business. For example, in 1996 it spun off Lucent (incorporating Bell Laboratories and Western Electric) and its computer business (NCR). Only six years earlier, AT&T had paid $7.5 billion to acquire NCR. These and several other important divestitures are shown as the green outgoing arrows in Figure 32.1.

Figure 32.2 is not the end of AT&T’s story. In 2004, AT&T was acquired by Cingular Wireless, which retained the AT&T name. In 2005, this company in turn merged with SBC

Communications Inc., a descendant of Southwestern Bell. By that point, there was not much left of the original AT&T, but the name survived. Recent events include AT&T’s acquisition of Direct TV for $48.5 billion in 2015 and its 2017 bid of $35 billion for Time Warner. The Time Warner bid was challenged by the U.S. Department of Justice, however. In early 2018, litigation was under way, and it is not clear whether the deal would go through.

In the market for corporate control, fusion—that is, mergers and acquisitions—gets most of the attention and publicity. But fission—the sale or distribution of assets or operating businesses—can be just as important, as the top half of Figure 32.2 illustrates. In many cases, businesses are sold in LBOs or MBOs. But other transactions are common, including spin-offs, carve-outs, divestitures, asset sales, and privatizations. We start with spin-offs.

1. Spin-Offs

A spin-off (or split-up) is a new, independent company created by detaching part of a parent company’s assets and operations. Shares in the new company are distributed to the parent company’s stockholders.[1] When e-Bay acquired PayPal in 2002, it stated that it was a natural extension of eBay’s trading platform. But the two companies proved to have very different cultures and were often in conflict. So in 2015, eBay announced that it intended to spin off PayPal in order “to capitalize on their respective growth opportunities in the rapidly changing global commerce and payments landscape.”

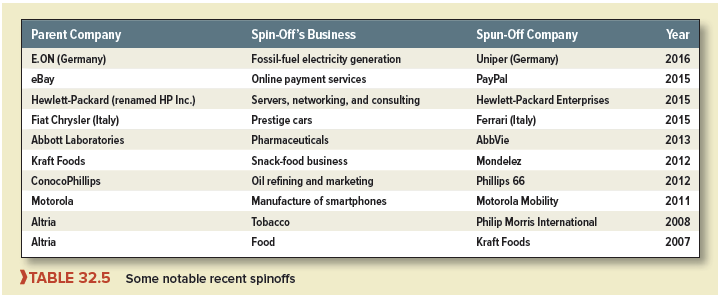

eBay was not alone in deciding to spin off. Table 32.5 lists a few other notable spinoffs of recent years.

Spin-offs widen investor choice by allowing them to invest in just one part of the business. More important, they can improve incentives for managers. Companies sometimes refer to divisions or lines of business as “poor fits.” By spinning these businesses off, management of the parent company can concentrate on its main activity. If the businesses are independent, it is easier to see the value and performance of each and to reward managers by giving them stock or stock options in their company. Also, spin-offs relieve investors of the worry that funds will be siphoned from one business to support unprofitable capital investments in another. For example, when Dow and DuPont announced their plan to merge and then split the proposed merged company into three separate businesses, the accompanying press release commented that these businesses:

. . . will include a leading global pure-play Agriculture company; a leading global pure-play Material Science company; and a leading technology and innovation-driven Specialty Products company. Each of the businesses will have clear focus, an appropriate capital structure, a distinct and compelling investment thesis, scale advantages, and focused investments in innovation to better deliver superior solutions and choices for customers. (DuPont press release, December 11, 2015)

Investors generally greet the announcement of a spin-off as good news.[2] Their enthusiasm appears to be justified, for spin-offs seem to bring about more efficient capital investment decisions by each company and improved operating performance.[3]

2. Carve-Outs

Carve-outs are similar to spin-offs, except that shares in the new company are not given to existing shareholders but are sold in a public offering. For example, when the German utility, E.ON decided to exit fossil-fuel electricity generation, it spun off this business into a separate company. Its rival, RWE, went in the opposite direction. It separated its wind and solar business into a new company, Innogy, and sold a 24% stake in the company by means of an IPO. This decision to carve out Innogy brought RWE €4.6 billion of much-needed cash, which it would not have received if it had spun-off the business.

Most carve-outs leave the parent with majority control of the subsidiary, usually about 80% ownership.[4] This may not reassure investors who are worried about a lack of focus or a poor fit, but it does allow the parent to set the manager’s compensation based on the performance of the subsidiary’s stock price. Sometimes companies carve out a small proportion of the shares to establish a market for the subsidiary’s stock and subsequently spin off the remainder of the shares. For example, in 2014 Fiat Chrysler announced plans to sell a 10% stake in Ferrari on the stock market and then to spin off the remaining shares to its stockholders. The nearby box describes how the computer company, Palm, was first carved and then spun.

