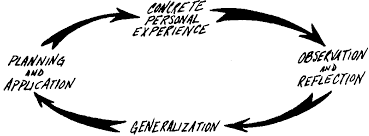

Interview because I am interested in other people’s stories. Most simply put, stories are a way of knowing. The root of the word story is the Greek word histor, which means one who is “wise” and “learned” (Watkins, 1985, p. 74). Telling stories is essentially a meaning-making process. When people tell stories, they select details of their experience from their stream of consciousness. Every whole story, Aristotle tells us, has a beginning, a middle, and an end (Butcher, 1902). In order to give the details of their experience a beginning, middle, and end, people must reflect on their experience. It is this process of selecting constitutive details of experience, reflecting on them, giving them order, and thereby making sense of them that makes telling stories a meaning-making experience. (See Schutz, 1967, p. 12 and p. 50, for aspects of the relationship between reflection and meaning making.)

Every word that people use in telling their stories is a microcosm of their consciousness (Vygotsky, 1987, pp. 236-237). Individuals’ consciousness gives access to the most complicated social and educational issues, because social and educational issues are abstractions based on the concrete experience of people. W. E. B. Du Bois knew this when he wrote, “I seem to see a way of elucidating the inner meaning of life and significance of that race problem by explaining it in terms of the one human life that I know best” (Wideman, 1990, p. xiv).

Although anthropologists have long been interested in people’s stories as a way of understanding their culture, such an approach to research in education has not been widely accepted. For many years those who were trying to make education a respected academic discipline in universities argued that education could be a science (Bailyn, 1963). They urged their colleagues in education to adapt research models patterned after those in the natural and physical sciences.

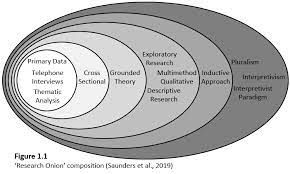

In the 1970s a reaction to the dominance of experimental, quantitative, and behaviorist research in education began to develop (Gage, 1989). The critique had its own energy and was also a reflection of the era’s more general resistance to received authority (Gitlin, 1987, esp.chap. 4). Researchers in education split into two, almost warring, camps: quantitative and qualitative.

It is interesting to note that the debate between the two camps got especially fierce and the polemics more extreme when the economics of higher education took a downturn in the mid-1970s and early 1980s (Gage, 1989). But the political battles were informed by real epistemological differences. The underlying assumptions about the nature of reality, the relationship of the knower and the known, the possibility of objectivity, the possibility of generalization, inherent in each approach are different and to a considerable degree contradictory. To begin to understand these basic differences in assumptions, I urge you to read James (1947), Lincoln and Guba (1985, chap. 1), Mannheim (1975), and Polanyi (1958).

For those interested in interviewing as a method of research, perhaps the most telling argument between the two camps centers on the significance of language to inquiry with human beings. Bertaux (1981) has argued that those who urge educational researchers to imitate the natural sciences seem to ignore one basic difference between the subjects of inquiry in the natural sciences and those in the social sciences: The subjects of inquiry in the social sciences can talk and think. Unlike a planet, or a chemical, or a lever, “If given a chance to talk freely, people appear to know a lot about what is going on” (p. 39).

At the very heart of what it means to be human is the ability of people to symbolize their experience through language. To understand human behavior means to understand the use of language (Heron, 1981). Heron points out that the original and archetypal paradigm of human inquiry is two persons talking and asking questions of each other. He says:

The use of language, itself, . . . contains within it the paradigm of cooperative inquiry; and since language is the primary tool whose use enables human construing and intending to occur, it is difficult to see how there can be any more fundamental mode of inquiry for human beings into the human condition. (p. 26)

Interviewing, then, is a basic mode of inquiry. Recounting narratives of experience has been the major way throughout recorded history that humans have made sense of their experience. To those who would ask, however, “Is telling stories science?” Peter Reason (1981) would respond,

The best stories are those which stir people’s minds, hearts, and souls and by so doing give them new insights into themselves, their problems and their human condition. The challenge is to develop a human science that can more fully serve this aim. The question, then, is not “Is story telling science?” but “Can science learn to tell good stories?” (p. 50)

1. THE PURPOSE OF INTERVIEWING

The purpose of in-depth interviewing is not to get answers to questions, nor to test hypotheses, and not to “evaluate” as the term is normally used. (See Patton, 1989, for an exception.) At the root of in-depth interviewing is an interest in understanding the lived experience of other people and the meaning they make of that experience. (For a deeply thoughtful elaboration of a phenomenological approach to research, see Van Manen, 1990, from whom the notion of exploring “lived” experience mentioned throughout this text is taken.)

Being interested in others is the key to some of the basic assumptions underlying interviewing technique. It requires that we interviewers keep our egos in check. It requires that we realize we are not the center of the world. It demands that our actions as interviewers indicate that others’ stories are important.

At the heart of interviewing research is an interest in other individuals’ stories because they are of worth. That is why people whom we interview are hard to code with numbers, and why finding pseudonyms for partici- pants1 is a complex and sensitive task. (See Kvale, 1996, pp. 259-260, for a discussion of the dangers of the careless use of pseudonyms.) Their stories defy the anonymity of a number and almost that of a pseudonym. To hold the conviction that we know enough already and don’t need to know others’ stories is not only anti-intellectual; it also leaves us, at one extreme, prone to violence to others (Todorov, 1984).

Schutz (1967, chap. 3) offers us guidance. First of all, he says that it is never possible to understand another perfectly, because to do so would mean that we had entered into the other’s stream of consciousness and experienced what he or she had. If we could do that, we would be that other person.

Recognizing the limits on our understanding of others, we can still strive to comprehend them by understanding their actions. Schutz gives the example of walking in the woods and seeing a man chopping wood. The observer can watch this behavior and have an “observational understanding” of the woodchopper. But what the observer understands as a result of this observation may not be at all consistent with how the wood- chopper views his own behavior. (In analogous terms, think of the problem of observing students or teachers.) To understand the woodchopper’s behavior, the observer would have to gain access to the woodchopper’s “subjective understanding,” that is, know what meaning he himself made out of his chopping wood. The way to meaning, Schutz says, is to be able to put behavior in context. Was the woodchopper chopping wood to supply a logger, heat his home, or get in shape? (For Schutz’s complete and detailed explication of this argument, see esp. chaps. 1-3. For a thoughtful secondary source on research methodology based on phenomenology, for which Schutz is one primary resource, see Moustakas, 1994.)

Interviewing provides access to the context of people’s behavior and thereby provides a way for researchers to understand the meaning of that behavior. A basic assumption in in-depth interviewing research is that the meaning people make of their experience affects the way they carry out that experience (Blumer, 1969, p. 2). To observe a teacher, student, principal, or counselor provides access to their behavior. Interviewing allows us to put behavior in context and provides access to understanding their action. The best article I have read on the importance of context for meaning is Elliot Mishler’s (1979) “Meaning in Context: Is There Any Other Kind?” the theme of which was later expanded into his book, Research Interviewing: Context and Narrative (1986). Ian Dey (1993) also stresses the significance of context in the interpretation of data in his useful book on qualitative data analysis.

2. INTERVIEWING: “THE” METHOD OR “A” METHOD?

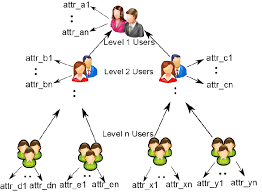

The primary way a researcher can investigate an educational organization, institution, or process is through the experience of the individual people, the “others” who make up the organization or carry out the process. Social abstractions like “education” are best understood through the experiences of the individuals whose work and lives are the stuff upon which the abstractions are built (Ferrarotti, 1981). So much research is done on schooling in the United States; yet so little of it is based on studies involving the perspective of the students, teachers, administrators, counselors, special subject teachers, nurses, psychologists, cafeteria workers, secretaries, school crossing guards, bus drivers, parents, and school committee members, whose individual and collective experience constitutes schooling.

A researcher can approach the experience of people in contemporary organizations through examining personal and institutional documents, through observation, through exploring history, through experimentation, through questionnaires and surveys, and through a review of existing literature. If the researcher’s goal, however, is to understand the meaning people involved in education make of their experience, then interviewing provides a necessary, if not always completely sufficient, avenue of inquiry.

An educational researcher might suggest that the other avenues of inquiry listed above offer access to people’s experience and the meaning they make of it as effectively as and at less cost than does interviewing. I would not argue that there is one right way, or that one way is better than another. Howard Becker, Blanche Geer, and Martin Trow carried on an argument in 1957 that still gains attention in the literature because, among other reasons, Becker and Geer seemed to be arguing that participant observation was the single and best way to gather data about people in society. Trow took exception and argued back that for some purposes interviewing is far superior (Becker & Geer, 1957; Trow, 1957).

The adequacy of a research method depends on the purpose of the research and the questions being asked (Locke, 1989). If a researcher is asking a question such as, “How do people behave in this classroom?” then participant observation might be the best method of inquiry. If the researcher is asking, “How does the placement of students in a level of the tracking system correlate with social class and race?” then a survey may be the best approach. If the researcher is wondering whether a new curriculum affects students’ achievements on standardized tests, then a quasi-experimental, controlled study might be most effective. Research interests don’t always or often come out so neatly. In many cases, research interests have many levels, and as a result multiple methods may be appropriate. If the researcher is interested, however, in what it is like for students to be in the classroom, what their experience is, and what meaning they make out of that experience—if the interest is in what Schutz (1967) calls their “subjective understanding”—then it seems to me that interviewing, in most cases, may be the best avenue of inquiry.