Perhaps the most enthusiastic carver-outer of the 1980s and 1990s was Thermo Electron, with operations in health care, power generation equipment, instrumentation, environmental protection, and various other areas. By 1997, it had carved out stakes in seven publicly traded subsidiaries, which in turn had carved out 15 further public companies. The 15 were grandchildren of the ultimate parent, Thermo Electron. The company’s management reasoned that the carve-outs would give each company’s managers responsibility for their own decisions and expose their actions to the scrutiny of the capital markets. For a while, the strategy seemed to work, and Thermo Electron’s stock was a star performer. But the complex structure began to lead to inefficiencies, and in 2000, Thermo Electron went into reverse. It reacquired many of the subsidiaries that the company had carved out only a few years earlier, and it spun off several of its progeny, including Viasys Health Care and Kadant Inc., a manufacturer of paper-making and paper-recycling equipment. Then in November 2006, Thermo Electron merged with Fisher Scientific.

3. Asset Sales

The simplest way to divest an asset is to sell it. An asset sale or divestiture means sale of a part of one firm to another. This may consist of an odd factory or warehouse, but sometimes whole divisions are sold. Asset sales are another way of getting rid of “poor fits.” They may also be required by the FTC or Justice Department as a condition for approving a merger. Such sales are frequent. For example, one study found that more than 30% of assets acquired in a sample of hostile takeovers were subsequently sold.21

Maksimovic and Phillips examined a sample of about 50,000 U.S. manufacturing plants each year from 1974 to 1992. About 35,000 plants in the sample changed hands during that period. One-half of the ownership changes were the result of mergers or acquisitions of entire firms, but the other half resulted from asset sales—that is, sale of part or all of a division.22 Asset sales sometimes raise huge sums of money. For example, in 2017, the Anglo-Australian mining giant, BHP Billiton, announced that it was selling its U.S. shale oil assets for $10 billion. BHP was under pressure from activist investors to reduce its oil exposure.

Announcements of asset sales are good news for investors in the selling firm and on average the assets are employed more productively after the sale.[6] It appears that asset sales transfer business units to the companies that can manage them most effectively.

4. Privatization and Nationalization

A privatization is a sale of a government-owned company to private investors. In recent years, almost every government in the world seems to have a privatization program. Here are some examples of recent privatization news:

- Japan sells the West Japan Railway Company (March 2004).

- Germany privatizes Postbank, the country’s largest retail bank (June 2004).

- France sells 30% of EDF (Electricite de France; December 2005).

- China sells Industrial and Commercial Bank of China (October 2006).

- Poland sells Tauron Polska Energia (March 2011).

- K. sells Royal Mail (October 2013).

- Greece sells 67% stake in port of Piraeus (April 2016).

- Brazil decides to privatize its biggest power utility (August 2017).

Most privatizations are more like carve-outs than spin-offs because shares are sold for cash rather than distributed to the ultimate “shareholders”—that is, the citizens of the selling country. But several former communist countries, including Russia, Poland, and the Czech Republic, privatized by means of vouchers distributed to citizens. The vouchers could be used to bid for shares in the companies that were being privatized. Thus, the companies were not sold for cash, but for vouchers.[7]

Privatizations have raised enormous sums for governments. China raised $22 billion from the privatization of the Industrial and Commercial Bank of China. The Japanese government’s successive sales of its holding of NTT (Nippon Telegraph and Telephone) brought in $100 billion.

In many cases, governments have retained a stake in the privatized company or have taken stakes in companies that have hitherto been entirely privately owned. The idea is that the government can represent the wider interests of society and help to safeguard jobs. But you can see the dangers that may arise when the company is subject to political interference.

The motives for privatization seem to boil down to the following three points:

- Increased efficiency. Through privatization, the enterprise is exposed to the discipline of competition and insulated from political influence on investment and operating decisions. Managers and employees can be given stronger incentives to cut costs and add value.

- Share ownership. Privatizations encourage share ownership. Many privatizations give special terms or allotments to employees or small investors.

- Revenue for the government. Last but not least.

There were fears that privatizations would lead to massive layoffs and unemployment, but that does not appear to be the case. While it is true that privatized companies operate more efficiently and thus reduce employment, they also grow faster as privatized companies, which increases employment. In many cases the net effect on employment has been positive.

On other dimensions, the impact of privatization is almost always positive. A review of research on the issue concludes that the firms “almost always become more efficient, more profitable, . . . financially healthier and increase their capital investment spending.”25

The process of privatization is not a one-way street. It can sometimes go into reverse, and publicly owned firms may be taken over by the government. For example, as part of his aim to construct a socialist republic in Venezuela, Hugo Chavez nationalized firms in the banking, oil, power, telecom, steel, and cement sectors.

In some other countries, temporary nationalization has been a pragmatic last resort for governments rather than part of a long-term strategy. For example, in 2008, the U.S. government took control of the giant mortgage companies Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac when they were threatened with bankruptcy.26 In 2012, the Japanese government agreed to provide 1 trillion yen in return for a majority holding in Tepco, operator of the stricken Fukushima nuclear plant.

24 Jun 2021

24 Jun 2021

25 Jun 2021

24 Jun 2021

24 Jun 2021

25 Jun 2021