I say “in most cases,” because below a certain age, interviewing children may not work. I would not rule out the possibility, however, of sitting down with even very young children to ask them about their experience. Carlisle (1988) interviewed first-grade students about their responses to literature. She found that although she had to shorten the length of time that she interviewed students, she was successful at exploring with first graders their experience with books.

3. WHY NOT INTERVIEW?

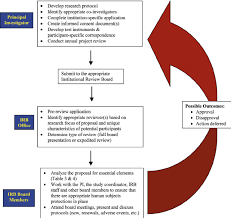

Interviewing research takes a great deal of time and, sometimes, money. The researcher has to conceptualize the project, establish access and make contact with participants, interview them, transcribe the data, and then work with the material and share what he or she has learned. Sometimes I sense that a new researcher is choosing one method because he or she thinks it will be easier than another. Any method of inquiry worth anything takes time, thoughtfulness, energy, and money. But interviewing is especially labor intensive. If the researcher does not have the money or the support to hire secretarial help to transcribe tapes, it is his or her labor that is at stake. (See Chapter 8.)

Interviewing requires that researchers establish access to, and make contact with, potential participants whom they have never met. If they are unduly shy about themselves or hate to make phone calls, the process of getting started can be daunting. On the other hand, overcoming shyness, taking the initiative, establishing contact, and scheduling and completing the first set of interviews can be a very satisfying accomplishment.

My sense is that graduate programs today in general, and the one in which I teach in particular, are much more individualized and less monolithic than I thought them to be when I was a doctoral candidate. Students have a choice of the type of research methodology they wish to pursue. But in some graduate programs there may be a cost to pay for that freedom: Those interested in qualitative research may not be required to learn the tenets of what is called “quantitative” research. As a result, some students tend not to understand the history of the method they are using or the critique of positivism and experimentalism out of which some approaches to qualitative research in education grew. (For those interested in learning that critique as an underpinning for their work, as a start see Johnson, 1975; Lincoln & Guba, 1985.)

Graduate candidates must understand the so-called paradigm wars (Gage, 1989) that took place in the 1970s and 1980s and are still being waged in the 2000s (Shavelson & Towne, 2002). By not being aware of the history of the battle and the fields upon which it has been fought, students may not understand their own position in it and the potential implications for their career as it continues. If doctoral candidates choose to use interviewing as a research methodology for their dissertation or other early research, they should know that their choice to do qualitative research has not been the dominant one in the history of educational research. Although qualitative research has gained ground in the last 30 years, professional organizations, some journals in education, and personnel committees on which senior faculty tend to sit, are often dominated by those who have a predilection for quantitative research. Furthermore, the federal government issued an additional challenge to qualitative researchers when it enacted legislation that guides federal funding agencies to award grants to researchers whose methodologies adhere to “scientific” standards. (See the definition of “scientific” in section 102,18 of the Education Sciences Reform Act of 2002.) In some arenas, doctoral candidates choosing to do qualitative rather than quantitative research may have to fight a stiffer battle to establish themselves as credible. They may also have to be comfortable with being outside the center of the conventional educational establishments. They will have to learn to search out funding agencies, journals, and publishers open to qualitative approaches. (For a discussion of some of these issues, see Mishler, 1986, esp. pp. 141-143; Wolcott, 1994, pp. 417-422.)

Although the choice of a research method ideally is determined by what one is trying to learn, those coming into the field of educational research must know that some researchers and scholars see the choice as a political and moral one. (See Bertaux, 1981; Fay, 1987; Gage, 1989; Lather, 1986a, 1986b; Popkowitz, 1984.) Those who espouse qualitative research often take the high moral road. Among other criticism, they decry the way quantitative research turns human beings into numbers.

But, there are equally serious moral issues involved in qualitative research. As I read Todorov’s (1984) The Conquest of America, I began to think of interviewing as a process that turns others into subjects so that their words can be appropriated for the benefit of the researcher. Daphne Patai (1987) raises a similar issue when she points out that the Brazilian women she interviewed seemed to enjoy the activity, but she was deeply troubled by the possibility that she was exploiting them for her scholarship.

Interviewing as exploitation is a serious concern and provides a contradiction and a tension within my work that I have not fully resolved. Part of the issue is, as Patai recognizes, an economic one. Steps can be taken to assure that participants receive an equitable share of whatever financial profits ensue from their participation in research. But, at a deeper level, there is a more basic question of research for whom, by whom, and to what end. Research is often done by people in relative positions of power in the guise of reform. All too often the only interests served are those of the researcher’s personal advancement. It is a constant struggle to make the research process equitable, especially in the United States where a good deal of our social structure is inequitable.

Main contentsSee more from basic to advanced

Source: Seidman Irving (2006), Interviewing As Qualitative Research: A Guide for Researchers in Education And the Social Sciences, Teachers College Press; 3rd edition.

12 Aug 2021

12 Aug 2021

12 Aug 2021

12 Aug 2021

12 Aug 2021

12 Aug 2021